Being Jewish

Forging a New Vision of American Judaism and American Zionism

Adapted excerpt from For Such a Time as This: On Being Jewish Today by Rabbi Elliot Cosgrove:

History will remember October 7, 2023, as an inflection point. There will be a story of all that came before and all that came afterward.

The “post” of our post-October 7 reality continues to evolve. Our Israeli brothers and sisters struggle with how to prosecute war, secure peace, maintain the country’s international standing and address its internal divisions. So, too, American Jews face both new questions and old ones asked with new urgency. Questions related to our hyphenated identities, the invisible string that ties us to Israel, our sense of home in America. We told ourselves that we were different from the Jews of postwar Europe or ancient Egypt or Persia. Now, after October 7, we wonder if we have become but one more case study in the annals of the world’s most ancient hatred. As we move forward, what stays and what goes? Is it time for a new script or time to double down on the old one?

In a world with no easy answers, I find both wisdom and comfort in a rabbinic midrash told of the darkest moments of biblical Israel’s desert sojourn—the incident of the Golden Calf.

When Moses ascended Mount Sinai to receive the Ten Commandments, he stayed atop the mountain for 40 days and 40 nights. The newly emancipated children of Israel grew restless waiting for their leader to return and, needing something to worship, they built the Golden Calf.

When Moses descended the mountain and saw his people engaged in idolatry, he threw the tablets to the ground, shattering them. We know that a second set of tablets was constructed and placed in the Ark of the Covenant to accompany the Israelites on their journey forward. But what, the rabbis of the Talmud ask, happened to the shattered fragments of the first set? Were the shards left on top of the mountain? Perhaps, like the Golden Calf itself, they were destroyed—fragments of a painful memory better left in the past? Some things are best left behind.

The rabbis suggest otherwise. “Luchot ve’shivrey luchot munachim be’aron,” states the Talmud. “The tablets and the broken tablets side-by-side in the Ark together” (Berachot 8b). The image is powerful—both the broken and the whole lead Israel on the journey forward. We pick up the pieces. We remember the hurt, hold on to the pain and nevertheless put one foot ahead of the other. Nothing is left behind. The forward momentum of our people actually depends on carrying both realities with us—shattered and whole, on our way to the Promised Land.

I believe the task of American Jewry is to find the means to bring both sets of tablets along on our journey. We can integrate the wisdom of everything that came before October 7, the newly learned wisdom of our post-October 7 reality, and most of all, the fact that the truth is not present exclusively in one or the other but in the integration of the two. A new vision for American Judaism and American Zionism, the shattered truths we held sacred and a bold new vision that embraces the complexity, paradoxes and even the internal contradictions of our time. Our engagement with Israel, our engagement with tradition and, perhaps most of all, our engagement with one another will lend us support.

So what should American Zionism look like, moving forward?

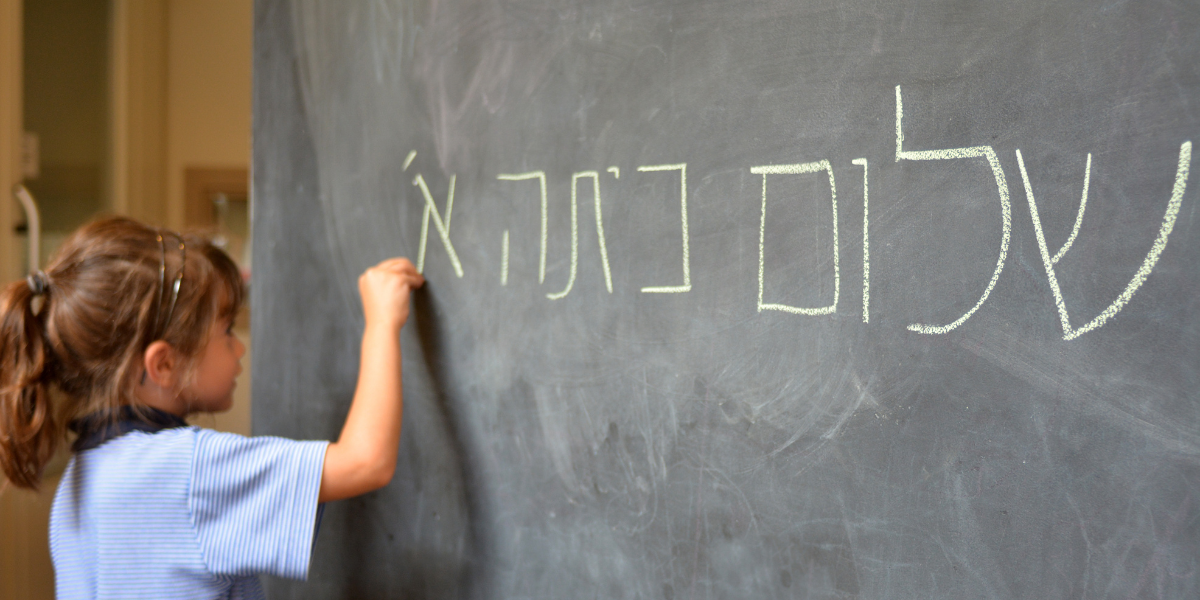

First and foremost, we need an American Zionism that begins with love for the Jewish people and teaches our children and grandchildren the story of our exile, the pitfalls of powerlessness, the dreams of every wave and every stage of our national longings and our right to the land. American Jewry has become woefully ahistorical. We need a “Marshall Plan” to rebuild our deficit of memory; you can’t love a country that you know only by way of social media. We need formal, informal and, most important, experiential curricula; our children should be in dialogue with Israeli children by way of technology, exchange programs, sister congregations, any means available. Israel educators, “reverse” Birthright programs that bring Israelis into contact with American Jews, and a redoubling of efforts on teaching the Hebrew language—perhaps our people’s most effective bridge to one another, to our past and to our future.

Next, we need an American Zionism with a dose of humility. The Middle East is not New York City, and the democratically elected government of Israel has every right to make decisions in the best interests of Israel, even when these decisions run contrary to our sensibilities. Israel lives in a very rough neighborhood, and the community of nations holds Israel to a nasty double standard that is often, but not always, laced with explicit or implicit antisemitism. Lest we forget, Abraham was called Ha-Ivri, meaning “the other,” because he stood alone when the rest of the world stood on the other side. There is nothing wrong, in fact there is everything right, about standing at Israel’s side, even when, and sometimes especially when, it makes decisions we ourselves would not make. In school, on campus and on Capitol Hill, the coming generation of American Zionists must be given tools that will help them be resilient, self-confident and adroit defenders of the real, not the imagined, Jewish state.

But for the next chapter of American Zionism to ring true and stand the test of time, we must also be willing and able to integrate the universal and prophetic dimension of American Jewry. If the project of Zionism, as Martin Buber once reflected, is the Jewish use of power tempered by morality, it is a project that sometimes Israel gets right and sometimes gets wrong. If the dream of Israel is to serve as a homeland for all Jews and all forms of Jewish expression, we must confront the bitter truth that this dream is now threatened by the government of the Jewish state. There is bitter irony in the realization that, because of the stranglehold of the ultra-Orthodox Chief Rabbinate, many Jews cannot practice their Judaism freely in the Jewish state.

As evidenced by political infighting and the judicial reform protests prior to October 7, Israel faces this challenge: how to remain a liberal democracy without giving short shrift to security concerns. There is nothing wrong with helping, chiding or goading Israel toward achieving this complicated goal, as long as that nudging comes from a place of abiding concern for Israel’s safety and security. The “sane center” must not let those who have embraced the ideological and philanthropic extremes define the field of play and terms of debate. We can support religious pluralism, efforts to achieve Arab-Jewish coexistence and dialogue and constructive steps toward creating a two-state solution.

Finally, we need to understand that the new American Zionism is not a substitute for American Judaism. For far too many Jews, support for Israel became a vicarious faith, a civil religion masking the inadequacies of our actual religion. The only way Israel will learn from, listen to or care about American Jews is if we show ourselves to be living energetic Jewish lives. To be good Zionists, we must be better Jews. A robust American Jewish identity can weather policy differences with this or that Israeli government and withstand the indignity of being a punching bag for a campus culture run amok—something a paper-thin Jewish identity cannot do.

Build up your own Jewish identity and that of your children and grandchildren and do everything in your power to support individuals and institutions committed to nurturing and sustaining the global Jewish community.

Taking agency in our Jewish lives—this is the North Star of my vocation as a rabbi. Not everyone will choose to be a rabbi. But the choice to take agency is something we all must face—asking whether to lean into the opportunity and blessing of being connected to a tradition, people and faith.

The future of American Zionism is contingent on the future of American Judaism—not the other way around. American Jewry must redouble its investment in Jewish life and living. As invested as we are in Israel, for the sake of our Jewish and Zionist future we must prioritize efforts to cultivate rich Jewish identities: synagogues, schools and Jewish summer camps filled with Jews living intentionally and joyfully, capable of producing the next generation of American Judaism and training the next generation of rabbis, cantors, Jewish educators and professionals.

An American Zionism filled with love, humility and intentional Jewish living will not be monolithic. It must be sufficiently supple and capacious to house many voices. Can an American Jew emphatically support Israel’s right to self-defense and self-determination and yet be critical of the Israeli government? Can that person be vigilant on Israel’s behalf and empathetic on the Palestinians’ behalf? For far too long, American Jewry has been fed a series of binaries, a choice between one or the other only.

Such a narrow range of options must be called out as false; in a new American Zionism, it must be rejected outright. We who love Israel can be both critical and supportive of Israel. The hundreds of thousands of Israelis at the forefront of the protest against judicial reform became Israel’s most capable defenders following October 7. So, too, those American Jews who spoke out against Israel’s government and on behalf of Israeli democracy prior to October 7, myself included. We have now pivoted and are unflinching in our support for Israel. In American Jewry’s support of a Jewish and democratic State of Israel, criticism and love are not in opposition—they are two sides of the same coin.

As American Jews witness the precipitous rise of anti-Israel sentiment and antisemitism today, should we be self-reflective or reach out? The answer is not one or the other—it is both. As we find ourselves at odds with many educational, cultural and political institutions—should we recuse ourselves or rescue these institutions from within? The answer is not one or the other—it is both. Must American Jewry steadfastly advocate for Israel’s right to self-defense or express empathy for Palestinians, who are pawns in the inhuman strategy of Hamas? The answer is not one or the other—it is both. As we face a cross-generational schism concerning our obligations to Israel, American Jewry must construct a big tent capable of housing a plurality of voices. At all costs, our culture of debate must avoid the enemy within—baseless hatred, sinat hinam—in the form of ad hominem attacks intended to “cancel” others rather than focus on issues.

Not just the competing visions, but the manner by which those visions are negotiated—that is the task Israel faces, and American Jews have a critical role to play in shaping what will be. It is not easy to balance the binaries, especially when the stakes are high—but as a people, binaries are at the essence of who we are.

The 20th century scholar Simon Rawidowicz wrote a now-famous essay titled “Israel: The Ever-Dying People.” In it, he explains the belief held in every age and stage of Jewish existence: Surely this one was to be the last one. From Abraham to Rabbi Akiva, from Shushan to the former Soviet Union—whether because of persecution, dispersion or the forces of assimilation, we are a people marked by the perennial belief that we are at risk of extinction. Then, of course, the next generation arrives—utterly convinced of the same idea. Rawidowicz argues that our multimillennial against-the-odds survival as a people is not based on anxiety about this notion; rather, every generation has leveraged this mentality to respond and act, leading us from strength to strength and building bridges from one Jewish generation to the next.

And now our generation has its opportunity to respond to this idea, our people’s recurring cri de coeur, concerning its survival.

As a people, our faith is directed not just toward God or one another. Our faith is a combination of courage and hope wrought from within, which impels us to work feverishly toward a bright Jewish future. We are not unaware of the hurdles we face or the possibility of failure. We carry both sets of tablets with us. That which is broken and that which is whole lead us on our journey to the Promised Land, forging for ourselves and others a better life and a better world.

Rabbi Elliot Cosgrove, a leading voice of American Jewry, is senior rabbi of Park Avenue Synagogue in New York City. Adapted excerpt from For Such a Time as This: On Being Jewish Today by Elliot Cosgrove (Harvest; September 24, 2024). © 2024 by Elliot Cosgrove, used with permission from the publisher.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Lynn Glassman says

Thank you, Elliot Cosgrove, for stating our continue-to-survive game plan for, yet, another generation. It’s doable; it makes sense; we are doing it!

Am Israel Chai