Books

Books on Motherhood in All Its Permutations

Since I became pregnant with my daughter over 30 years ago, I have been something of a 24-hour sentry. I can’t seem to break the impulse that left me on duty as a parent morning, noon and night, seven days a week. The psychology books have a descriptor for me—I am hypervigilant.

When my girl was a baby, I stood over her to listen to her sweet breathing almost every day. My hypervigilance later extended to her test-taking in college, and beyond. In twisted logic that only made sense to me, l had test anxiety so that she would not.

My second child, a son, was born premature and had colic daily. He began crying at 9 every evening and did not stop until 5 in the morning. During the day, he catnapped in 30-minute segments. My husband and I were so exhausted that neither of us dared drive after sunset.

My son’s screaming went on for six months—until, one day, it suddenly stopped. I was skeptical. That first quiet night, I crept into his room and saw that he was sleeping soundly. My premature son had begun to catch up to his age. Milestones and sleep were in sight. My sanity was just around the corner.

But for his first six months, I was exhausted and angry, caught between hypervigilance and the inability to soothe my son by rocking him or breastfeeding.

Margo Lowy, author of Maternal Ambivalence: The Loving Moments & Bitter Truths of Motherhood, might have described me as having maternal ambivalence at its most extreme. In her book, she distills maternal ambivalence as a positive, calling it “the essence of mothering.” Lowy adds that “the variations and shades that exist in the mother’s loving emotions, such as feelings of enjoyment, compassion, delight, and in her darker emotions, including fear, resentment, shame, guilt, despair, and abhorrence. All these sensations must be named, claimed, and given breathing space.”

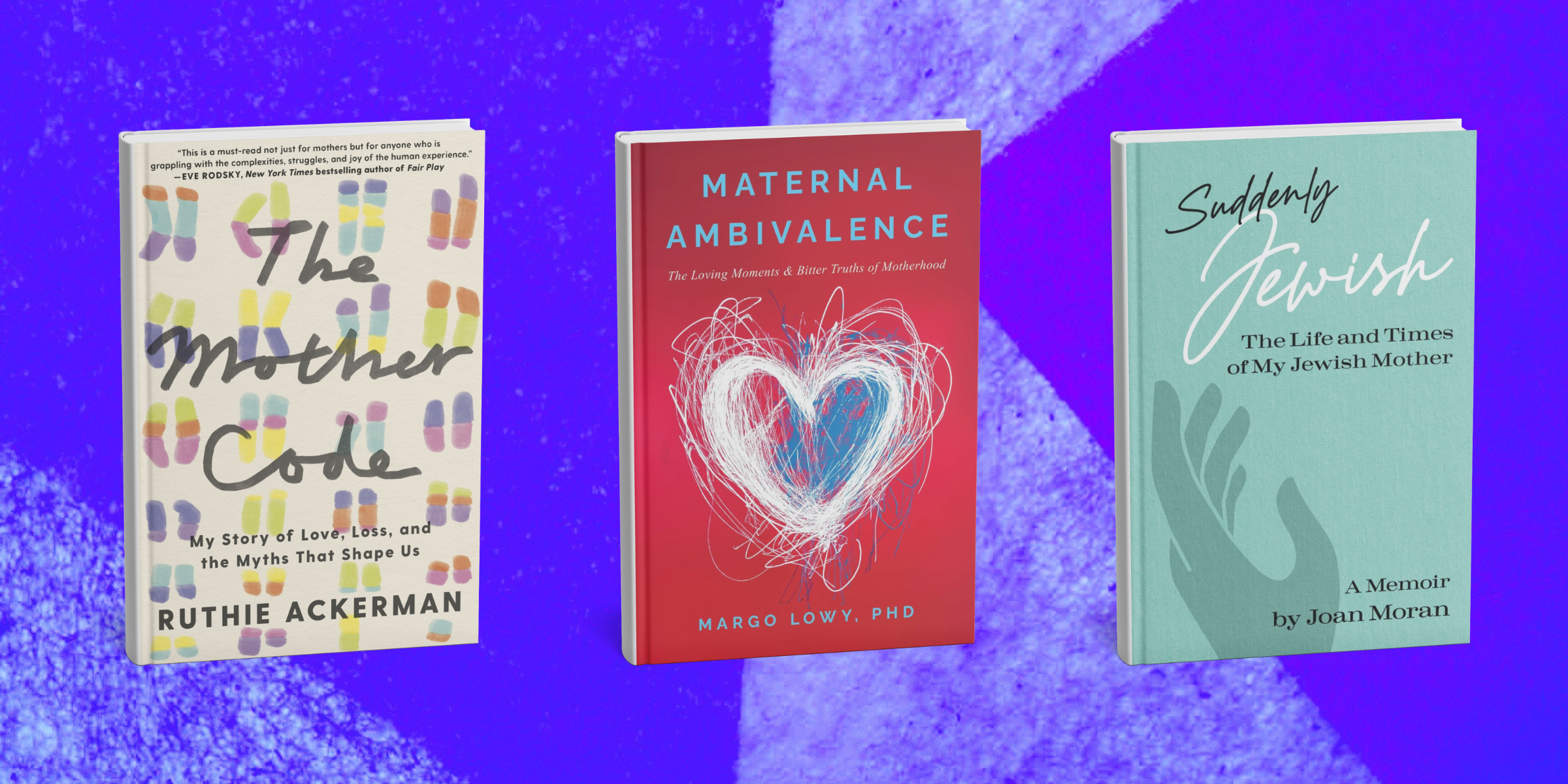

Lowy’s book is one of several recent titles on motherhood by Jewish women that name and claim different ways of being a mom. These include Suddenly Jewish: The Life and Times of My Jewish Mother by Joan Moran and The Mother Code: My Story of Loss and Love, and the Myths that Shape Us by Ruthie Ackerman. (See also the review of Mothers and Other Fictional Characters: A Memoir in Essays by Nicole Graev.)

Moran’s title is a family history and Ackerman’s a memoir, while Lowy’s is a sociological exploration. Yet each gives space for the varied feelings, the contradictions and complications around motherhood.

Lowy, a psychotherapist and social worker who specializes in issues around motherhood and infertility, claims that the idea of the “good enough mother,” a term coined by 1950s British psychologist and pediatrician Dr. Donald Winnicott, is a perfect description of ambivalent motherhood.

In her exploration of the various emotions around that ambivalence, Lowy differentiates between feelings of guilt and shame, using case studies from her own practice as well as her experience as a parent of three children. She concludes that shame is more harmful to a mother. “It’s a mother’s sense,” she writes, “that there’s something wrong with her.”

Moran’s Suddenly Jewish, in contrast, presents three generations of women in a narrative that outlines the various roles of a Jewish mom.

She opens her book with a family saga set in 1920s New York City, when the author’s maternal grandmother, Rose Lanch, is secretly lighting Shabbat candles to avoid the wrath of her intolerant husband, Jake. A union man leading the Garment Workers Union branches in New York City and in San Francisco, Jake is a communist who abhors anything with a whiff of religion. Rose and he eventually settle in San Francisco, where they come to lead separate lives.

Rose holds on to her Judaism yet is unable to pass on her belief to her daughter Esther, the author’s mother. Esther is an adamant atheist like her father, and her first move toward independence as a teenager is to change her name to Estelle. She even sheds her Jewish identity when looking for work, writing that she is Protestant on a job application.

However, Moran complicates the Jewish mother role in thought-provoking ways. She describes how Estelle was thrust into motherhood even before she officially became a mother, partly helping to support her family with the superb tailoring skills she learns from her father and caring for her younger sister, Mildred. In one emotionally high-stakes incident, Estelle shepherds Mildred through a back-alley abortion.

Estelle is strong, bright and ambitious, finding work despite the antisemitism underlaying the culture of San Francisco of the early 20th century. She falls in love with Daniel, an observant Jewish boy who works at a local deli, but cannot picture marrying him and leading an observant life. Moran admirably perceives Estelle as a cultural Jew, a term not in use in the 1920s. Ultimately, Estelle marries John Moran, an Irish Catholic man whose antisemitic mother cannot tolerate her new daughter-in-law.

Despite her feelings about religion, Estelle allows John to raise their children Catholic. Growing up, Moran went to weekly Sunday mass with her father. Her mother only disclosed her own Jewish background when Moran was a young woman. Yet the daughter feels something unambiguously Jewish about herself. She explores her Jewish heritage, marries a Jewish man and is raising her children as Jews, coming back full circle to the identity and faith of her grandmother.

I found myself caring deeply about these characters, especially determined Estelle. Despite my quibbles with some of the awkward writing and myriad typos, the story is compelling and could have further shined with a copy edit.

The Mother Code: My Story of Loss and Love, and the Myths that Shape Us is an exceptional hybrid memoir that folds in genetics, the history of science and the bewildering world of the fertility industry. Ackerman, a journalist who has written for The New York Times, Forbes and other publications, here writes about the many stops and starts along her road to motherhood.

At the age of 43, Ackerman gave birth to her daughter, Clementine, who was conceived with a donor egg. She writes beautifully about the changes in her life, from initially rejecting motherhood in her 20s to desperately trying to conceive in her early 40s to the decision to use a donor egg.

Ackerman’s journalistic skill and propulsive storytelling lead the reader through the byzantine, often bewildering world of the fertility industry. Along her convoluted path to motherhood, there are indecision, uncooperative partners, divorce and endless negotiation—hearts, careers minds and ovaries are all put on the line.

Ackerman’s greatest ambivalence was freezing her eggs in her early 30s while married to a man who did not want children, assuming that that would keep open the possibility of conceiving later. In considered prose, Ackerman, divorced and with another partner, details her struggles to conceive via IVF and her heartbreak over the embryos that did not survive after they were implanted in her uterus. She writes about desperately grasping for motherhood, even while experiencing bouts of maternal ambivalence (that combination of yearning and guilt that Lowy describes in her book).

Ackerman grapples with the significance of her own family history, including her half-brother’s developmental challenges and the mental illness in her maternal line. “I come from a long line of women who have abandoned their children,” she writes frankly in the opening chapter. “Or at least that’s what I have been told. For as long as I can remember, I’ve heard about how my great-grandmother Kitty and my grandmother Ruth ditched their kids because of men or money or mental problems….”

But the biological and emotional need to have a child triumphed. Despite the difficulties, she wanted to experience childbirth and motherhood in all its glorious messiness, even as she points out the flaws and difficulties with our notion of being a mom.

“From getting pregnant to giving birth to breastfeeding, the idea that there

is a natural—and therefore unnatural—way to do things sets up a dichotomy between the good girls and the failures, between those who follow the “correct” mother code and those who don’t,” she writes about the hard-earned knowledge gained through her experience.

“I now know that the whole idea of motherhood as ‘natural’ is part of the lie that keeps women believing their place is in the home. It’s part of the lie of maternal instinct. Parenting doesn’t come naturally to women more than men. Women aren’t inherently better able to do the emotional and physical labor of motherhood. It’s a skillset that can be learned.”

My own children are long grown and flown, and I find it somewhat ironic that they are both pursuing medical residencies in pediatrics.

At times, I wish I was able to access to this educated version of them in my early parenting years, to ask them for some advice about their younger selves to add to my skillset.

But then again, maybe not. It might have taken away some of motherhood’s thrill and gorgeous mystery—the complexity and myriad paths of being a mother described in these three books.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply