Arts

Henrietta Szold’s Story, From the Granddaughter of Her Lost Love

Abby Ginzberg has a unique perspective on the story of Henrietta Szold. Not only is the Berkeley, Calif.-based documentary filmmaker a distant cousin of the Hadassah founder on her maternal side, but her paternal grandfather, Talmudic scholar Louis Ginzberg, was the man who broke Szold’s heart.

“I stand at this intersection of her broken heart and all the good work she did,” said Abby Ginzberg, 75, explaining what motivated her to make Labors of Love: The Life and Legacy of Henrietta Szold, which will have its world premiere July 26 at the San Francisco Jewish Film Festival and will be screened at the Hadassah National Conference in early August.

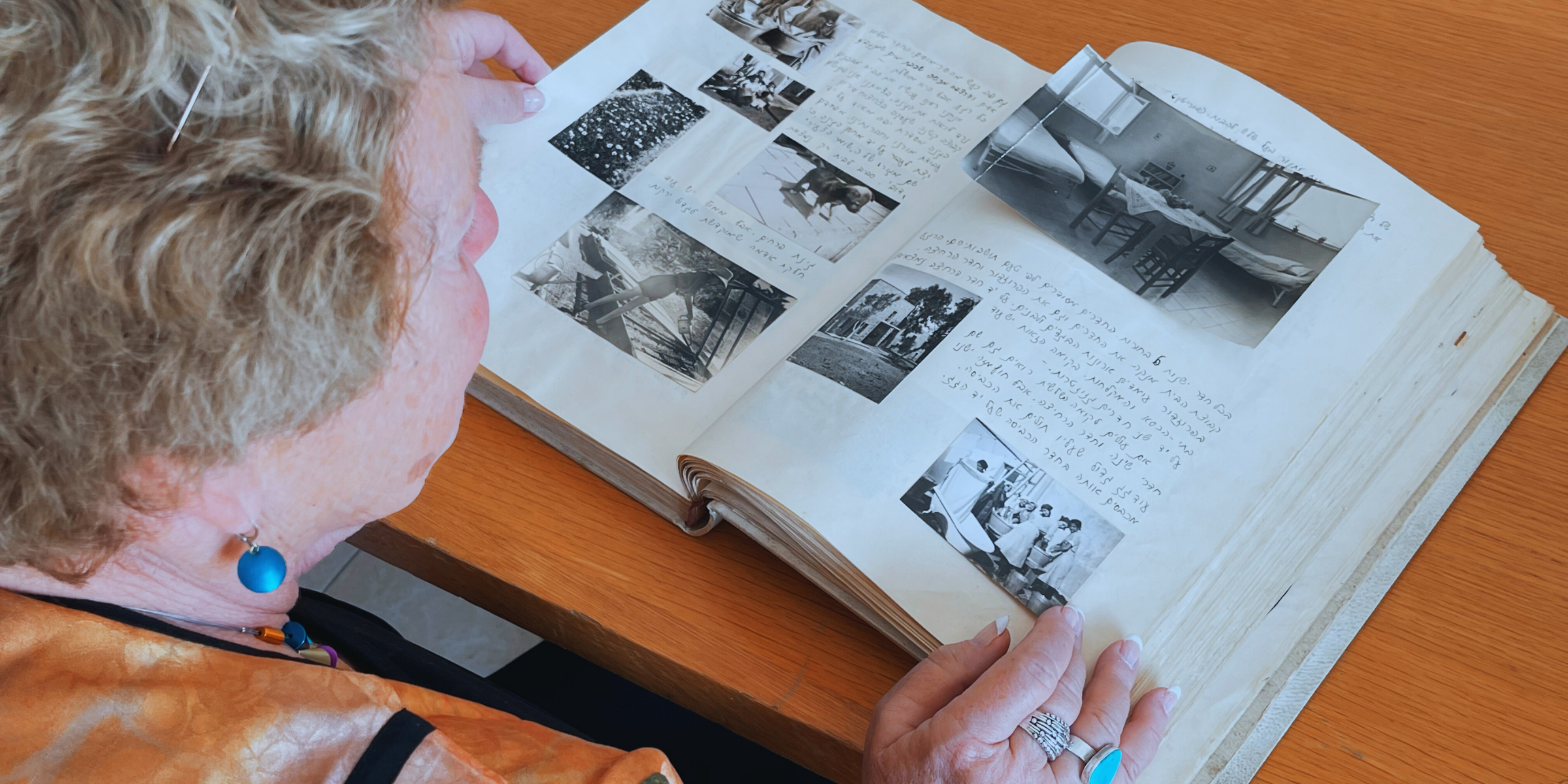

Labors of Love uses photos and video clips of Szold combined with interviews with experts and dramatizations of key moments in the life of the woman who pioneered health care for Jews and Arabs in British Mandate Palestine, saved thousands of Jewish children as director of Youth Aliyah and, in 1912, founded Hadassah, The Women’s Zionist Organization of America. Broadway icon Tovah Feldshuh, who has previously played Golda Meir on stage, reads passages from Szold’s meticulously kept diary, giving a highly personal touch to a story familiar to many Hadassah members.

The Peabody Award-winning Ginzberg began work on the project almost 20 years ago, then put it aside in favor of the social justice documentaries that comprise the bulk of her 35-year career. Among those documentaries is Barbara Lee: Speaking Truth to Power, about former Congresswoman Barbara Lee, recently elected mayor of Oakland, Calif. It won the 2022 NAACP Image Award for Best Documentary. Her Peabody win was for Soft Vengeance, about the South African Jewish anti-apartheid activist and judge Albie Sachs.

Labors of Love is an anomaly, she said, being the only film in her body of work that focused on her subject’s Jewishness. She returned to the project in 2022, first interviewing experts in New York City, then making two trips to Israel to research and shoot scenes from the second half of Szold’s life.

Like many of her other films, this one is about female empowerment. “In that sense, it fits in with my other work,” she said. “I’m telling the story of a woman who inspires me.” But despite her family connection to Szold, Ginzberg says she didn’t know a lot about her.

“I knew I wanted to tell her story, but I didn’t know exactly what part of that story to tell,” she said.

As she got deeper into her research, the focus emerged: Szold as a feminist, activist and person who cared deeply about Jewish survival and Jewish identity but who had a nuanced approach to Zionism.

One of the lesser-known facts that emerges in the film is Szold’s strong and very public support for a binational state, where Jews and Arabs would share power equally. She, along with Judah Magnes and Martin Buber, was one of the founders of the Ihud Party in 1942, a small, binationalist Zionist political party that opposed the establishment of the Jewish State as proposed by the Zionist movement.

“The fears of the Arabs are not groundless,” we hear from a 1942 entry in Szold’s diary. “Is it not our business to see the Arab side, too? I believe there is a solution to the Arab-Jewish problem, and if we cannot find it, then I consider that Zionism has failed utterly.”

“It’s quite intense that she said that,” Ginzberg said. “I knew she’d spent all this time in [British Mandate] Palestine, that she created health care institutions for both Arabs and Jews, and she cared about the Arab people around her, but I didn’t know what else I was going to find out about her attitudes.”

Another filmmaker might have spent little time on Szold’s doomed relationship with Louis Ginzberg in the early years of the 20th century, when the two worked together in New York City on Ginzberg’s manuscripts, notably his multivolume opus, The Legends of the Jews. Szold helped to translate his work while secretly falling in love. At 48, she was 13 years his senior and was devastated when he returned from a trip to Berlin in 1908 with news of his impending marriage to Adele Katzenstein, a young woman of 22—Abby Ginzberg’s future grandmother.

This filmmaker, however, dwells on that relationship, even recreating the final denouement using actors to give it particular emphasis because, she said, of her personal connection to both figures.

“That moment is so pivotal for Henrietta, and I tell it from her point of view,” she said. “I thought, well, that’s something I can do to add to what’s known about her.”

Unlike those who castigate Louis Ginzberg as a cad for leading her on, Abby Ginzberg believes that her grandfather had no idea how Szold felt about him.

“My take on this always was that she projected her feelings onto him,” the filmmaker said.

As for Louis Ginzberg, he was, his granddaughter said, “a total intellectual, definitely inexperienced.” Not only that, she added ruefully, “I think he really felt, of course she’s interested in me, because I’m so interesting. That’s a Ginzberg trait. The narcissism of the men in my family, that was easy to identify.”

Again, thank goodness for Szold’s unrequited love, Abby Ginzberg said. If she had married Louis, or indeed anyone else, she would never have moved to prestate Israel, never founded Hadassah, or set up the country’s tipat halav system, or directed Youth Aliyah—none of that.

“She would have ended up staying home and making matzah ball soup for him, and she would have been fine with that,” the filmmaker said. “I saw what it was like to be Louis Ginzberg’s wife,” alluding to her grandmother.

“She would have been fine, but the world would have been deprived of a lot of great work, of all the good things she did.”

Sue Fishkoff is the former editor of J. The Jewish News of Northern California and the author of The Rebbe’s Army: Inside the World of Chabad-Lubavitch and Kosher Nation: Why More and More of America’s Food Answers to a Higher Authority.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply