Arts

Books

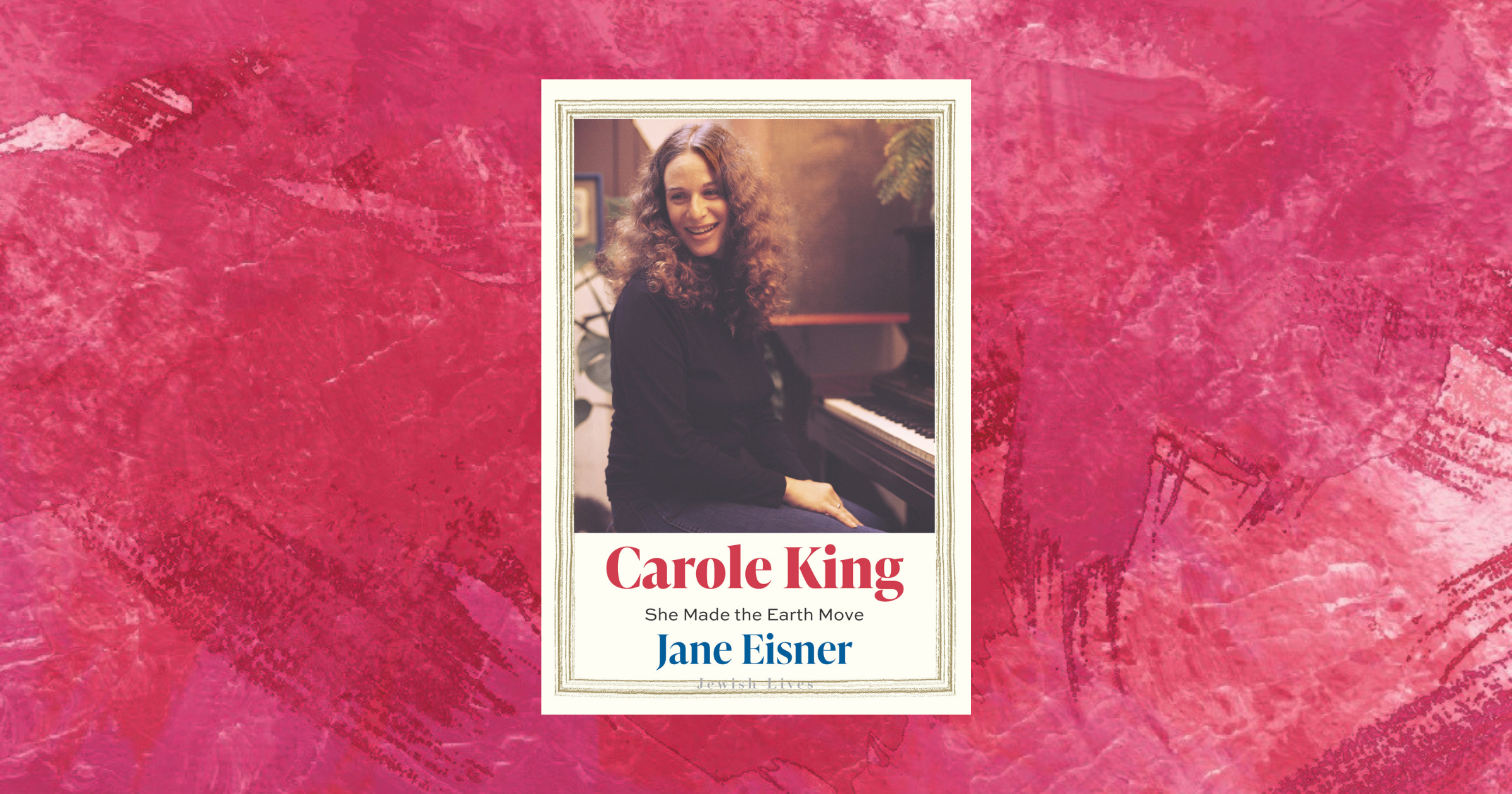

Carole King’s Musical Stardust

I was 15 years old in the summer of 1971. I remember it as a dispiriting time. American efforts in the Vietnam War were failing while public demonstrations grew bolder and more consequential. The Pentagon Papers exposed the government’s lies to the public. Inflation was rising. After the tumultuous 1960s, the nation was anxious and exhausted.

For many of us stuck in crowded, troubled high schools in chaotic cities or listless suburbs, music offered a powerful release. One artist emerged with a voice and a sound like no other. Carole King was different from anyone we had seen or heard before, with her unabashed curly hair, authentic voice, unforgettable melodies and lyrics that seemed to innately understand who we were and who we wanted to be. Tapestry, released in spring 1971, soared to musical stardom, a groundbreaking album of deeply personal songs that set a new path for the emerging singer-songwriter movement.

She was ours. Especially at Lake Waubeeka.

In the early 1950s, back when she was Carol Klein—before she added the ‘e’ to distinguish herself from other Carols in high school, and before she changed her identifiable Jewish name to a pareve stage name—her father, a firefighter, along with other New York City Jewish firefighters, built a bungalow colony for their families near Danbury, Conn. King spent her summers there swimming in the lake and cavorting with other teenagers—a welcome escape from the tiny Brooklyn apartment she called home.

The founders of Lake Waubeeka named the streets for their children. In that summer of 1971, and the summer afterward, I lived with my family for several weeks at 55 Carol Street in a home owned by my aunt and uncle (by then you didn’t need to be a firefighter to join the community). While they traveled, my mother kept house and my sister, Karen, and I watched our younger cousins. My father, who worked in the Bronx, joined us on weekends.

Every morning that first season in the colony, we’d amble down to the community center to hang out during rehearsals for an amateur production of West Side Story. The director, who had the musical flair of a Broadway maestro and a teacher’s knack for encouragement, was Genie Gingold, King’s mother, who had remarried after her divorce from Sid Klein.

My sister remembers a rainy day when we sat with Gingold’s two young granddaughters who were singing a new song that “Uncle James” had taught them.

That would be James Taylor. The granddaughters were Louise and Sherry Goffin, King’s first two children.

We were that close to the creator of Tapestry, sprinkled from a distance with a bit of musical stardust. There was a frisson of excitement about that moment, and a thrum of anticipation. Would Carole King herself visit? Lurking beneath was an even weightier question: Could we, too, transcend humble beginnings to achieve some sort of greatness, if only we had enough talent and determination? She was from Brooklyn; we were born in the Bronx. Was the world really open to women like us?

It was, at least for some. King’s meteoric rise in popular culture was fueled by her extraordinary talent, her outsized ambition and her exquisite timing. She came of age when the children of the working class in New York City’s outer boroughs were driven by striving parents and benefited from excellent public education.

James Madison High School, from which King graduated in 1958, nurtured her musical aspirations. The subway allowed her to easily reach midtown Manhattan, where she could sell her songs to music producers. Antisemitism was declining, and King’s Jewishness—the name change couldn’t hide it—was not a hindrance to success. Women were starting to be taken seriously. And popular music in the city was a thrilling blend of racial and ethnic influences, offering just the kind of excitement that King craved.

When I was given the opportunity to write a biography of King, I didn’t realize the extent to which that micro-era—the late 1950s and early 1960s—shaped popular culture for years to come. There was something in the air that propelled the lasting contributions of King and so many of her peers, including Barbra Streisand, Neil Sedaka and others.

Similarly, a decade later, a combination of environment, industry, politics and newfound personal freedoms made the Laurel Canyon section of Los Angeles the place to be for musicians like King. That’s where Tapestry and the notable albums that followed were born. That’s where King became not only a composer and arranger, but a lyricist and performer.

All this I learned while researching Carole King: She Made the Earth Move, part of Yale University Press’s Jewish Lives book series. I also learned to appreciate King’s music in a new way, beyond the swooning delight of a teenager to a deeper understanding of her original musicality.

I decided early on that to best describe her music, I should play it on the piano, her native and signature instrument. But my skills were so rusty that I needed help, so I studied piano for two years, with the main intent to play her iconic songs from Tapestry.

At my age, it wasn’t easy! Many of her well-known songs seemed basic, catchy but not complicated. Wrong. Underneath that aura of simplicity are complex chords that provide texture and emotion. Musicians speak of the “Carole King chord,” which she did not invent but did employ to unusual success. I also learned how she stretched the conventional structure of a popular song to create new modalities. And how she overcame her fear of performance to use her own voice to lend authenticity to her work.

King, now 83 and living in Idaho, is notoriously media-shy, for reasons I can’t entirely explain, and I knew from the start that it would be extremely difficult to secure an interview. Despite my journalistic know-how, and my ties to Lake Waubeeka, I was unable to speak to her, though I did interview many of her classmates and associates. I even tracked down her rabbi in California and her son’s bar mitzvah tutor!

There’s an inherent risk in biographical writing that the author will come to sympathize so much with the subject that a book becomes a hagiography. Without being able to meet her, I was instead able to maintain an analytical distance, writing critically about her later, forgettable albums and her messy personal life. In my opinion, that makes for a far more interesting character study.

King is a complicated woman, who both shies away from fame and courts it, who achieved unimaginable success early in her life and faced crushing expectations for years afterwards.

In the end, it is her music that endures.

Jane Eisner is a veteran journalist and former editor-in-chief of the Forward. Her latest book is Carole King: She Made the Earth Move, slated to be published in September by Yale University Press as part of the Jewish Lives series.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Susan Cohen Grossman says

If I just said “wow” that would be an understatement. My formative time at age 18 traveling across the US was dominated by “it’s too late baby”, Carole’s popular song then. It’s still in my musical memory so when I recently heard that Jane Eisner was coming to CA, I had to meet her and hear the music again. This Sunday at my synagogue in Walnut Creek, California (https://bshalom.org/) both the memories and Jane’s wonderful speaking/storytelling voices will be happening. Our Hazzan, Sandy Bernstein, will give life to the music and I will be 18 once again for a few brief moments! I hope that Hadassah people turn out in great numbers. We have a thriving Hadassah Evolve community and the Diablo Valley chapter who are supporting this wonderful program! Thank you for this amazing interview and for giving voice and music to my age 18 soul!