Books

Health + Medicine

A New Graphic Novel Reimagines Surrogacy

When it comes to discussions of surrogacy—when a woman carries and gives birth to a baby for another person or couple—the media often sensationalize the topic with stories about celebrities using underpaid women who are exploited in “baby factories” in countries such as Ukraine or Nigeria, or greedy women looking to make a quick buck.

But in A Tale of Two Surrogates: A Graphic Narrative on Assisted Reproduction, Israeli anthropologist Elly Teman, senior lecturer at Ruppin Academic Center in Emek Hefer, in central Israel, and Jewish American sociologist Zsuzsa Berend, a lecturer at the University of California, Los Angeles, dispel those stereotypes and portray stories of two fictional women primarily motivated by altruism.

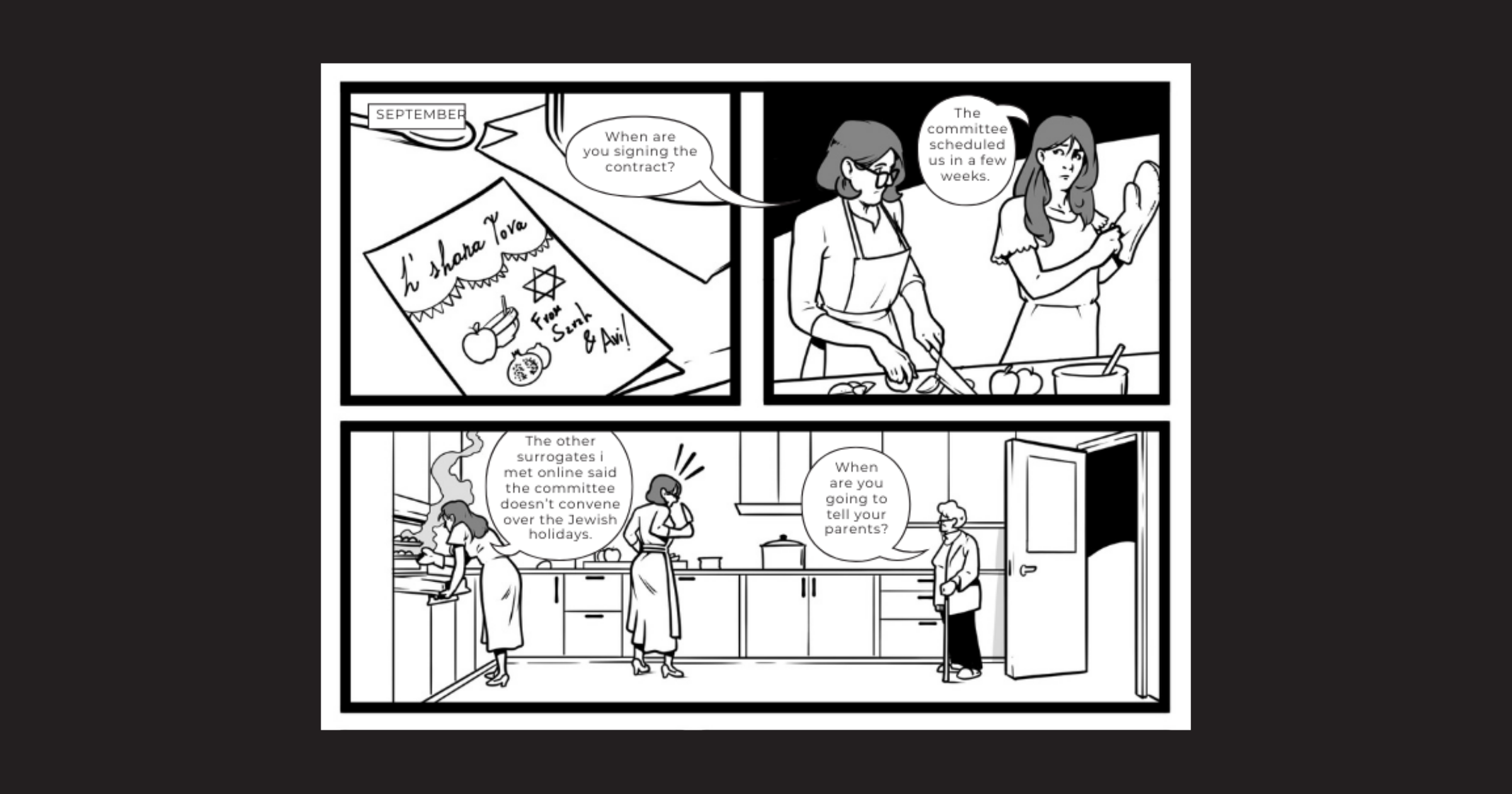

Illustrated by Andrea Scebba with crisp and accessible black-and-white imagery, the graphic novel follows the lives of Jenn in America and Dana in Israel, both married working moms, and the different paths they take to help infertile couples by becoming gestational surrogates. (In gestational surrogacy, the egg used does not belong to the surrogate, who is typically impregnated via in vitro fertilization.)

“I wanted to do something that could reach people who would never read an academic article,” said Teman, who grew close to several surrogates through research she was conducting a few years after surrogacy became legal in Israel in 1996 (though there were restriction on who can use or be a surrogate). In 2014, it became legal for married women in the country to become surrogates, and in 2022, the ban on gay couples and single men using surrogates was lifted.

In the United States, the legal landscape for surrogacy varies significantly by state. Some states, such as California and Nevada, are considered fully surrogacy-friendly by reproductive assistance groups, allowing for surrogacy for couples and individuals regardless of marital status and sexual orientation and with legal frameworks that protect both surrogate and intended parents. Others restrict or prohibit surrogacy; for example, Louisiana bans compensated surrogacy but allows altruistic surrogacy for heterosexual couples.

The new graphic novel is a vivid portrait of the inner worlds of surrogates, in the process challenging assumptions and offering a nuanced take on autonomy, kinship and the meaning of motherhood. In a phone interview, Teman spoke about developing the graphic novel and the distinctions and similarities between surrogacy in Israel and the United States. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Why did you decide to write this book?

During the pandemic, stuck in my apartment, I wanted to do something creative. I really wanted to explain to intended parents what goes on in the lives of the surrogates. Zsuzsa and I had written these comparative articles about how surrogates explain their choice to their kids and how they negotiate it with their husband or partner, and how they think about themselves as “not the mom.” We wanted to show the ups and downs and the whole complexity of it, what would be useful to people.

A lot of intended parents have asked me, “How do we relate to the surrogate after the birth?” And I always say, “She doesn’t become Lilith or a monster after the birth. She doesn’t want your baby. She wants to see you as parents. She’s bonded with you, not with the baby.”

In her American research, Zsuzsa often found that surrogates and intended parents did not live nearby—as they often do in Israel—and the physical distance created an emotional distance, and that surrogates wanted more of a relationship. In the book, Jenn is constantly trying to engage, and Anne, the intended mother, is not cooperating the way she expects her to.

What are the differences between the legal cultures in Israeli and American surrogacy?

Israel’s law is so strict. Each and every contract is regulated by a state committee. So surrogates’ rights are very well protected and intended parents’ rights are very well protected. As with most things in Israel, the committee enters your life and your body and your womb. The state is very paternalistic and is trying to protect people not to do something to harm themselves—physically, emotionally, in all ways.

In the United States, Zsuzsa found that because it’s state by state, oftentimes the surrogates have to negotiate their rights on their own and advocate for themselves in the contract. The surrogates as a collective empower one another to make educated choices.

How do Israeli and American surrogates perceive their experiences?

A lot of the Israeli surrogates are feminists, and they have this narrative that they’re not exploited—they’re surrogates by choice. In the Israeli surrogacy groups online, they say that no one should speak for them, they can speak for themselves. It’s part of a feminist ideal: “I’ll make choices about my body, and I’ll make choices about what I do, and I know what I’m doing—don’t tell me I’m exploited.”

It’s not the same feminist narrative for American surrogates, though they also believe that no one is exploiting them, that they’re just helping other people. And they see themselves as individually responsible for what they’re doing.

What is your impression of the money-hungry stereotype of surrogates?

Both of us found in our research that the money’s nice, but that’s not usually their so-called one motivation. Among their motivations is to do something special. In Israel, 60 percent of surrogates are religious women from yishuvim, settlements, who do a lot of chesed. In Israeli society, one of the biggest mitzvahs is to help people become parents.

These women tend to carry for other religious couples. They often feel more comfortable that way—sharing similar values, lifestyle, modesty norms, that kind of thing. It’s not an official requirement, but it’s definitely a common preference.

Do you have a personal connection to fertility struggles?

I have three children and never used in vitro fertilization myself. But my brother and his wife went through tons of IVF. After seeing my 20 years of research on surrogacy, six years ago, they worked with a surrogate. And now I’m the aunt of a miracle baby.

Amy Klein is the author of The Trying Game: How to Get Pregnant and Get Through Fertility Without Losing Your Mind.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Dorothy says

I learned something very new from the article.