The Jewish Traveler

Jewish Life in the Western Balkans

Eighty years after the Shoah and 30 years since the breakup of the former Yugoslavia and the tumultuous wars that followed, the Jewish community of the western Balkans proudly holds on to its traditions. With approximately 700 Jews in mountainous Bosnia and Herzegovina and about 175 in Croatia’s Adriatic coastline cities of Dubrovnik and Split, these small communities continue to demonstrate their resilience.

“There’s a strong sense of identity and ongoing efforts in education, cultural preservation and engagement with younger generations,” said Igor Bencion Kozemjakin, the cantor and spiritual leader of Sarajevo’s Jewish community. (The city has not had a permanent rabbi since 1968). “We want to continue to live as a religious community.”

That sentiment echoes the resolve of all the region’s residents, who lived through the devastating wars in the 1990s that followed the breakup of Yugoslavia and claimed the lives of more than 100,000 people. The Bosnian civil war, the largest battleground, involved Bosnia’s three main ethnic groups: the Muslim Bosniaks, Eastern Orthodox Serbs and Catholic Croats. Bosnia’s capital, Sarajevo, endured a nearly four-year siege from April 1992 to February 1996, resulting in the death of over 11,000 people.

The first Jewish community in Bosnia and Herzegovina was established in Sarajevo in 1565 by Sephardim fleeing the Inquisition that had begun in 1492. They built their own quarter, El Cortijo (the courtyard), and the city’s first synagogue, today known as the Old Sephardi Synagogue.

Ashkenazi Jews arrived following the country’s annexation to the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the end of the 19th century, building a synagogue in 1902 and forming their own community that lasted until World War II. In 1941, the country came under the control of Nazi-aligned Croatia and its Fascist Ustasha party. Only 2,000 of the 12,000 Jews living in Sarajevo prior to World War II survived. The majority were killed in concentration camps in Croatia, the most notorious being Jasenovac, or in Auschwitz.

There are close to 350 Jews in Sarajevo today, but just 50 to 60 regularly attend services at the Moorish-revival Ashkenazi Synagogue, the only synagogue still in use in the city. Its main sanctuary features enormous arches with richly painted decorations and an ornate ceiling decorated with 10-pointed stars.

Sarajevo Jewry has long been hailed for its humanitarian organization La Benevolencija, which, during the Bosnian War, helped distribute supplies and medical care to those in need regardless of ethnic or religious identity. Such interfaith cooperation is one of the reasons why the city has earned the moniker the “Jerusalem of Europe.” La Benevolencija still operates, staging cultural events and offering a variety of services.

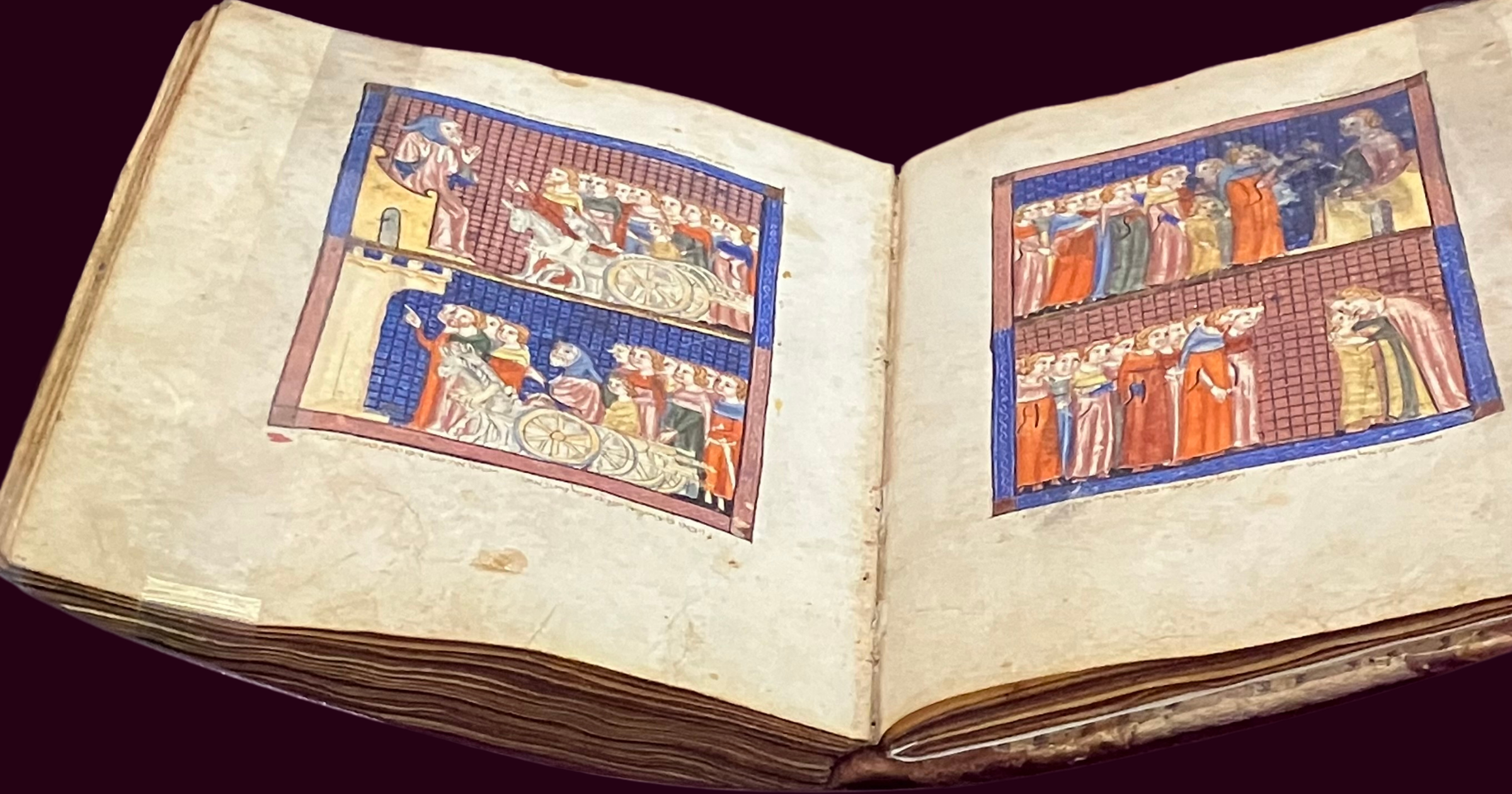

The famed Sarajevo Haggadah—and the heroic efforts to preserve it—had been another testament to interfaith cooperation until just recently. The illuminated manuscript, housed in the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, is believed to have been created in northern Spain during the second half of the 14th century. It left the Iberian Peninsula with Jews who were expelled in 1492 and ultimately came to Sarajevo and was sold to the museum in 1894. The manuscript survived World War II after a Muslim curator smuggled it out, and the Bosnian War when curators again preserved it for safekeeping. But in August, the museum announced that ticket sales to see the haggadah as well as proceeds from a new book about it would be donated to Palestinian causes, in protest of Israel.

While most of Bosnia’s Jews live in Sarajevo, smaller communities are scattered in cities such as Banja Luka, Doboj, Tuzla, Zenica and Mostar.

Mostar, located about two hours southwest of Sarajevo in Herzegovina, the southern region of the country known for its Mediterranean climate and dotted with mountains, rivers and waterfalls, has become a popular tourist destination. Its iconic Old Bridge (Stari Most), which dates to the 16th century and spans the Neretva River, was destroyed during the Bosnian War and later rebuilt.

Sephardi Jews began settling in Mostar in the middle of the 16th century yet only established an official community in 1850, according to local tour guide Borna Tomic. Ashkenazi Jews arrived when it became part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1878. By the eve of World War II, there were more than 300 Jews. The small surviving community, today dwindled down to about 30, donated its synagogue in 1952 to be used as a puppet theater.

Every year, Bosnian Jews visit the tomb of Rav Moshe Danon in Stolac, south of Mostar, to honor his yahrzeit. Danon, the chief rabbi of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1815, had been imprisoned in Sarajevo along with 10 other Jews who had been falsely accused of murdering a Jewish convert to Islam. Local Muslims liberated them from prison, and the country’s Jews continue to celebrate the miracle of their survival every fall with the Sarajevo Purim, reminiscent of how the Jews of Persia were spared in the original Purim megillah. Later, Danon set out for Jerusalem but died—and was buried—in this bucolic town.

From Mostar, it is a couple hours’ drive to reach the Croatian cities of Dubrovnik and Split along the Dalmatian coast. Matija Singer, the vice president of Dubrovnik’s 75-member Jewish community, said that Jews first arrived in the city in 1325. Their status ebbed and flowed over the years, with the population never surpassing 500. On the eve of the Holocaust, Dubrovnik was home to 250 Jews, all but 28 of whom survived thanks to an active resistance movement and protection from local non-Jews, according to Singer.

Dubrovnik has no permanent rabbi, but the community receives support from religious leaders in Zagreb, the capital where the majority of Croatia’s 2,000 Jews reside. The Old Town is home to what is thought to be the world’s oldest active Sephardi synagogue in Europe, known simply as Dubrovnik Synagogue or Old Synagogue, which was built around 1352.

In the equally stunning port city of Split, Jewish history dates to around 600 CE, when Jews sought shelter near Diocletian’s Palace, the vast complex built by the Roman emperor in 305 CE and which later formed the core of the city. In the eastern section of the palace, carvings of what appear to be menorahs—albeit with only four branches—hint at a Jewish presence.

By the end of the 15th century, Split had become a refuge for Sephardi Jews expelled from Spain. While the Jewish population never exceeded 350, they represented 10 percent of the population at their peak in the late 18th century, according to tour guide Lea Altarac, whose paternal grandparents were Bosnian Jewish refugees who joined the partisans in World War II. There were approximately 250 Jews in Split before the war, she said, during which 80 percent were murdered, most in Ustasha-run concentration camps.

Abutting the western wall of Diocletian’s Palace is the Split Synagogue, which was created in 1510 by combining the second floors of two medieval houses. The 100-member congregation gathers for Friday night dinners and holidays and periodically welcomes rabbis from Zagreb to lead services.

Despite its small size, “our goal is to keep the local community together” and be available for tourists, Altarac said. Although her mother’s family is not Jewish, she added, Judaism is “the only heritage I have ever known.”

Where to go

Bosnia and Herzegovina

The Ashkenazi Synagogue, built in 1902 as the only Ashkenazi house of worship in Sarajevo, today follows Sephardi rites. A small Friday night dairy/pareve meal is held weekly. To participate, contact recepcija.josa@gmail.com.

The Old Sephardi Synagogue was founded in 1581 by Sephardi Jews who settled in Sarajevo after their expulsion from Spain. Today, this annex of the Museum of Sarajevo hosts the Jewish Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Its upper balconies display artifacts that detail centuries of Jewish life in Sarajevo, photographs of Sephardi luminaries, traditional clothing and Holocaust-related exhibits.

During the 1992-1995 Bosnian War, Sarajevo was besieged by a ring of more than 35 miles of Bosnian Serb tanks, machine guns, rocket launchers and snipers. Three hundred people—digging by hand under candlelight—built a tunnel in four months under the runway of the airport to transport essential supplies, weapons and people out of the capital. Known today as the Tunnel of Hope or the Tunnel of Salvation, visitors can walk through one of the original entrances and a section of the tunnel.

Housed in its own climate-controlled room in the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Sarajevo Haggadah comprises 142 leaves of parchment. The first 34 leaves feature illuminated biblical scenes such as the creation of the world. The next 50 leaves contain the text of the Haggadah, written in a medieval, Spanish-type square script. The last section includes poems by luminaries of the golden era of Hebrew literature—the 10th through the 13th century—such as Yehudah HaLevi and Salomon ibn Gabirol.

Run by a Sarajevan Jewish couple, Eli and Mirjam Tauber, Association Haggadah was established to promote Jewish culture in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The association and its gift shop are housed in a former Sephardi synagogue that now serves as the Bosnian Cultural Center.

The 16th century Latin Bridge spanning the Miljacka River is famed for its proximity to the June 1914 assassination of the Austro-Hungarian heir to the throne, Franz Ferdinand, and his wife, Sophie, an event that triggered the outbreak of World War I. The Museum of Sarajevo 1878-1918 is located on the actual assassination site and provides historical context.

The second-largest Jewish cemetery in Europe, the Old Jewish Cemetery in Sarajevo dates to the 1630s and contains 3,850 tombstones. Damaged from mines and shelling during the Bosnian War, the burial grounds were restored and proclaimed a national monument in 2004.

In the Old Town in Mostar, sit at a cafe overlooking the Neretva River and its 16th century Old Bridge to be transported to a lush storybook setting, surrounded by greenery as well as architecture reflecting the city’s Ottoman past and more recent European influences.

In Stolac, faded Hebrew writing marks the plain burial stone at the grave of Rav Moshe Danon, which is surrounded by a stone pathway shaped like a menorah.

Croatia

The Dubrovnik Synagogue’s Baroque-style interior features a blue-and-white painted ceiling and low-hanging chandeliers set against stark white walls. Just outside of the building, which also houses a Jewish museum, are signs of a former foot bridge that connected the synagogue with the property across the street, the only trace of which is indicated in the Hebrew phrase “Baruch atah b’tzetecha” (blessed are you in your departures) carved into the wall.

Diocletian’s Palace is the main tourist attraction in Split. Today, the ruins of the palace lie in the heart of the city and are surrounded by shops, cafes, hotels and apartments.

The Split Synagogue was built in the early 16th century after the original structure, most likely dating from Roman times, was destroyed in a fire. The sanctuary features a blue-and-gold painted ceiling that tops a snug room encircled by white arches and hanging lamps.

Lori Silberman Brauner, former deputy managing editor at the New Jersey Jewish News, visited Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Dalmatian coast of Croatia as a guest of Fortuna Tours. She is currently working on a book about Diaspora Jewish communities.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply