Books

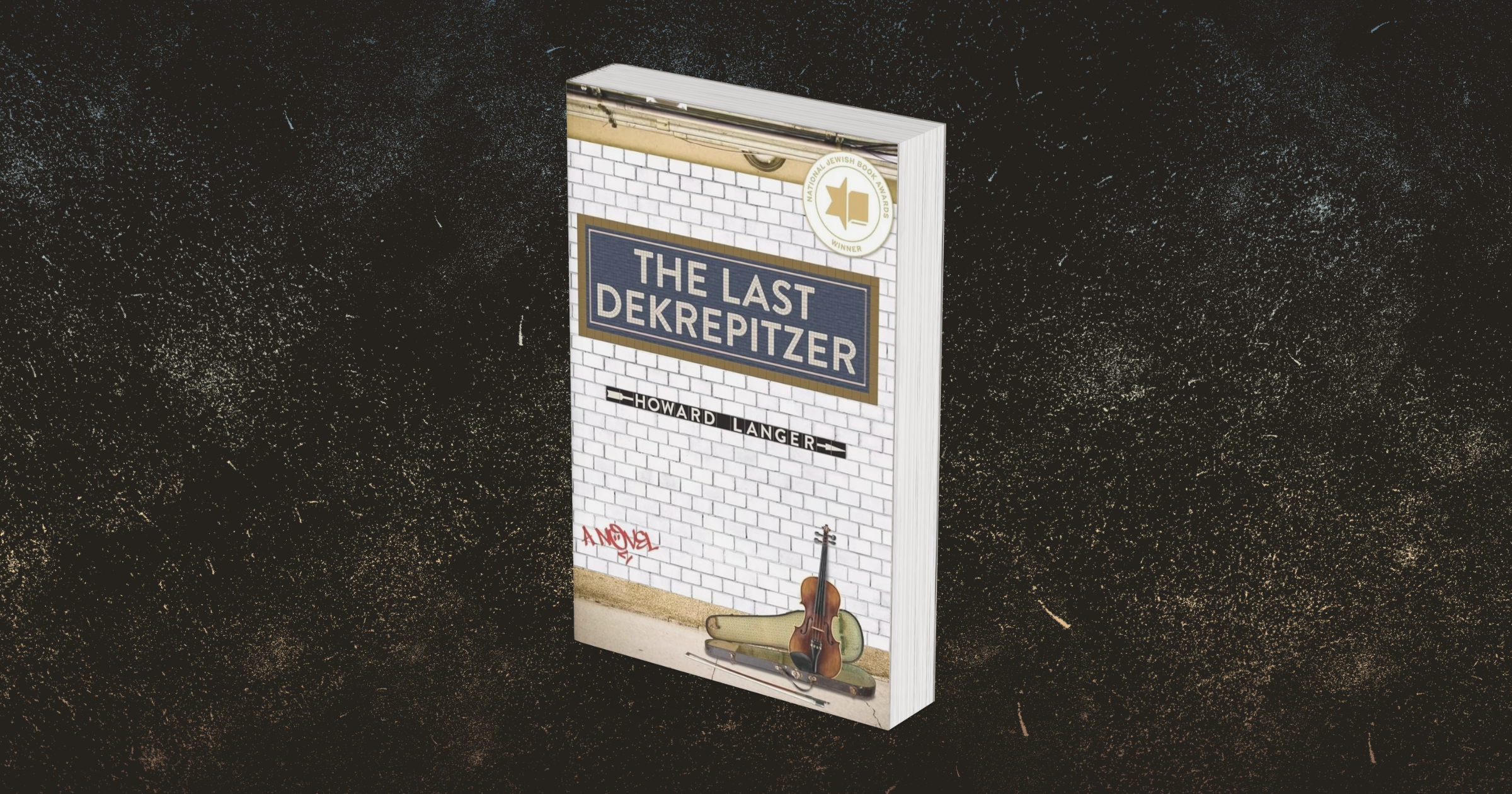

REVIEW: ‘The Last Dekrepitzer’

The Last Dekrepitzer

By Howard Langer (Cresheim Press)

The narrative of this affecting work of fiction, which was recently named the winner of the National Jewish Book Awards’ Book Club prize, is straightforward. Rabbi Shmuel Meir Lichtbencher is the lone survivor of a small Polish Hasidic sect, the Dekrepitzers, who were wiped out during the Holocaust. A rebbe without a congregation wandering through the chaos of postwar Europe, he is also a master fiddler whose niggunim—wordless Hasidic melodies—capture the attention of Black G.I.s in Naples, Italy, who bring him back with them to Mississippi after World War II.

In the United States, Shmuel Meir is renamed Sam Lightup, and he acclimates to life in a rural, segregated Black community where he learns English from the locals, becomes a chicken farmer and shochet (ritual slaughterer), plays the blues with a band called the Brown Sugar Ramblers and teaches and preaches Jewish Bible stories at the local church. He also finds love with a Black schoolteacher named Lula Curtin, whom he marries after assisting in her conversion according to the laws of Orthodox Judaism.

Eventually, Shmuel Meir and Lula have a baby, whom they name Moses. Yet the family finds life in Mississippi, where anti-miscegenation laws were on the state books until the 1980s, untenable. Shmuel Meir makes his way to New York City (his wife and son join him later), where he becomes an apprentice to an Austrian Jewish émigré, Schiff, the go-to violin restorer for the likes of Yehudi Menuhin and Nathan Milstein.

Shmuel Meir soon becomes an expert luthier himself. It is in New York City, halfway through this slim novel, that Langer’s prose soars. There, the author deftly shows, rather than spells out, Shmuel Meir’s fury at an Almighty who would allow for the genocide of his faithful followers.

The niggunim that he plays on the city’s streets and in its subways are not so much an expression of a man’s love for soulful, transformative tunes as they are a rebuke of a higher being. He also refuses to utter traditional Jewish prayers meant to strengthen personal faith. When others say the Shema, Shmuel Meir takes to his fiddle, calling his music “a kind of prayer,” as he tries to explain to a professional violinist toward the end of the book. “ ‘My playing, my playing…my playing a…’ He paused to find the word, ‘a reproach to God.’ ”

Beyond the nuanced, multidimensional portrait of its protagonist, the book excels on many levels. Its lyricism in its description of New York City institutions of yesteryear, including Steinberg’s Dairy Restaurant on the Upper West Side, is tempered by the articulation of certain inconvenient truths about the human propensity for prejudice—and worse. And it is also a reminder, particularly during these divisive times, of a period in history when Jews and Blacks found common ground in their respective struggles.

Robert Nagler Miller writes frequently about the arts, literature and Jewish themes from his home near New York City.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply