Being Jewish

Holocaust Diary Gets New Life 80 Years After Author’s Death

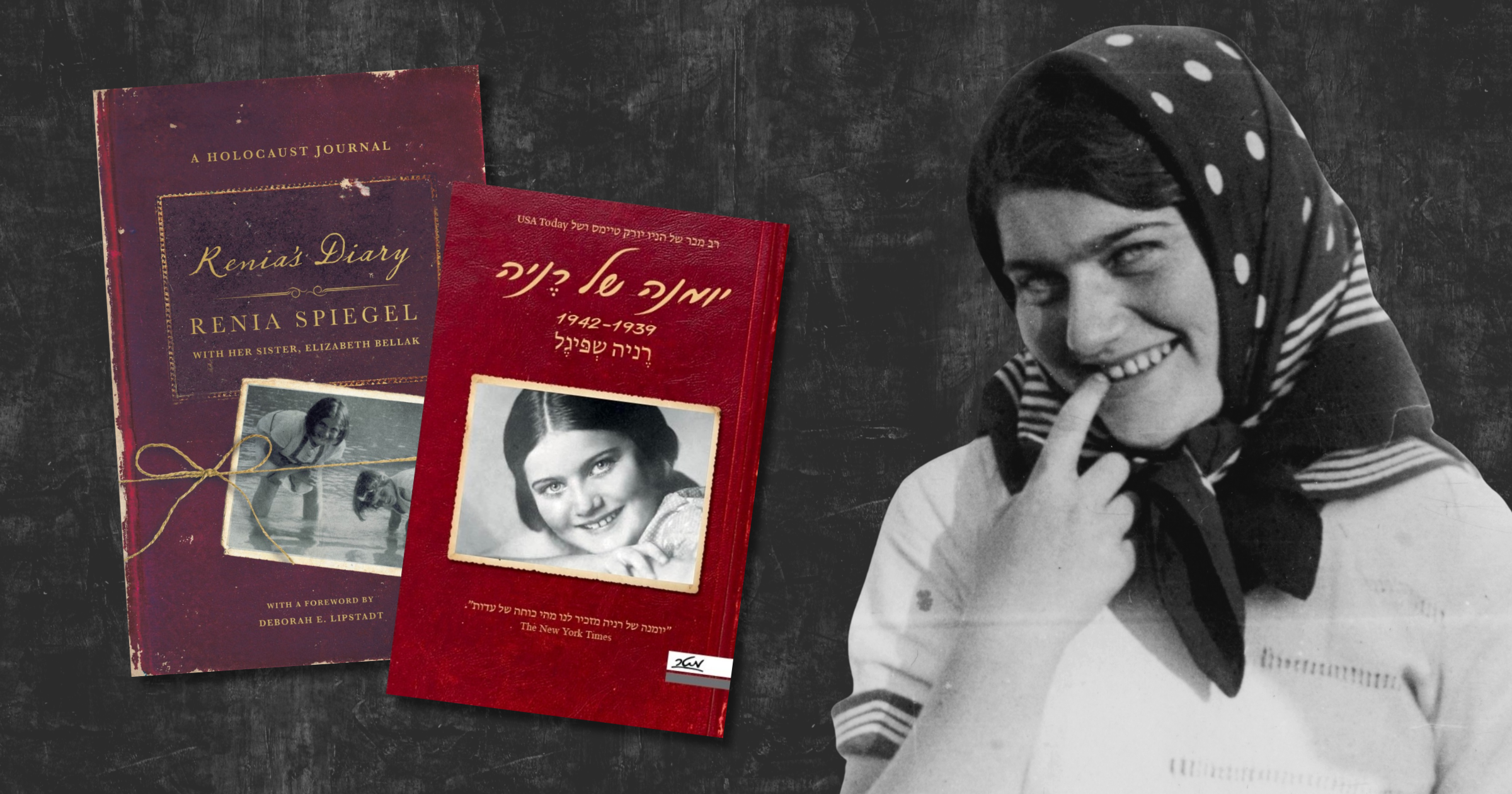

A best-selling diary written by a Jewish teenager in Poland during the Holocaust is receiving renewed worldwide attention more than 80 years after her death.

Renia’s Diary, written in Polish by Renia Spiegel between 1939 and 1942, has now been translated into Hebrew for its recent publication in Israel, after its initial 2019 release in the United Kingdom, the United States and 21 other countries. A webinar about the diary was recently developed by the Jewish Museum of Galicia to help train Polish and American educators how to use it to teach the Holocaust. And the museum has launched an exhibition, “To Leave Something to the World: Beyond the Diary of Renia Spiegel,” with short films, archival photographs and explanatory historical panels, that is traveling in Poland before its expected debut in the United States.

The diary—which made The New York Times best-seller list when it was published in the United States and led to the documentary, Broken Dreams, among other projects—begins in January 1939, when Spiegel is 15. She is living with her grandparents in the small city of Przemysl while her mother, Roza, and younger sister, Ariana, a child actor billed as the “Polish Shirley Temple,” remain in Warsaw.

Similar to Anne Frank’s diary, Spiegel’s is remarkable for its focus on everyday life amid war and tragedy. She intersperses her own lyrical poetry with drawings and comments about typical teenage interests, including a romance with a boy named Zygmunt Schwarzer.

As rumors swirl that the city’s Jews will be forced into a ghetto, on May 9, 1942, Spiegel wrote: “Ghetto again. Oh, God! How much can we take? Who knows where we’ll live and how?”

Schwarzer, who was involved in the resistance, smuggled Spiegel out of the ghetto and into hiding with his parents, but the Nazis discovered them and murdered Spiegel and his mother and father in Przemysl on July 30, 1942. Schwarzer was later deported to Auschwitz.

Roza and Ariana Spiegel survived and eventually immigrated to New York City. Ariana, now known as Elizabeth Bellak, taught school, married and had two children. She celebrated her 95th birthday in November.

“I feel great about my sister being known in the world today,” Bellak said, adding that she is “very proud of her” for writing the diary and “happy that the young people will know about the situation of the Jews living under a fascist regime.”

Schwarzer also survived and moved to the United States. In America, he gave the diary to Roza Spiegel, but both she and Bellak said it was too painful for them to read. It remained unopened in a safe deposit box until 2012, when Bellak’s daughter, Alexandra Bellak, had it translated into English.

“We have to keep these stories alive and relevant,” Alexandra Bellak said. In light of rising antisemitism around the world, she noted, “I hope the diary is a compass for us.”

Peter Ephross, the editor of Jewish Major Leaguers in Their Own Words: Oral Histories of 23 Players, is a longtime writer about the Jewish world.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply