Arts

A Showcase of Female Illustrated Post-WWII Books and Diaries

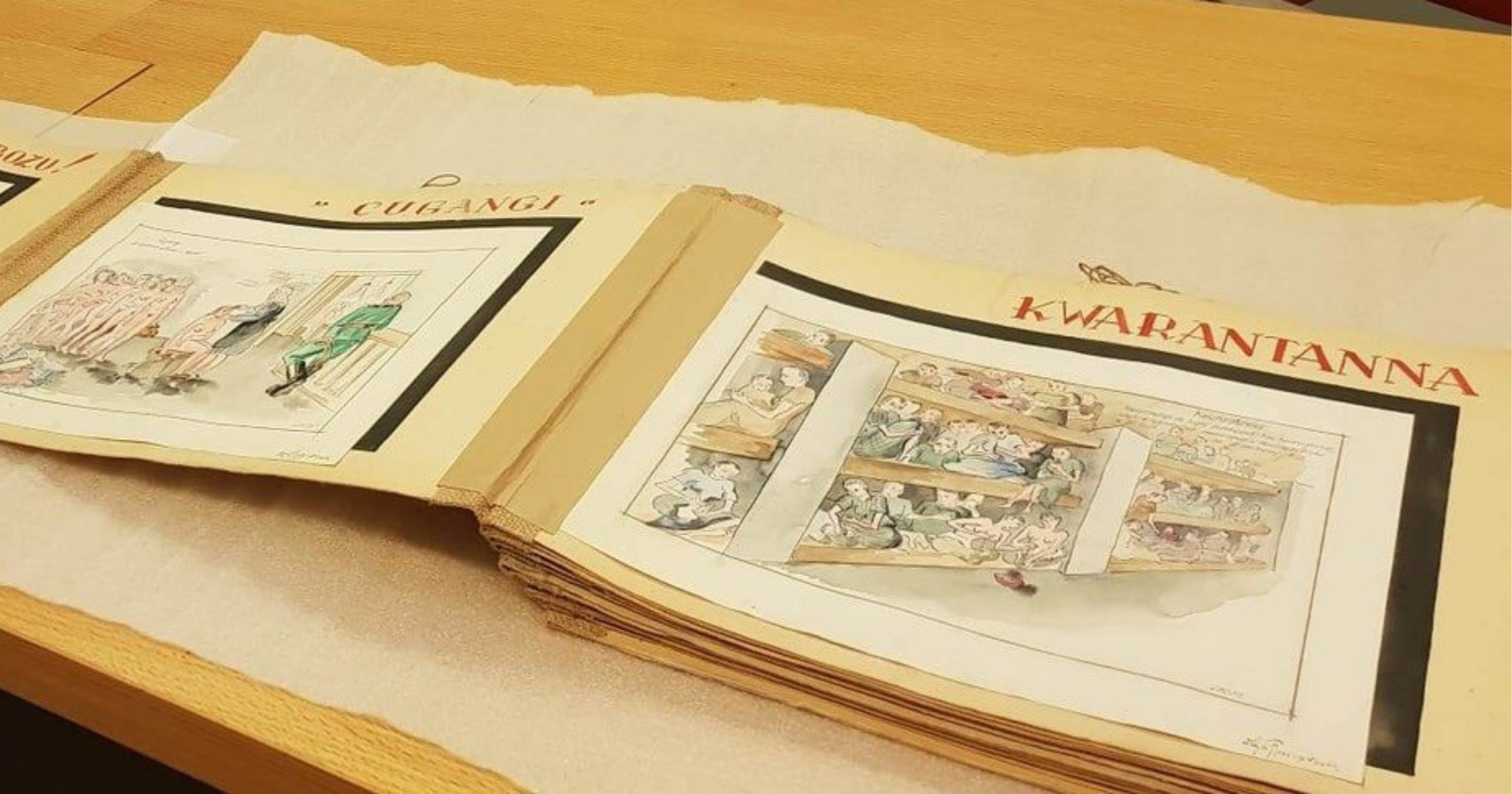

The 20-foot-long accordion book of 19 watercolor and pen-and-ink drawings is titled Auschwitz Death Camp. Its illustrations tell a damning story of the experiences of Jewish women in the infamous camp. Among the chilling images is one of women being beaten by soldiers. Another depicts the crowded bunks, and a third, a naked woman having her head shaved while an SS soldier looks on and leers.

Made of one long piece of paper folded into smaller sheets in a zigzag pattern, the oversized book was created in 1945 by Zofia Rozenstrauch, after the Warsaw-born architecture student was liberated from Auschwitz. The renderings of the camp’s buildings, fences and watchtowers are crisp and detailed—architectural precision serving as the backdrop to horrors. Indeed, the illustrations were detailed enough to be used to help convict Adolf Eichmann in his trial in Israel.

The book is one of the highlights of a new exhibition, “Who Will Draw Our History? Women’s Graphic Narratives of the Holocaust, 1944-1949,” at the Kniznick Gallery for Feminist Art at the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute in Waltham, Mass. Rozenstrauch is among the 10 female survivors whose artwork—drawings and illustrations from handmade albums, pictorial diaries and other works on paper—is featured in the exhibition, which opens on January 27, International Holocaust Remembrance Day, and runs through April 30.

Curated by art historian and Holocaust researcher Rachel E. Perry and based on her forthcoming book of the same title, “Who Will Draw Our History?” presents new scholarship on the Jewish female artists who survived the Holocaust and responded creatively in the immediate aftermath. Many displayed or published their creations, only to have their work disappear into scattered archives and largely fall into obscurity—until now.

Perry, who teaches Holocaust studies at the University of Haifa and at Gratz College in Philadelphia, describes the works in the exhibition as “image albums,” wordless narratives that function as eyewitness accounts no less than written diaries and oral testimonies. The show includes both specially crafted facsimiles and original pieces, most created between the end of World War II and the founding of Israel. A number of the artists began reproducing their experiences within days of liberation or while still in displaced persons camps.

“This is a period when survivors, including displaced persons, are creating while their memories were still fresh,” Perry said. The artworks were created with a sense of urgency, she explained. “They were meant to be seen.”

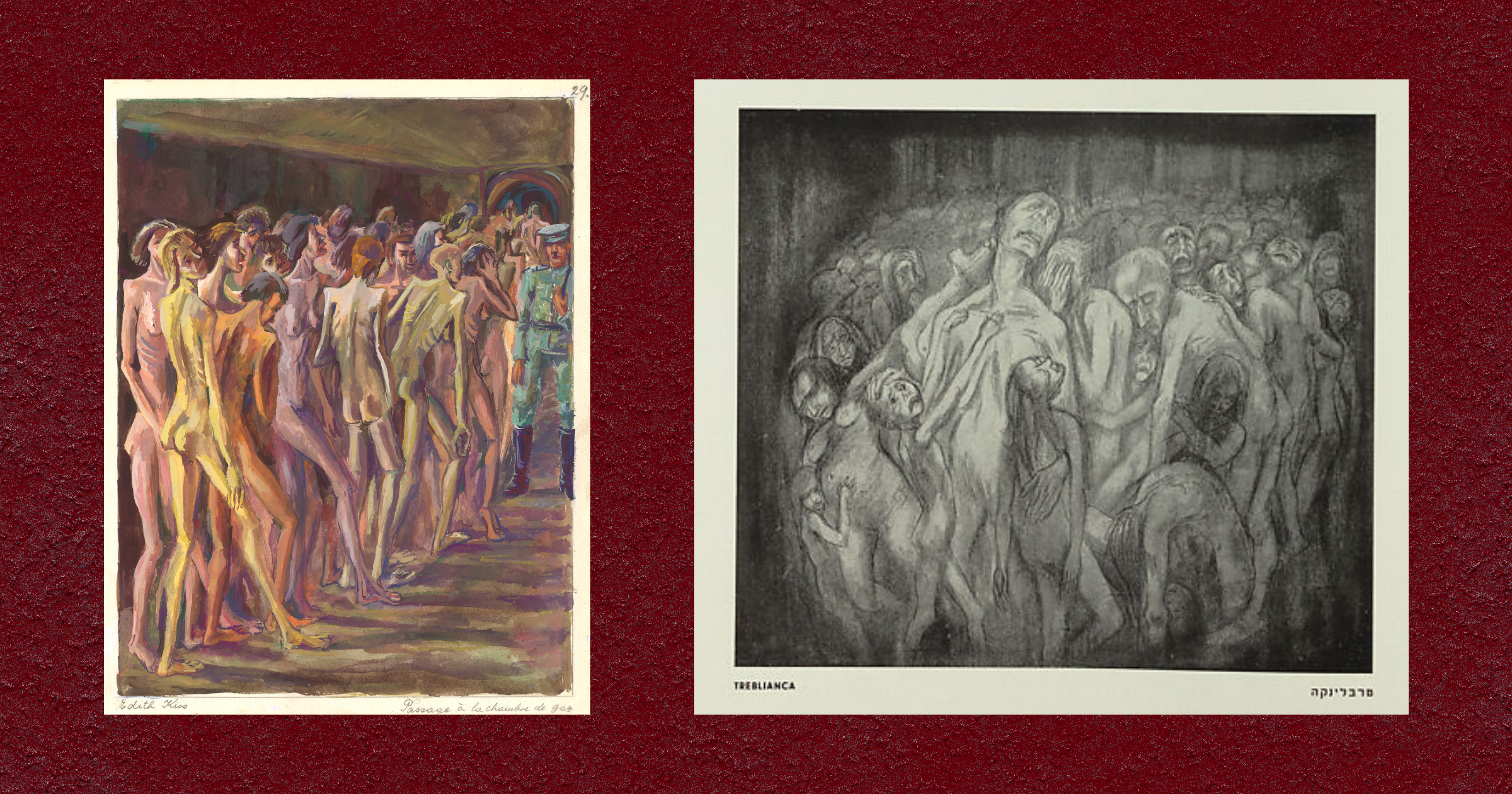

For example, Hungarian artist and sculptor Edith Ban Kiss, who survived Ravensbrück, painted a series of 30 colorful gouache paintings in 1945 shortly after her liberation. Titled “Deportation,” they were first displayed in Budapest in September 1945. Today, the series is part of the archives of the Ravensbrück Memorial and Museum in Germany.

Two of her gouaches appear in the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute exhibit. Stark and direct, one depicts an entangled group of women crammed into a cattle car. The other shows the backs of skeletal, naked women, their ribs slashes across emaciated torsos. A German soldier watches dispassionately as some of the women clutch their heads or cry out while moving forward.

In her research, Perry found that a number of the illustrations depicted what she called a “gendered form of abuse.” Many of the artists repeatedly created scenes in which a Nazi soldier or official inspects or beats naked women.

“There was a form of sexualized violence and more invasive forms of torture endured by women,” Perry said.

Rozenstrauch’s book from 1945 is a focus of the exhibition. The original was too fragile to travel from its home in Yad Vashem, so a facsimile of the book is displayed in the center of the exhibition room. Rozenstrauch married and changed her name to Naomi Judkowski after the war and became an architect in Israel. The display also includes an explanation of the book’s role in the Eichmann trial. Submitted as legal evidence, illustrations from the book were used as visual proof accompanied by survivor testimony.

“This book is one of the more interesting elements of the show,” said Lisa Fishbayn Joffe, director of the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute.

“As a lawyer by training, I found it to be an amazing intersection of the struggle for justice and these women’s creativity.”

Eichmann’s 1961 trial, televised and broadcast around the world, ushered in an era of public interest in and access to survivor testimony, Perry said. The Hadassah-Brandeis Institute exhibition demonstrates an even earlier era of public access: in the early postwar years, with survivor-led exhibitions in Hungary, Germany and Italy—many of them organized by women.

Perry, who specializes in the visual culture of the Holocaust, asserts that these works can be seen as precursors to the modern graphic novel, and its sibling the graphic memoir. That genre is perhaps employed most effectively and famously to explore Holocaust themes in Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus.

There is a “recognition that this is a medium that allows for greater accessibility and larger audiences,” she said. “Spiegelman himself dubbed this evolving genre as ‘a way to sweeten a bitter pill.’ ”

The exhibition’s poster shows a photograph of artist Lea Grundig’s hands drawing a woman’s face distorted by pain, an emblem of these women’s attempts to convey the unthinkable. Grundig, who protested the Nazi occupation of Dresden through art, was imprisoned by the Gestapo for two years before escaping to Mandatory Palestine in 1940.

On view are expressionistic ink drawings from Grundig’s 1944 booklet In the Valley of the Slaughter. One depicts a mass of women who appear to support one another as they flee German soldiers. The booklet was published in Tel Aviv and copies of the original publication are at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and The Weiner Library in London as well as other archives.

Indeed, Perry uncovered “image albums” in major Holocaust archives, such as Yad Vashem and the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, and also in smaller collections, such as the Hungarian National Museum, the Illinois Holocaust Museum and the Ravensbrück museum, as well as in private holdings.

The rediscovery of these female artists and their artwork, she said, broadens “our cultural imagination of the camps, which mostly has been created by two distinct groups: perpetrators and liberators.” It also challenges the assumption that photographs were the only immediate visual records of what had happened.

Haunting and powerful, the show’s graphic narratives speak to the urgency of self-representation and the importance of showcasing women’s accounts of the Holocaust.

Judy Bolton-Fasman is the author of Asylum: A Memoir of Family Secrets.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply