Books

REVIEW: ‘The Dressmaker’s Mirror’

The Dressmaker’s Mirror: Sudden Death, Genetics, and a Jewish Family’s Secret

By Susan Weiss Liebman (Rowman & Littlefield)

Long before his co-discovery of DNA, molecular biologist and geneticist James Watson made an assertion that still stands up. “We used to think that our fate was in our stars,” he said. “But now we know that, in large measure, our fate is in our genes.” Indeed, hardly a day goes by without the announcement of a new discovery connected to our genes that can profoundly affect the way we live.

In her part-memoir, part-medical investigation The Dressmaker’s Mirror, Susan Weiss Liebman, a geneticist and former biology professor at the University of Illinois Chicago, recounts the discovery that gave her the key to unraveling a genetic mystery within her own family. The story begins with the sudden death in 2008 of her pregnant 36-year-old niece, Karen Rothman Fried, which prompted Liebman to investigate the tragic losses that had haunted her Jewish family for generations.

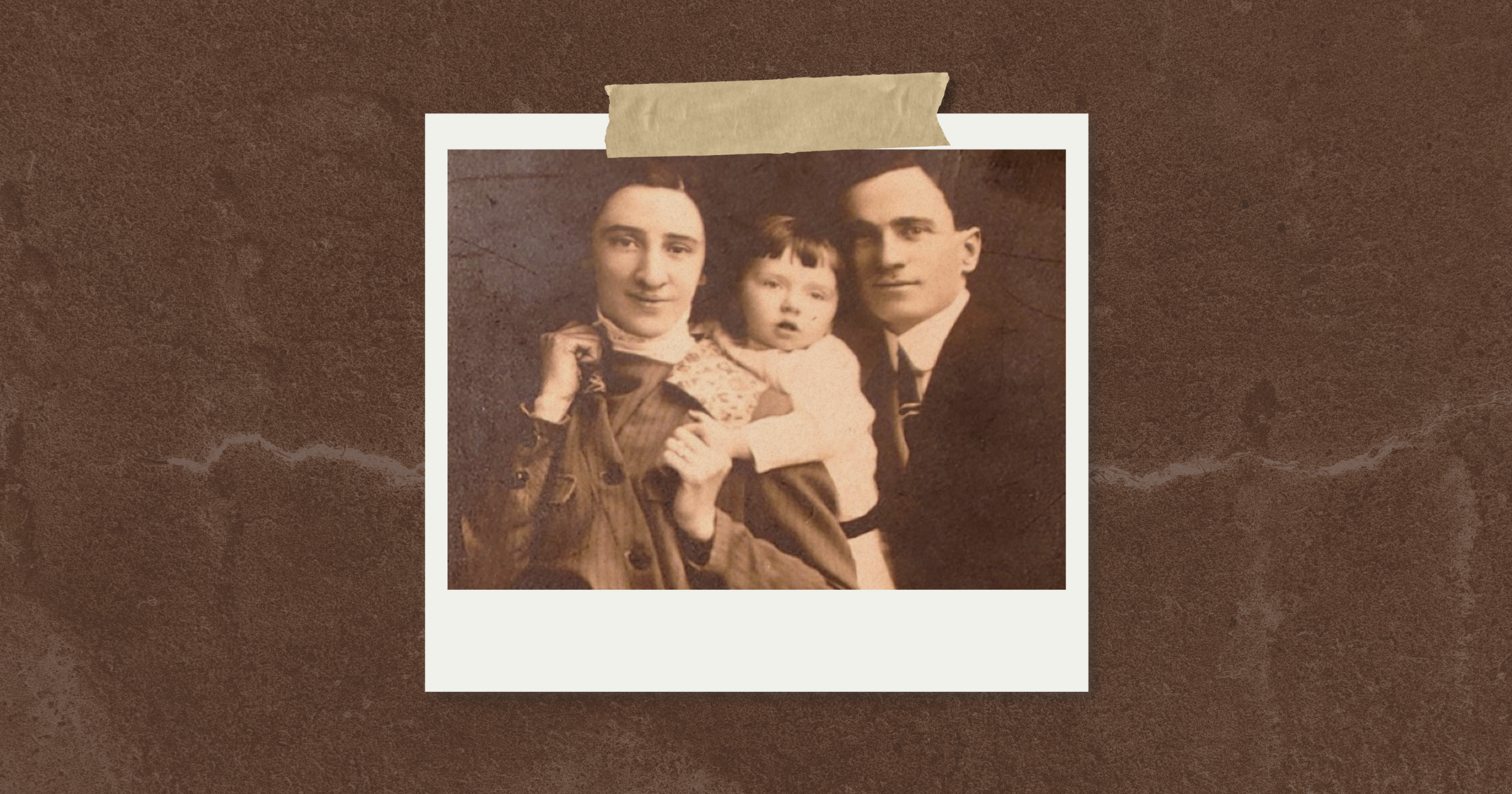

Liebman takes readers back to 1916 and the death of her 4-year-old uncle, Eugene Weiss, believed to have been killed when a massive standing mirror fell on him. Liebman had first learned of Eugene at age 6, after discovering a photograph of the boy. When she asked about it, she writes that her father simply replied: “That’s my brother…. His name was Eugene…. I didn’t know this brother because he died before I was born.”

As an adult researching her own genetic background, Liebman combed through family documents and uncovered a shocking discrepancy: His death certificate stated that Eugene had succumbed to congestive heart failure following a five-day hospital stay. Yet her grandparents had always claimed that the large mirror used by her grandmother, a gifted seamstress, in her home-based dressmaking business was the cause of their son’s death.

Liebman also found out that her family had lived in Carbondale, Pa., at the time of Eugene’s death, and that his hospitalization was widely reported in the local news. Indeed, her grandparents, insistent on hiding their son’s death, decided to move to Scranton, about 20 miles southwest of Carbondale, after Eugene died.

In the book, she reaches further back in time, tracing her family’s start in the United States. In 1906, her paternal great grandfather fled a wave of pogroms in Kharkiv, today the second-largest city in Ukraine, and brought his family to Pennsylvania, where they shortened their last name from Weissman to Weiss. Meanwhile, her maternal grandfather had left the hardships and antisemitism of Czarist Russia for New York City, where he became a successful dentist.

Liebman brings her story into the modern era as she investigates her niece’s sudden death. On the 28th yahrzeit of Liebman’s father, who had died of a heart attack, Karen Rothman Fried, newly married and pregnant with her first child, collapsed and died while dining out with her husband. The autopsy indicated no foul play and no aneurysm.

However, further study of Fried’s heart, requested by the New York City coroner, revealed that she had died from dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), an enlarged and weakened heart.

After obtaining the autopsy report, Liebman discovers that Fried’s enlarged heart was the result of a genetic mutation—and that Diane Rothman, Fried’s mother and Liebman’s older sister, had unknowingly passed the fatal gene to her daughter.

“A mutation that could attack and kill members of my family at any time seemed to be on the loose,” Liebman writes, “so I decided to hunt down the killer before more of us were picked off in God’s cruel game of Russian Roulette. My sister was an enthusiastic partner in this search. We were both desperate to protect our children and grandchildren.”

In 2016, after her sister Diane had been diagnosed with and died from complications of DCM, and with the help of researchers and genetic cardiologists, Leibman was finally able to identify the culprit behind generations of family tragedy. They identified the 3791-1G>C mutation in the FLNC gene, which is associated with a higher risk of heart defects among Ashkenazi Jews.

The mutation appears in roughly 1 in 800 Ashkenazi Jews and in no other ethnic group. Such specificity and high frequency indicate that the mutation developed and spread over centuries within the insular, intramarried Jewish community.

Liebman’s journey of discovery has made her a fierce proponent of genetic screening, which assesses an individual’s risk of developing or passing along a genetic condition, as well as genetic testing, which identifies specific mutations. In the book, she writes about the broader implications of widespread genetic screening without a clear family history, discussing concerns about the limited clinical resources, employment discrimination and potential denial of life insurance. Yet she emphasizes the positive: Genetic counseling is relatively inexpensive, and the knowledge gained by screening could help medical professionals take preventive actions or make earlier diagnoses—intervention, she feels, that could have prevented her niece’s sudden death.

“I believe I became a geneticist, at a time when few women pursued this path, because I was destined to help understand the family illness and advocate for genetic screening,” she writes in her preface.

As Liebman suggests, genetic screening paired with appropriate, effective medical intervention can change our fates.

Stewart Kampel was a longtime editor at The New York Times.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Rebecca Block says

I attended a zoom presentation by Quesher of the Dresssmaker’s Mirror. It was very fascinating and I learned a lot. I would love to hear her speak again. Does Hadassah have plans to have her speak? It was through the magazine that I learned of the book and then I learned that Dr. Liebman was presenting for Quesher.

Thanks.