Books

Holidays

Shavuot

Jewish Unity Without Uniformity

While attending the March for Israel in Washington, D.C., on November 14, 2023—one of the largest gatherings of American Jews in modern history—I closed my eyes for a second and imagined how it might have felt for our ancestors standing at the foot of Mount Sinai.

Back then, according to the Book of Exodus, hundreds of thousands of Israelites, hailing from diverse tribes, came together for a collective purpose. These individuals knew in their hearts that this moment demanded their presence. Some arrived at this moment looking for hope, others sought inspiration and still others yearned for comfort. Perhaps for most, it was merely a longing for a sense of belonging and camaraderie. As they stood shoulder to shoulder, forming one enormous entity, their diversity faded into the background and their hearts and souls were interwoven. At this moment, they were not Jews or Hebrews, but rather Bnei Yisrael, the united offspring of Israel, bound together as one family unit. Standing in this diverse yet unified crowd, they realized that “Children of Israel” was more than just a name—there was a sacred purpose behind it.

Now it was my turn. Standing on the National Mall in Washington, surrounded by close to 290,000 people, primarily Jews, coming from all corners of the earth and from across the political and religious spectrum, shook me to my core. I was thrown back 3,300 years to Sinai. Yet it wasn’t a dream. On that day in Washington, the Children of Israel again stood united.

But why did it take a massacre of Jews on October 7, 2023, the deadliest day for our people since the Holocaust, to bring us together for the first time in some of our lifetimes?

The following month, I traveled to India on an Entwine Insider Trip of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. Entwine allows participants to explore diverse communities and global Jewish issues, emphasizing personal responsibility. In India, our group was enriched by the presence of the Jewish Youth Pioneers (JYP), a group of young Jewish adults who play a vital role in sustaining the local community.

As we learned about their unique Jewish experience, we found countless parallels in our traditions and customs. It was heartening to realize that while I’m baking challah, lighting Shabbat candles, praying at synagogue or engaging in discussions about Israel, my friend and past president of JYP, Sharon Samuel, is doing the very same thing in India.

“Being Jewish in India, we don’t know many other Jewish people, and many people in India don’t know who we are,” Sharon told me. “After the October 7 massacre in Israel, people around the world were reaching out to offer security for our Jewish community. It’s comforting knowing that someone Jewish in America or Israel is looking out for us just because we are Jews.” This is the essence of Jewish peoplehood: a collective commitment to stand by fellow Jews globally, and not just in times of tragedy. It is driven by the principle of ahavat yisrael—the love for our people.

The Book of Exodus tells of Moses’ ascent to the summit of Mount Sinai, where God commands him to wait, as he is about to receive the tablets containing the Ten Commandments. Yet Moses’ ascent would offer something additional. He received a profound gift atop that mountain: a sacred and unforgettable image of Bnei Yisrael in a panoramic view that encapsulated the essence of the Children of Israel. He witnessed the 12 tribes of Israel standing before him, arranged by family, each appearing so different from one another, yet all standing side by side, revealing the beauty of the Jewish people even with its differences. Our unique strength is precisely that: unity without uniformity.

Moses; his brother, Aaron; Aaron’s two sons, Nadav and Avihu; and the 70 elders of Israel ascended, but only Moses went to the top. The others were left behind after being given strict instruction from Moses: “Remain here for us until we return to you” (Exodus 24:14).

Now imagine if Moses had appealed to God for Aaron, Nadav and Avihu to join him atop Mount Sinai. All of them could have had the opportunity to witness the breathtaking panoramic view capturing the essence of the united, yet diverse, Children of Israel.

A medieval rabbinic legend portrays Moses and Aaron walking up the mountain with Nadav and Avihu walking behind them. Nadav and Avihu remark to one another, “When these two elders die, we will rule over the congregation in their place” (Yalkut Shimoni 361).

Virtual Event: Young Zionists Take Up the Fight

Join us on Wednesday, June 18 at 7 PM ET when Hadassah Magazine Executive Editor Lisa Hostein moderates a panel discussion with young women speaking up for Israel today as well as some leaders working with Gen Z communities.

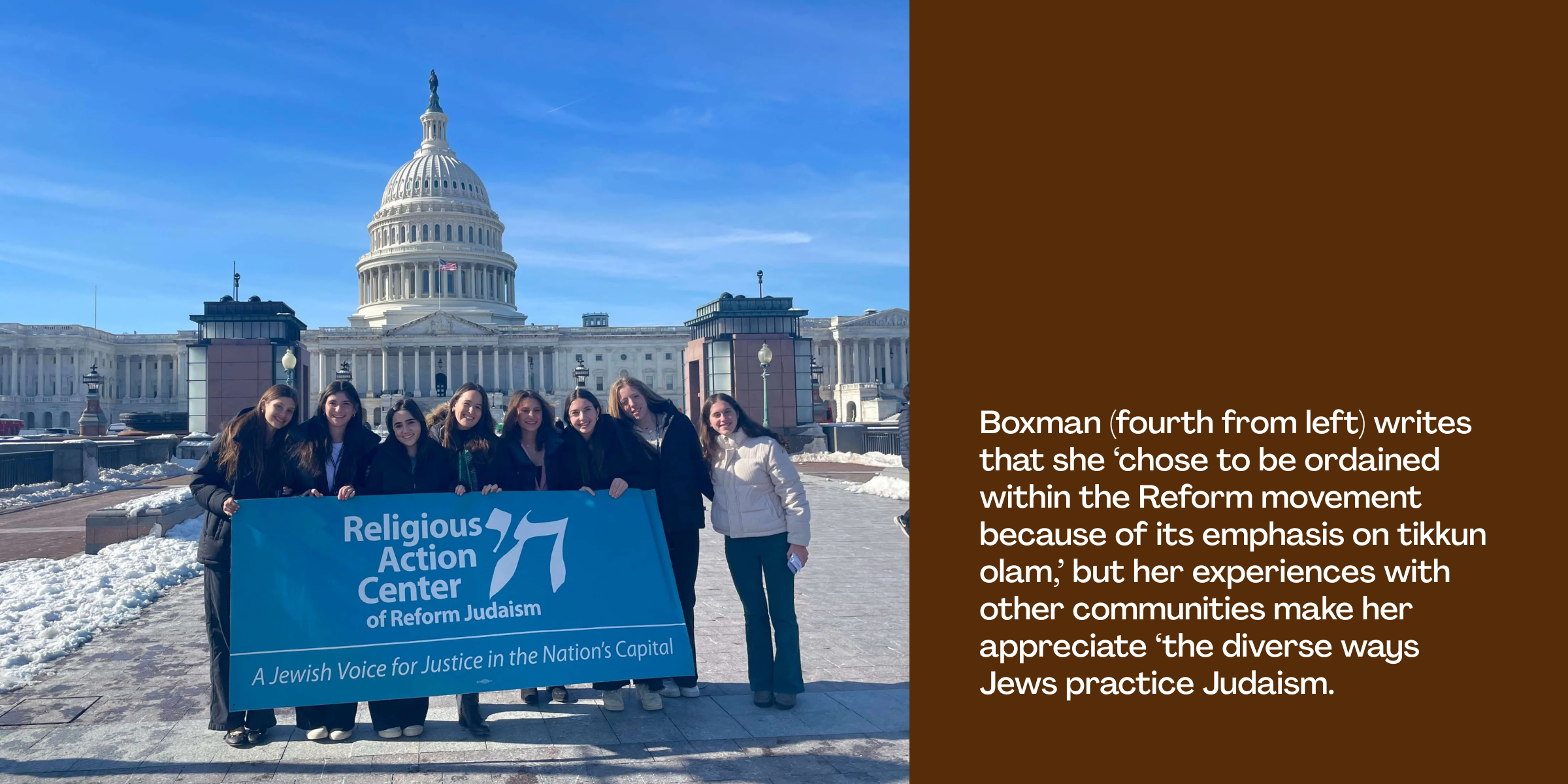

Guests include Yocheved Ruttenberg, who founded the 40,000-strong Facebook group Sword of Iron-Israel Volunteer Opportunities in the immediate aftermath of October 7 and who has been named to Hadassah’s 2025 list of 18 American Zionist women everyone should know; Reform Rabbi Ashira Boxman, who has written about the need for Jewish unity in a time of threat for Israel and Jews everywhere; David Hazony, editor of the 2024 anthology Young Zionist Voices: A New Generation Speaks Out and director and senior fellow of the Z3 Institute for Jewish Priorities; and Adina Frydman, CEO of Young Judaea, the oldest Zionist youth movement in America.

The magazine is partnering for this program with Hadassah’s Education and Advocacy Division. It is free and open to all.

Why were they not permitted to stand alongside Moses, soaking in the beauty of our diverse yet united community, thus preparing to amplify it for the next generation?

A more ancient rabbinic legend sharpens the question further, outlining two fatal sins of Nadav and Avihu, which might have been avoided had they been given a chance to stand on the mountaintop—and which are strikingly familiar in our Jewish world today. The first was the “strange fire” they brought to the altar; the second was the sin of “not having taken counsel” with one another (Leviticus Rabba 20:8).

Nadav and Avihu each brought his own fire, which seemed odd to the other. According to the legend, they brought what they were familiar with, creating a fire reflecting only what they knew and had learned growing up. Yet, in the process, each omitted essential ingredients that could have produced a more sacred fire that warmed them all. They were ignorant of how to ignite the sacrificial fire, because no one had shown them how.

Likewise, many contemporary Jewish communities—including the Reform movement of which I am a part—have mistakenly omitted some crucial ingredients in the education of the next generation, including our sacred purpose of being Bnei Yisrael.

For decades now, many liberal Jews have prioritized the mitzvah of tikkun olam—repairing the world—at the expense of other critical Jewish values, especially ahavat yisrael. We have forgotten that the latter is inextricable from the former. To repair the world without repairing oneself is to care about the suffering of others while neglecting one’s own. Mending our relationships with our fellow Jews, taking responsibility and supporting communities halfway around the world are essential.

As the verse from the Mishnah suggests, “If I am not for myself, who will be for me? If I am only for myself, then what am I?” (Pirkei Avot 1:14). Or the passage in the Shulchan Aruch, the premier halachic code from the 16th century: “Any relative should be given preference to a stranger; the poor of his own house to the poor of the city at large; the poor of his own city to the poor of other cities; and the poor who dwell in the Holy Land to those who dwell in other lands” (Yoreh Deah 251:3).

Here, we witness the intersection of particularism and universalism. However, as the sequence of these verses implies, our initial focus should be directed inward before extending ourselves outward.

“A universal concern for humanity unaccompanied by a devotion to our particular people is self-destructive,” wrote the great Reform theologian Rabbi Eugene Borowitz, “but a passion for our people without involvement in humankind contradicts what the prophets have meant to us. Judaism calls us simultaneously to universal and particular obligations.” This was the aspirational goal of the Reform movement half a century ago.

Since then, however, Reform Judaism has not conveyed adequately enough, especially to the younger generations, the importance of peoplehood and the concern for our fellow Jews.

As the Orthodox theologian Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik explained in his book Kol Dodi Dofek, the Jews in exile settled in different lands, encountered different cultures and adopted a wide array of dialects and modes of dress. In a sense, the Jewish people sprouted multiple heads. This immediately raises the question of whether such a multiheaded being truly retains a sense of unity. The test case is what happens when one head finds itself in pain or trouble; if the other heads also cry out and seek relief, then they all still belong to one whole.

Our motivation to repair the world comes from the realization that our diverse experiences hold value and have shaped each individual’s journey.

I grew up in a home that emphasized the importance of tikkun olam. I deepened this important value by attending Union of Reform Judaism camps my whole life, participating in NFTY EIE High School in Israel and being the daughter of a rabbi who chose to be ordained within the Reform movement because of its emphasis on tikkun olam.

I have also been fortunate to have had many other experiences that have taught me the value of ahavat yisrael. I attended a Modern Orthodox Jewish day school, served on the board of my campus Chabad as the social action chair, and currently I am serving as a JDC-Weitzman Fellow, which teaches the importance of caring for all our fellow Jews wherever they live. These experiences have led me toward the summit of the mountain to observe, to engage with and to learn from the diversity of the Children of Israel.

I sincerely hope Jewish leaders will develop greater tolerance and begin genuinely engaging in the richness of diversity that is our people. They can begin by appreciating the diverse ways Jews practice Judaism. When each Jew is confident in who they are, they do not need to fear those who worship differently. They need not be confined to the “strange fire” of their own denominations.

Nadav and Avihu’s other sin was not taking counsel from one another. Each brother brought his own offering without discussing it with the other. They had no desire to learn from one another. They missed an opportunity to appreciate each other’s contributions, and their inability to collaborate ultimately led to their downfall.

I recognize this danger way too often in our world today. We isolate ourselves from the rest of the Jewish world when we are unwilling to engage with perspectives different from our own. Like Nadav and Avihu’s strange fire, other people’s ideas and truths might appear unsettling, but we must push ourselves to engage with others.

By bringing future leaders up the mountain and enabling them to see the beauty that is the mosaic of our people, they might be more open to listening and learning from one another.

God said to Moses: “Come up to Me on the mountain and be there” (Exodus 24:12). As individuals in the Jewish community, we need truly to be there, even when it feels uncomfortable, even when we disagree. As we celebrate the giving of the Torah on the holiday of Shavuot, my prayer for the Jewish community is to lead with openness, to remain present with the sacred beings before us, to cultivate growth through listening and engagement, to embrace difference, to transcend judgment with kindness and to replace assumptions with understanding.

Rabbi Ashira Boxman was a member of the graduating class of 2025/5785 at the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in New York City.

This essay was adapted and excerpted from Young Zionist Voices: A New Generation Speaks Out (Wicked Son). Edited by David Hazony. Copyright © 2025 David Hazony.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply