Israeli Scene

Fermenting a Comeback

Grapevines are such delicate and beloved plants that some vintners describe them as children. Each one is unique and requires tender care as it matures. It usually takes three years until a vine’s fruit is worthy of winemaking. Even mature vines require constant attention. They must be pruned in winter so they can grow new shoots in spring; monitored and tweaked through early summer to ensure ideal grapes; and harvested at just the right time in late summer or early fall depending on the soil, the weather and even the angle of the sun.

So, when war came to northern Israel in October 2023—bringing with it intense exchanges of fire with Hezbollah in Lebanon, massive Israeli troop movements and blazes sparked by rockets and other weaponry—it wreaked physical and economic havoc on the local wine industry. Vineyards were scorched, tourists disappeared and many of the workers either fled the region or were unable to reach the fields because of the dangers.

“About one-third of our vineyards were burned in fires caused by the war,” said Raz Garber, manager of direct sales at Galil Mountain Winery, whose winemaking facility and visitor center at Kibbutz Yiron is located less than 600 yards from the Lebanon border. “It was very difficult to deal with. The vintners would run with hoses to put out the fires themselves. Some vines could be salvaged, some not.”

A number of the vines that survived were nevertheless rendered useless because their grapes were fouled by smoke and excessive heat.

“Last year’s harvest, in summer, yielded many grapes that were unusable because they smelled like smoked meat,” said Garber, whose winery produces about 1 million bottles per year, including syrah, merlot, rosé and a variety of white blends. “It’s very heartbreaking because there’s great significance to aged vines,” he added about some of the vines that were lost. “Aged vines yield fruit that is higher quality, more concentrated. It’s like losing an investment. You invest 20 years in a vine and then it’s gone. It’s very painful. Rehabilitating the vineyards will be a long-term process.”

The war that began with the Hamas massacre on October 7, 2023, has taken a tremendous toll not just on southern Israel but on the North, too. More than 110 Israeli soldiers and civilians were killed in northern Israel after Hezbollah began its own attacks the day after Hamas’s rampage, and at least 50 more soldiers were killed during Israel’s ground war in Lebanon in fall 2024. Over 68,000 Israelis from the evacuation zone in the North were displaced from their homes during the war; by early June of this year, six months since the ceasefire with Hezbollah, approximately 50 percent had yet to return, by many accounts.

The harm to Israel’s northern wineries is not a mere footnote. Nearly 50 percent of the country’s vineyards are located in the North, with some 4,000 acres in the Galilee and slightly less in the nearby Golan Heights. (The Galilee is the northern part of Israel adjacent to Lebanon; the Golan, which Israel captured from Syria in the 1967 Six-Day War, is further east and borders Syria.) Wineries in the Golan were largely unharmed because of their relative distance from Lebanon. The northern Galilee was hit hardest.

“Wine is a significant sector for the region,” said David Chapot, author of a recent report by ReGrow Israel, a project of the Israeli agricultural nonprofit Volcani International Partnerships, which assessed the war’s impact on agriculture in northern Israel. “It’s not just about the vines that were destroyed; it’s about the processing, the wineries, agrotourism. There are all these ancillary sectors around them, all of which are dependent on this sector and all of which have been pummeled by this war.”

Overall, Israel has around 300 wineries, producing about 40 million bottles annually, though it is too soon to know total numbers for 2024 vintages. Before the war, Israel exported close to $57 million worth of wine per year, comprising roughly 20 percent of the country’s wine production. A drop-off in exports was avoided in 2024 thanks largely to increased sales to the United States—and despite a decrease to sales in Europe, where anti-Israel sentiment is more pronounced.

In Israel, the war exacted a toll both on production and on domestic consumption, particularly in the early months when many restaurants were closed and demand was dampened. While Israeli demand for wine has recovered, wineries in war-affected areas are still far from fully operational.

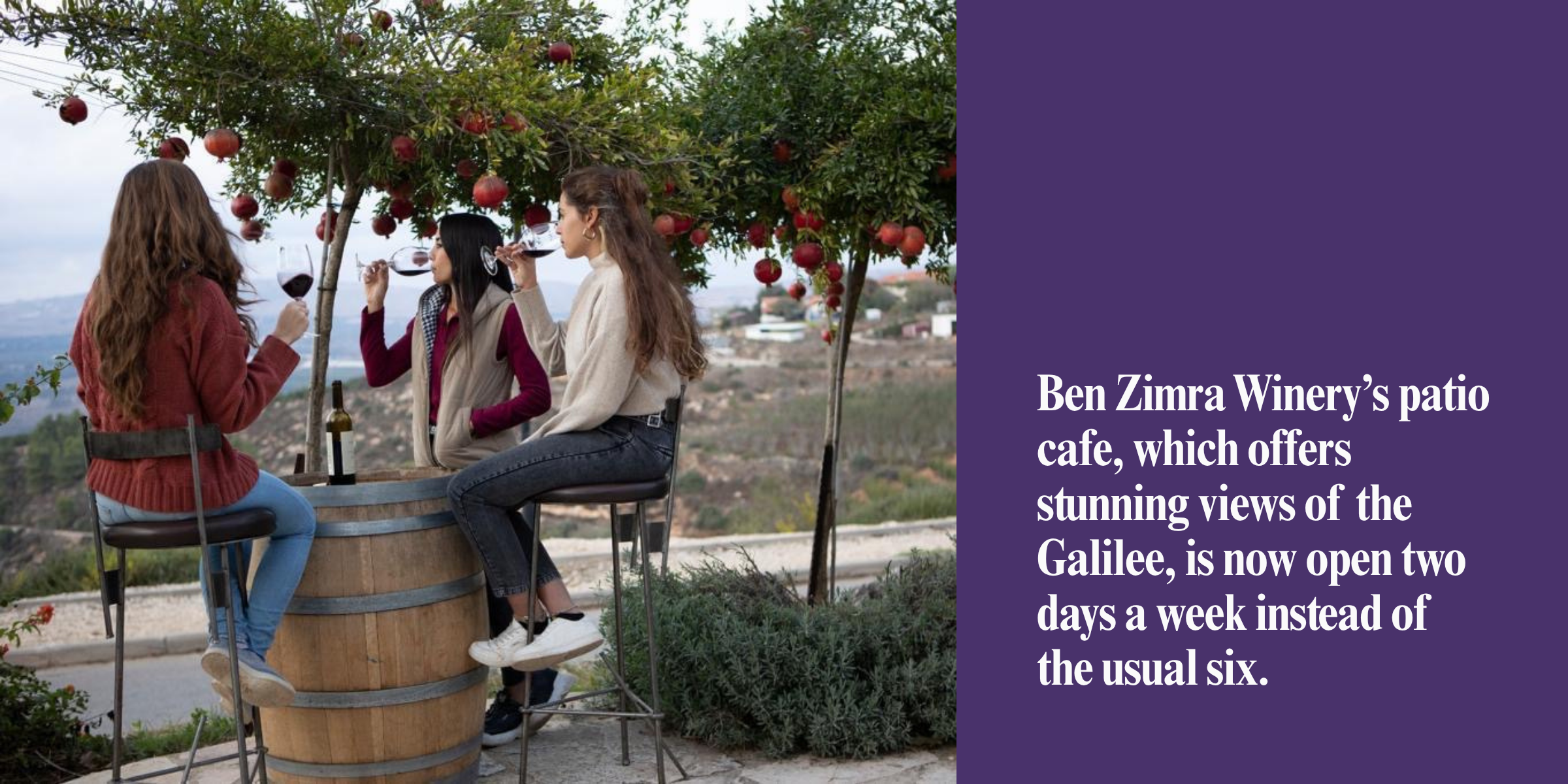

Ben Zimra Winery, which produces about 50,000 bottles annually, including cabernet, syrah, chardonnay, sauvignon blanc and others, takes in 50 percent of its revenue from its visitor center, according to manager Hila Buju. Visitors come for tastings, tour the vineyard on golf carts and enjoy cheese and wine in the courtyard. The visitor center’s patio cafe, set amid olive trees, grapevines and fragrant sage bushes, offers stunning south-facing views of the Galilee’s rolling hills, including rival vineyards.

But for a year and a half, Buju said, “the visitor center was closed, and even now it takes time to get things going again.” Due to staffing shortages, the center is open just two days a week, instead of the six it was open before the war.

To make up for lost tourism revenue, the winery focused extra effort on remote sales and harvested fewer grapes so it wouldn’t have more inventory than it could sell. Ben Zimra uses only 5 to 7 percent of the grapes it harvests; the vast majority is sold to other wineries—a common practice.

Israeli labels regularly snag prizes at the Decanter World Wine Awards, the largest and most influential international wine competition. While many of the top honors for Israel go to the country’s largest wineries in the center of the country, including Barkan, Carmel and Teperberg, a number of well-known brands from the North also have earned international renown, such as Dalton, Recanati, Tabor and Golan Heights. Dalton, located close to the Lebanon border, took particularly heavy fire during the war, with over one-third of its vineyards suffering damage, according to the winery.

But it is smaller operations that have been most affected. Keren Alon, who runs the Ancient Safed Winery

along with her husband and eight children, said the war pushed them into near poverty.

“We and many other businesses in Safed made a good living from foreign tourists. Then came the war, and tourists stopped coming completely,” Alon said.

Her adult children visited on their days off work to help, and the business stayed afloat through remote sales, including to customers overseas. Her husband, Moshe Alon, spent most days working in their vineyard, where there is no bomb shelter or siren to warn of incoming fire. He was saved once purely by chance when a rocket struck the vineyard on a rare day when he wasn’t there, Alon said, and their land suffered only minimal damage.

Alon said she kept the visitor center open during the war just to stay sane, often welcoming off-duty soldiers in the area. “Fighters came to us on their days off, including air force officers,” she said. “It helped because we didn’t go bankrupt, but it’s very, very hard.”

The government has provided some assistance to businesses impacted by the war, but getting the funding, which typically only covers some losses, takes time. The level of assistance varies depending on a host of factors, including whether the business was in the official wartime evacuation zone.

There’s some hope that Safed will see more Israeli tourists this summer, but as long as Israel is at war, there’s little optimism that foreign tourists will return anytime soon.

Until the ceasefire with Hezbollah took effect in late November 2024, northern Israel sustained over 9,000 direct hits by missiles, rockets and drones. Fires caused by explosions scorched about 110 acres of vineyards, and another 60 or so were left to wither because they are located in restricted military zones. Some of those are not expected to survive. Replanting destroyed vineyards will cost an estimated $3 million, according to ReGrow Israel.

Avivim Winery, in the border town of the same name, was hit by rockets four times—destroying 300,000 bottles and heavily damaging its cellar, facilities and visitor center—and prompting its owners, according to one local vintner, to shut down. (Avivim Winery did not respond to inquiries for this story.)

Galil Mountain Winery’s production facility was spared such a fate because the Israel Defense Forces took up a position on a nearby border hill early on, according to Garber, the direct sales manager. On a recent visit to the winery, which is co-owned by Kibbutz Yiron and Golan Heights Winery, the largest producer in northern Israel, blooming wisteria in the garden cafe below the visitor center’s deck made for an idyllic scene in a space that before the war had been a magnet for weddings and other events.

Before the war, visitors would pack the winery on Fridays for brunch and a full tasting menu prepared by chef Almog Sabag. Now the visitor center offers just tours, wine tastings and a limited cheese menu. The big summertime parties and late August grape harvest festival won’t happen this year.

“We need permission for events from IDF Home Front Command and the police, and we haven’t gotten that,” said Bat El Yehudai, manager of Galil Mountain Winery’s visitor center. “Everything is up in the air because of the security situation.”

Even though about 30 percent of the winery’s eight vineyards were destroyed during the war, the business was saved by a surge in wine orders from Israelis and Jews worldwide.

“What helped us make up the loss was the insane solidarity of Israeli society, which sought ways to support businesses like us, whether in frontline communities in the North or the Gaza envelope,” Garber said. “We felt a huge embrace, especially from Jews in the United States and Canada. In Europe, we saw a huge decline.”

Yitzhak Cohen, who owns a boutique winery in the picturesque town of Ramot Naftaly, located on a mountain ridge just a couple of miles from Lebanon, said he was able to sell out his 2024 stock of 15,000 bottles of reds and whites also thanks to Israelis motivated to support businesses impacted by the war. The missing piece was visitors to the Ramot Naftaly Winery.

“Our visitor center was completely dormant for the entire war,” Cohen said.

His home is right behind the visitor center and wine cellar. He grows most of his grapes on four acres in the nearby Kedesh Valley, but he has a small vineyard in his backyard along with a smattering of fruit trees and a chicken coop. As we spoke, a pair of men inside the winery were busy bottling barbera, a red variety with origins in Italy. Cohen said he was the first to bring it to Israel.

“I built this winery out of love and passion for winemaking,” said Cohen, who produced his first bottle in 2003. “Working here is my retirement.”

Another family business in the northern Galilee, Adir Winery, produces 350,000 bottles per year of reds, whites and dessert wine in addition to milk and cheese from its dairy. The only direct war damage it sustained was a vineyard fire that destroyed about one acre, but the war nevertheless has hit hard.

CEO Yossi Rosenberg has been serving in military reserve duty nearly nonstop since the conflict began, and it’s been difficult managing the winery remotely. When well-meaning people reached out to invite Adir Winery to join sales fairs designed to help war-impacted businesses, neither Rosenberg, who was busy with combat, nor his brother, who was needed in the vineyards, could attend.

Because the family’s hometown, Kerem Ben Zimra, is located just beyond the government-designated evacuation zone within two and a half miles of the Lebanese border, the Rosenbergs didn’t qualify for temporary relocation funding, so they stayed put. Visitors, however, stayed away, and the winery that in normal times hosts workshops, meals and an annual fall harvest festival took a significant financial hit.

Speaking by telephone while on deployment, Rosenberg said his work in agriculture is no less critical to Israel’s future than his service as a soldier.

“Agriculture is Zionism,” said Rosenberg, whose son is also an IDF soldier fighting in the war. “Settlement of the land without agriculture isn’t full settlement, in my opinion. There’s nothing greater than agricultural work to connect you to the land.”

Uriel Heilman is a journalist living in Israel.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply