Books

Health + Medicine

The Jewish Self-Help Books We Desperately Need

When Levi Shmotkin was an 18-year-old student at Yeshiva University, he found himself sinking into feelings of negativity and insecurity. He described the experience as a kind of “black water” that enveloped him and made it difficult to focus on his studies, but he was never formally diagnosed with depression or anxiety.

Searching for relief, Shmotkin turned to the writings of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the revered leader of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement, known as the Rebbe. During his lifetime, Schneerson penned tens of thousands of letters to people seeking guidance on issues ranging from loneliness to overeating, many of them available through Chabad resources.

Those letters, Shmotkin said, helped him shift his mindset and rediscover a sense of hope. About a decade later, as an educator and rabbi living in Brooklyn, he decided to share that wisdom more broadly in his book, Letters for Life: Guidance for Emotional Wellness from the Lubavitcher Rebbe.

Reflecting on Jewish resilience through difficult times, Shmotkin said in an interview that what held Jews “together were the texts that we carried. It’s empirical to say that there is value in this ancient wisdom.”

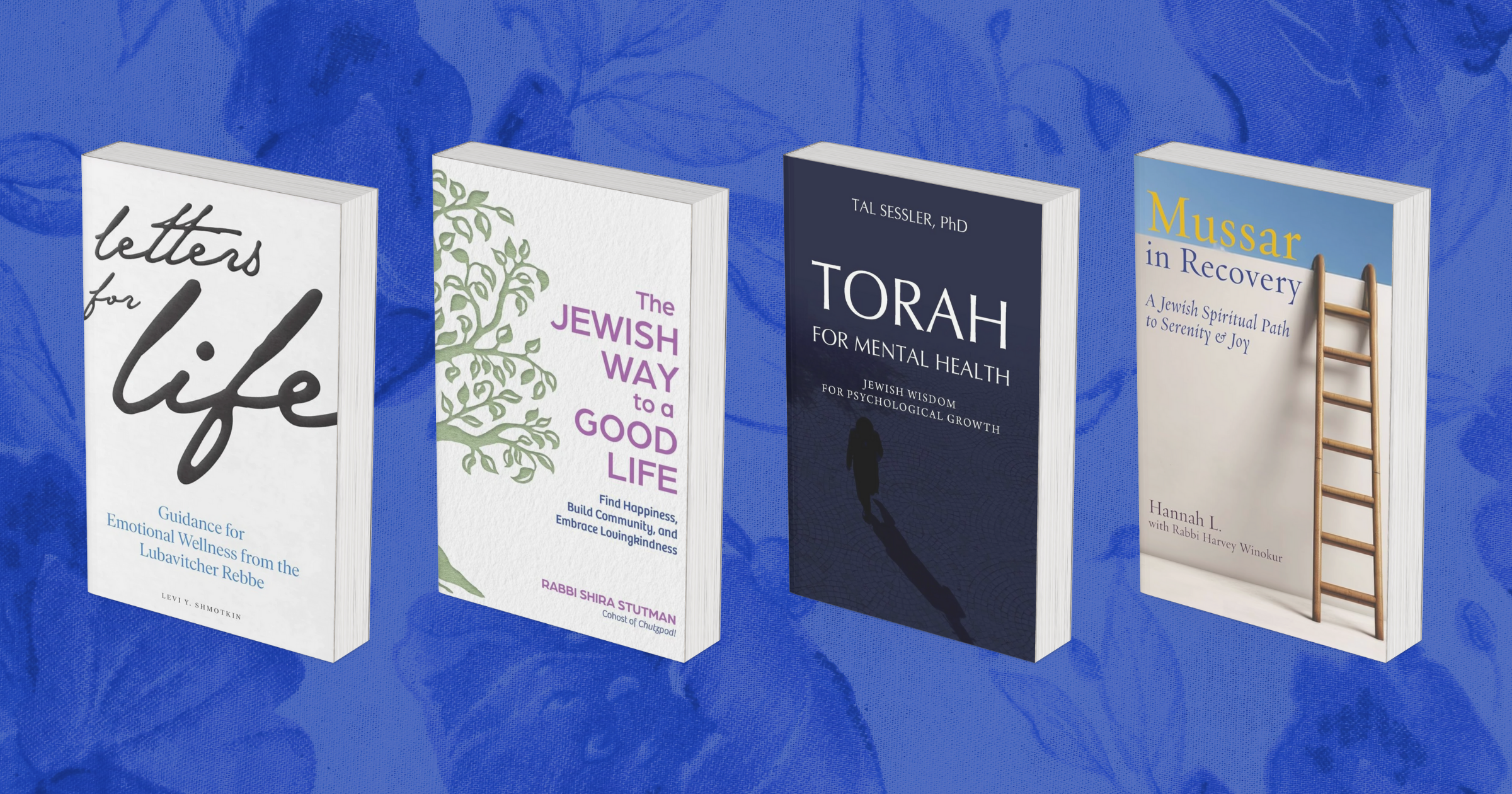

For generations, Jews have turned to spiritual and rabbinic texts for help navigating contemporary challenges. A recent wave of books continues that tradition, including titles such as Letters for Life, The Jewish Way to a Good Life, Mussar in Recovery and Torah for Mental Health. Their authors use Jewish sources to offer time-tested pathways toward meaning, strength and inner peace, with an emphasis on community. Along the way, they also clarify that what many today call “self-help” has deep Jewish roots.

As he explains in his prologue, Shmotkin focuses on the Rebbe’s letters that give practical, actionable recommendations on living a good life. Divided into two parts—“Essentials for a Healthy Life,” which focuses on building beneficial habits, and “Overcoming Darkness,” on combating negative emotions and behaviors—the book has inspired Orthodox study groups across the country. But the simple advice contained in the letters Shmotkin shares is universal.

For example, a section that unpacks the social benefits of getting involved in one’s community discusses the story of Soviet refugee Taibel Lipskier, who fled to the United States in 1947 and later sought the Rebbe’s guidance for her persistent sadness. His response was disarmingly direct: “Go to as many weddings as possible and dance—and inspire other people to dance, too.”

Shmotkin cites Lipskier’s grandson, Rabbi Y.Y. Jacobson, who said the Rebbe’s prescription not only lifted his grandmother’s spirits and those around her, it also integrated her more deeply into her community. “She lived in Brooklyn, where many young women getting married had little or no family present,” Jacobson said of the Crown Heights Chabad community, which was home to many women impacted by the Holocaust or whose families had rejected them because they had become observant. “My grandmother would show up and dance—sometimes for hours—with the bride and her friends, bringing immense joy to the wedding.”

Rabbi Shira Stutman likewise focuses on joy in The Jewish Way to a Good Life: Find Happiness, Build Community, and Embrace Lovingkindness. Stutman explains that in Judaism, joy is inseparable from community. “The notion of being happy in your ivory tower, all alone—that’s entirely foreign in the Jewish tradition,” Stutman, senior rabbi of Aspen Jewish Congregation, a Reform synagogue in Colorado, and co-host of the podcast Chutzpod!, said in an interview.

Across 10 chapters, on topics from ahava, love, to Shabbat, in which she discusses the idea of resting, Stutman explores Jewish values through personal anecdotes and traditional texts and customs, showing how core Jewish ideas balance individual fulfillment with communal connection.

She, too, visits the topic of dancing at weddings, in her chapter on simcha, happiness. Stutman recalls the exuberant circle dance at her own wedding and contrasts it with the more solitary “first dance” tradition common in American ceremonies. “Happiness centers the community; the self comes second,” she writes.

“The Jewish idea of happiness is one part mosh pit, one part sweat—but all parts joy and celebration together,” Stutman said.

A fusion of emotional wellness and connection guides Rabbi Tal Sessler’s Torah for Mental Health: Jewish Wisdom for Psychological Growth. Sessler, the rabbi of Temple Beth Zion, a Conservative congregation in Los Angeles, has long seen the “therapeutic component of rabbinic life” as essential to his work in providing spiritual care.

Sessler’s book, composed of accessible mini-chapters, blends rabbinic and Jewish teachings with reflections from secular thinkers and practical advice. Topics range from dealing with anxiety regarding politics to gratitude and mindfulness.

“The first two words that Jews are encouraged to say upon waking are modeh ani—‘grateful am I,’ ” Sessler writes in one chapter. “Gratitude isn’t just a feeling. It’s a practice.”

In addition to encouraging readers to cultivate gratitude daily, whether through prayer or journaling, he notes that modern research echoes Jewish tradition—that gratitude and happiness are deeply intertwined.

“I always recite my own gratitude list,” he writes, explaining how the practice restores his emotional equilibrium as he himself wrestles with political turmoil. “I created this daily ritual, which I am very strict and meticulous about, because we human beings are prone to ‘negativity bias’—a notorious human disposition to focus more on that which is lacking and not working in our lives.”

For Hannah L., a mother from Atlanta, the centuries-old Jewish spiritual practice of mussar became a lifeline when her son battled a drug addiction. And when, she admitted, she became “addicted to fixing him.”

Hannah (she omits her last name in keeping with the anonymity in recovery communities) found support through Al-Anon, a sister organization to Alcoholics Anonymous designed for loved ones of addicts. While the experience was valuable, she decided to seek a Jewish framework to explore the principles in the recovery program and discovered mussar, a spiritual discipline focused on cultivating character and ethical behavior that today has found resonance with Jews of all kinds.

Together with Harvey Winokur, rabbi emeritus of Reform Temple Kehillat Chaim in Roswell, Ga., as well as a facilitator for The Mussar Institute, she co-authored Mussar in Recovery: A Jewish Spiritual Path to Serenity & Joy, a book that weaves Jewish ethical teachings with the 12 steps in recovery programs.

“When we view ourselves through a mussar lens,” they write, “we see that we are simply human—not uniquely bad.”

Hannah emphasizes that cultivating self-love and self-acceptance is essential—especially for those in recovery from addiction. That inward act is also mirrored in AA’s Step 4: “Make a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.”

Mussar teaches the importance of finding a healthy balance: too little self-love can lead to shame, too much to arrogance. Every person contains both a yetzer tov (inclination toward good) and a yetzer hara (inclination toward harm), Hannah explains. The goal is not perfection but balance between the two inclinations, and refining character traits through self-awareness and discipline.

Emunah, or faith, plays a crucial role in countering addiction. “Emunah is pivotal to recovery,” she writes. “All of us show up in life as imperfect beings, some more imperfect than others. Faith provides a pathway to self-acceptance and self-love.”

Shmotkin, author of Letters for Life, notes that self-acceptance and self-love are essential not only for emotional wellness but also for fighting antisemitism. The Rebbe, he said, saw love of one’s Jewish identity as a psychological anchor. When Jews assimilate too deeply into surrounding cultures, we leave ourselves vulnerable—psychologically and spiritually, Shmotkin explained.

The antidote, the Rebbe taught, was to strengthen one’s “Jewish home” through community, mitzvot and shared purpose. “When you have that,” Shmotkin said, “you’re less shaken by the antisemites. This people, this tradition, this wisdom—it’s so much greater than the ups and downs of the world around us.”

Alexandra Lapkin Schwank is a freelance writer living with her family in the Boston area.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply