Family

Feature

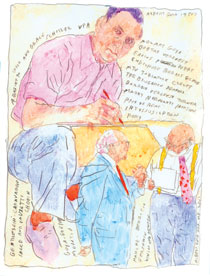

Family Matters: Good as Gold

Somehow my father scraped together $250—a fortune in 1948 and the tuition for the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art—and we drove to Philadelphia in our decrepit, rusty 1936 Chevrolet Coupe that shuckled and shook and coughed and burped.

We had an appointment; I showed my “portfolio” of imitation Norman Rockwell Saturday Evening Post covers, and I was accepted. On the way back, we celebrated in a diner, and I had eggs and fries with rye bread and strawberry jelly; when we arrived home, my mother put a quarter in the pishke.

My mother wasn’t too enthusiastic about my chosen career. “Artists starve,” she’d say. She had a lifetime of frustration from my father’s constant struggle with failed businesses. All his life, he just wanted to play piano, but he never had any encouragement or money for formal training and knew he would never have the chutzpa to make a living playing professionally. We loved when he played Yiddish melodies for us—I love klezmer to this day from listening to my father play “Bublitchki,” “Roumania, Roumania” and “Der Rebbe Elimelikh.”

So when he had enrolled his son in the art school (now called the College of Art and Design, part of The University of the Arts), he was content. My mother eventually accepted my obsession with drawing and painting and prayed I’d be able to make a living. She conceded that maybe if things as a great artist didn’t work out, I’d be able to paint signs. Aunt Sarah, Aunt Tania, Uncle Morris, Uncle Harry and Uncle Benny also thought I would starve and have to burn the furniture for heat, but they saw how well I copied those Norman Rockwell covers. And listen, Norman Rockwell made a good living, so I should be able to make a good living, too.

“You got in? Mazel tov! Mazel tov!” they said and they all gave me envelopes with a little something to help.

When I was 14 or 15, I thought Norman Rockwell was the greatest artist that ever lived. His paintings looked like photographs—what more could any artist want? His world was wonderful and clean and happy: cheerleaders and milkmen, country doctors and friendly cops, grandpops and children with rosy cheeks.

In the lunchroom during my freshman year, original artworks by the teaching staff were hung around the room. A teacher named Ben Eisenstat startled us. His paintings were very sloppy, with puddles and shmears and drippings all over the canvas; his buildings weren’t straight and his trees were orange and his faces were purple. It was very off-putting and worrisome. How could this guy teach me how to be a bigtime illustrator?

Another teacher named Albert Gold was more accessible. His figures and trees weren’t purple and orange but most of his pictures were of poor and depressed colored people who couldn’t find work and came to our back door for something to eat. And there were paintings of zaftig old Jewish ladies, like my Aunt Sarah and Aunt Pauline, having picnics in Fairmount Park on Sunday. I remember the hard-boiled eggs, the tuna fish sandwiches, the potato salad and those beautiful golden samovars that were schlepped from home. What were these guys going to teach us? When do we learn to paint beautiful women and handsome men so we’d be able to get into Ladies’ Home Journal?

Still, Gold’s paintings fascinated me. I came to the lunchroom on breaks and after classes and looked and absorbed as much as I could understand. I asked some of the teachers about him. They told me he was well known, that he had won the prestigious Prix de Rome when he was in his twenties, that his work was in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the National Gallery in London and that he was a big-deal war correspondent during World War II.

I knew nothing about the Prix de Rome, but I was intrigued when I heard his father owned a hardware store, Gold’s Hardware. So did my father—Friedman’s Hardware. I bet he hated being in that store as much as I did.

The teachers told me the walls of his home were covered with classical records and books. Okay. Aunt Tania once gave me a dollar to come with her to shul for Friday night services. So I took the dollar and bought my first classical record—“Rhapsody in Blue.” Instead of buying the Philadelphia Orchestra, I bought the version “Swing and Sway with Sammy Kaye” and his ricky-ticky band of renown. I didn’t know. Now I know.

Years later, during dinners at his house or mine, Gold would always sit at the head of the table and say, sooner or later, “Kid, tell them that ricky-ticky thing about ‘Rhapsody in Blue.’” I was always “kid,” always “kid.”

My parents were beginning to hear daily about Albert Gold. We followed his exhibits, wherever they were, by trolley car, bus, train or when my father and mother and I would get into our ’49 Pontiac and drive to Harrisburg or Allentown to see an exhibit of Gold’s work on a Sunday morning. If there was a catalog of the exhibit, I’d say, “Pop, I have to have this.”

“Don’t you have this one already?” he’d reply.

My mother said, “Why don’t you invite Albert Gold for dinner?”

“Ma, what are you talking about? He’s a famous artist. He must live in a very fancy home.”

I found out that albert gold only taught seniors, so I would have to wait three years before I could get to him. The first year, dubiously, I spent drawing from casts, sleeping through art history lectures and painting still lifes of bananas and Chianti bottles. One thing I knew was that I could no longer deal with Norman Rockwell’s All-American-MGM-gee-whiz-Andy-Hardy-ding-ding-went-the-trolley paintings of an America that never was. In the illustration classes, we never talked about illustrators. Instead, we talked about Monet and Cezanne, Gauguin and Bonnard, America’s Ashcan painters, authors, writers and composers who chronicled the 1930s and the Great Depression. The WPA engaged unemployed artists (Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Raphael Soyer), writers and composers to do what they do with no restrictions and paid them $94.90 a month. But it was Gold and his Depression-era paintings of everyday life that knocked me over. He was my hero and mentor, only he didn’t know it yet. And he wore thick glasses. So did I. Is that a connection? Why not?

I hated that first year of art school—clay modeling, lettering, anatomy and how to make a mechanical. That stuff was all right for the kids who weren’t going to make it big, but I knew I was wasting my time with this Mickey Mouse stuff. Because I was sort of shy, I wrote Gold an impassioned letter about how much I loved his work and how our fathers owned hardware stores. I stalked him in the school halls like a nut case. I even snuck in on some of his senior classes. He knew me because I suddenly showed up wherever he was, and I probably freaked him out. One day he freaked me out while I was sitting at the back of the room in one of his classes. He asked, “Does anybody know this character? Because he seems to have a predilection of being wherever I am. Who are you, kid? Do you belong in this class?”

The class turned around and looked at me, and I squeezed down into my chair. He said, “Do you have a name, kid?”

Predilection? I ran to find a dictionary. It was the first of many words known only by Gold, because I never heard anyone use them. “He must be very smart, your Albert,” my mother said. “Maybe it’s good he never came to dinner. Who could understand him?”

Later, when we became not only student and teacher but also friends, we went often to the Latimer Deli, his favorite restaurant, a few blocks from school. Sometimes it was just the two of us and sometimes we went with another student or teacher. Eisenstat went with us a couple of times. Gold and I ordered corned beef specials; I ordered mine on a toasted bagel. “A bagel?” he said. “Kid, you’re dangerous.”

Albert Gold grew up in a home where music and culture were highly valued. He was given violin and piano lessons and awarded a scholarship to the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art. His mother was more accepting than mine. I grew up in a home where culture was limited to the New York Philharmonic programs on Sunday afternoon, Reader’s Digest and “ikh hob dikh tsu fil lib.” A ubiquitous photograph of Gold’s ancestral shtetl Jews in yarmulkes and babushkas sitting uncomfortably for their portrait in the 1890s could be the exact photograph of my shtetl family in yarmulkes and babushkas.

In 1942, while I was listening to Jack Armstrong and Little Orphan Annie and making sure all our lights were off during a blackout, Gold won the Prix de Rome, which awarded him a year of painting and studying in Rome. But Uncle Sam interrupted and he was inducted into the service, one of 12 combat artists assigned to document the war and one of three war correspondents stationed in England to make a pictorial record of the war in the United Kingdom, Germany and France. While other artists painted the dramatic images of big operations, explosions and airplanes crashing, he painted troops schlepping in the mud, eating K-rations, being homesick, reading, writing home, playing cards, bivouacking and waiting.

“I was more interested in the G.I.s than…in the machinery,” he said. “I look back with affection, and I grew up, because before that my life was limited. I was a typical Jewish boy from a warm family, and here I was thrown into a world which was far removed from where I had grown up.”

After the war, he was invited to join the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art and continued to win major awards. He was selected by the Gimbel Collection to document Pennsylvania along with icons of the 1930s and 1940s such as Andrew Wyeth, George Biddle and William Gropper.

Again, while many of the artists did the big pictures—coal mining, locomotive plants, blast furnaces, the pouring of fiery molten steel into ingots, bird’s-eye views of Pittsburgh with smoke belching day and night from factories and crowded waterfronts teeming with tankers and ferries and shipbuilding—Gold paid homage to humanity. He painted a woman in an assembly line in the old Stetson hat factory sewing on a ribbon; music lovers gathered in Robin Hood Dell, a natural outdoor amphitheater, for a summer concert by the Philadelphia Orchestra; men at the Philadelphia mint weighing coins in bulk; the Eagles’ and Phillies’ locker rooms; and many versions of a unique Philadelphia New Year’s event—the Mummers Parade. He also began his 37-year teaching career.

Finally, as a senior, I was in the same classroom with Albert Gold. For this auspicious occasion, my mother put a quarter in the pishke. I was moving along, singing a song, painting and getting positive critiques, when suddenly the world stopped.

My father developed colon cancer and it metastasized. I quit school to help in our hardware store and do whatever I could to keep him comfortable. I didn’t paint for many months. I didn’t care. He died in September on my 21st birthday. I was devastated. The last thing he said to me was, “I want you to finish art school.” I ran out of his room.

If he hadn’t said that to me, I would never have gone back. I became argumentative and petulant and I didn’t always show up to class, and Gold gave me a hard time. I stayed home and painted.

The only person in my illustration class whose name I remember was Aurora Vanelli, a compliant Catholic who laughed at my jokes and berated me when I cursed. Sometime later, I was astonished during intermission at a concert when I saw Albert Gold and Aurora Vanelli walking together to their seats, hand in hand. What? My stuffy, sagacious, Jewish old man and my virtuous young classmate? My mother said, “What? There are no Jewish girls in Philadelphia?” Albert and Aurora married in 1953—after she converted. She became Ora, daughter of Abraham and Sarah. They had two children—Maddy, who teaches design at The University of the Arts, and Bob, a classical pianist and composer and zealous archivist of his father’s work and career.

When we graduated we held a student show, and I exhibited a painting of soldiers and sailors embarking on a train at the station near my home, utilizing my Albert Gold-Friedman style. Since my father died the previous September, I was left with a huge empty place inside, and my family all decided to drive up to the school to be my surrogate father. My mother, my bobba, Uncle Benny, Aunt Tania, Aunt Sarah, Uncle Morris, Uncle Harry, my cousin Ruthy and my brother and sister-in-law came to the exhibit in three cars, an astonishing caravan of support that would illuminate a wondrous night. Aunt Sarah complained about the dollar for the parking lot and was disconcerted by the naked-lady pictures. Uncle Morris said, “Ganig, missus.” And when Gold came into the room, I whispered, “Here he is.” He walked over to my painting and stood there studying it for a minute. I once told him I thought it was an affectation to stand in front of a Monet or a Hopper you’ve seen a hundred times before and pretend to study it, something you would do on a date to impress a girl, and Gold said, “You’re meshuga.”

That night he walked over to us, reared back, and said, “This is some group. Marvelous.”

I introduced everybody, and he said to my mother, now close to tears along with Aunt Tania: “Your son is estimable, and I’m certain that you know that sometimes he’s listless, a pain in the neck, but that’s alright because he’s impudent. And a little cocky.”

My mother took his hands and said, “I feel as though I’ve known you for years. I’m sorry Marvin’s father couldn’t meet you. God bless you.” My bobba also took his hands in hers. He was startled, but I think truly moved. I am sure the pishke overflowed with joy and many quarters.

A few years later, when i was working for major magazines and winning awards, Gold invited me back to give a talk at school to his illustration class. He took me out for a “swell lunch” to any restaurant I wanted to go to, but we did not have much time, so we went to Latimer for a good corned beef sandwich.

Then suddenly there was Sonny, and kisses and marriage and children, and migraines and mortgages and deadlines, always deadlines. There were dinners at my house or his house or Ben’s or Isa’s, and questions—should the powder room be sky blue or spring green…?

In February 2006, someone called to tell me Albert Gold died. There was a snowstorm, and Mahler was played at his funeral. And to this day when I paint, I can see him standing behind me, approving what I am doing, saying, “You’re dangerous, kid, dangerous.”

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Sheila Whitelaw says

What a fabulous story. Put me right in that era. I feel as though I now know Albert Gold and so, what an honour. Thank you for sharing.