The Jewish Traveler

Feature

The Jewish Traveler: Rome

When Sandra Moreschi opened the Saray Judaica shop in the Ghetto of Rome in 1992, the guidebooks hardly mentioned the old neighborhood. Now it is on every itinerary. a Along bustling Via del Portico d’Ottavia, repaved with sampietrini, the stones first used in St. Peter’s Square, are three new restaurants serving carciofi alla Giudia, the legendary local artichoke dish. Beneath the ancient portico that gave the street its name new digs have upped the area’s archaeological gravitas. Joining the tourists in the newly reconfigured Museo Ebraico are locals curious about their own history. And Moreschi is busier than ever helping customers take home a piece of that history (a sterling silver artichoke charm, for instance).

All photos by Elin Schoen Brockman.

Moreschi intended to sell mainly jewelry; fate expanded her horizons. On her first, hectic day in business, she didn’t notice the date until she rang up her first sale: October 16. Forty-nine years before, on the rainy morning of October 16, 1943, the family that had lived where her shop now stands had been among 1,021 ghetto residents dragged from their beds by Nazi troops, loaded onto trucks in front of the portico and deported to Auschwitz.

“I cried,” Moreschi said. “I felt it wasn’t right for me to be so happy on this day which is so sad. And a woman came in and asked me what was wrong. When I explained, she said I shouldn’t feel that way because, she said, ‘now in this place where one Jewish family’s light was extinguished, the light is reignited for another Jewish family for whom hope continues.’”

Moreschi, whose Roman Jewish roots date from the 15th century, decided to use her shop to preserve and share that heritage. She worked with ceramicists in Faenza and elsewhere to create dreidels, Kiddush cups and Passover sets in traditional Italian patterns. Her signaturehanukkiya features a replica of the Arch of Titus frieze showing Roman soldiers flaunting Judean captives and treasures from the Temple they destroyed—a scene that took place right down the street in front of the portico in 70 C.E.

Like her friend, Micaela Pavoncello, who built a thriving sightseeing business, she is committed to the future of this old neighborhood. As Pavoncello says, “We’re not Jews living in Rome, we’re Roman Jews. Our culture bonded with Roman culture. We never left the city since 161 B.C. I feel that people need to know about us, this little group of people that managed to survive 22 centuries of torment and obstacles in the same place.”

History

Perhaps Jews settled here before 161 B.C.E., when the Maccabees, having liberated Judea, sent two emissaries to the Roman Senate. But Jason ben Eleazar and Eupolemus ben Johanan, who went home with promises of protection, were the first whose names we know, therefore “the spiritual ancestors of Western Jewry,” according to Cecil Roth, the late, preeminent historian of Italian Jewry. As Rome expanded eastward, Jewish merchants and diplomats immigrated here. But Jewish slaves—Rome’s promises weren’t worth the bronze they were etched on—became the backbone of the community. Captives brought here after Pompey conquered Judea and Titus destroyed the Temple were ransomed by free Jews or freed by owners exasperated by their refusal to eat or otherwise do as the Romans did.

By the end of the first century C.E., the community of some 12,000 Jews was significant enough to be satirized by Martial and Juvenal, and had produced its own famous author, Flavius Josephus, who chronicled The Jewish War “in alternate bursts of frankness and sycophancy,” as Roth put it. Their fortunes depended on who was emperor and, after the establishment of the papacy, on who was pope. Throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance, despite recurring oppression, Jewish culture flourished. Synagogues developed the Italian rite, Judean in origin, which influenced Ashkenazic liturgy and is still practiced throughout Italy. After 1492, refugees from Spain, Portugal and Southern Italy established Catalan, Castilian, Aragonese and Sicilian synagogues.

The Counter Reformation brought devastating change. The papal bull Cum Nimis Absurdum, issued by Pope Paul IV on July 12, 1555, forced Jews into seven walled acres that became known as the ghetto. Men had to wear yellow hats; women, yellow scarves. Titles of respect (signor, signora) were forbidden as was dealing in anything but secondhand goods. There could be only one synagogue. (In compliance, all five synagogues moved into one building called Cinque Scole, the Five Schools.)

Within the Ghetto walls, an indigenous language, Giudaico-Romanesco, developed; out of the humblest foods came now-celebrated recipes. But the poverty and degradation grew more intolerable every year, lasting until 1870, when the unification of Italy ended papal rule. The rotted tenements were razed and replaced with Belle Epoque palazzi. By 1904, Tempio Maggiore’s dome counterpointed St. Peter’s on the Roman skyline. The recovery from centuries of confinement began with efforts to organize educational, social, cultural and religious institutions. Jews opened businesses and entered professions, becoming so valuable a part of the middle class it seemed they would forever be secure.

But again they became outcasts with the racial laws of 1938, and then fugitives when the Nazis reached Rome. The Gestapo extorted over 100 pounds of gold from Jewish leaders desperate to safeguard the community; nevertheless, 2,091 Jews had been deported by June 4, 1944, when Rome was liberated.

Then another period of healing began. In 1965, Pope John XXIII issued Nostra Aetate, acknowledging all that Jews and Catholics share historically and theologically. As if embodying the spirit of that document, on April 13, 1986, Pope John Paul II crossed the Tiber to visit Tempio Maggiore; in December 1993, the Vatican opened diplomatic relations with Israel.

Rome’s Jewish community warmly greeted Pope Benedict XVI when he visited the synagogue on January 17, 2010, despite controversy surrounding the proposed canonization of wartime pope Pius XII, whose silence during the deportations will only be understood when Vatican archives from the Holocaust period are opened to scholars.

Community

Around 15,000 Jews live in Rome. The most recent wave of immigration brought thousands of Libyans fleeing pogroms incited by the Six-Day War in 1967; they settled mostly near Piazza Bologna. Jews live in Monteverde and around Viale Marconi, too, but there is no Jewish neighborhood per se. Some 1,300 students attend the community’s nursery, elementary, middle and high schools, which are all in one building in the Ghetto. Although the Ghetto remains the spiritual, cultural, culinary and commercial heart of Jewish Rome, only a few hundred Jewish residents remain.

Among the best-known Jews today are the architect Luca Zevi, designer of the Museo Ebraico and the in-progress Shoah Museum; historian Anna Foa; journalist Maurizio Molinari; and the Nobel prize laureate Rita Levi-Montalcini. Most Jews are in business; many own shops; some vend souvenirs around town (including at the Vatican) as Jews always have. And if you hear one of the Colosseum’s costumed gladiators humming “Hatikva,” don’t be surprised.

Although traditional Judaism is the norm here, as elsewhere in Italy, levels of observance vary. Of the city’s 16 synagogues, Tempio Maggiore is the most visible and visited; Oratorio di Castro and Tempio Ashkenazita (both at via Balbo 33) and Tempio dei Giovani on the Isola Tiberino are also convenient. The newest is Shirat Ha-Yam in Ostia. For information about services, kosher grocers and accommodations, contact the community office (011-39-06-684-0061;www.romaebraica.it).

Sights

First, visit the Museo Ebraico di Roma at Lungotevere Cenci 15 (39-06-6840-0661;www.museoebraico.roma.it) to get a sense of the city’s Jewish past and present. Museum collections include many ketubot and other objects donated by local families. Among textile masterpieces from the Cinque Scole is a 16th-century Ark cover with spiral columns representing the lost Temple in Jerusalem that might have influenced Gianlorenzo Bernini’s columns symbolizing Rome as the new Jerusalem in his Baldacchino at St. Peter’s. A sumptuous sky-blue brocade Torah cover was made from a discarded dress of Bernini’s friend, Queen Cristina of Sweden.

Included in museum admission is a tour of Tempio Maggiore, where the flowery stained-glass windows and fabric-like painted walls of the mehitza suggest the central role textiles played in the ghetto economy. The interior of the synagogue is as majestic as its aluminum-domed façade, but less sober. The joyous, Missoni-like rainbow motif inside the cupola alludes to the contract between God and man.

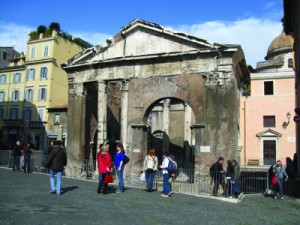

Nowhere is the sweep of local Jewish history more palpable than in the piazza in front of the Portico d’Ottavia (all that’s left of the library Augustus built for his sister, Octavia), which is in its third millennium of bearing silent witness to Jewish life in Rome. This piazza is now called Largo 16 Ottobre 1943. To your right looms Teatro di Marcello, the ancient amphitheater where Jews hid during the occupation; it now houses condominiums of the rich and famous. Behind the portico is Sant’ Angelo in Pescheria, one of the churches where ghettoized Jews were forced to listen to conversionist sermons; the oratorio is now a wedding showroom for Jewish-owned Limentani (www.limentani.com), a wonderland of kitchen equipment and tableware across the street.

One of the only streets evoking the Ghetto’s haunted past is Via della Reginella, which winds its dark and narrow way up from Via del Portico d’Ottavia to Piazza Mattei, where you will find the Fontana delle Tartarughe (Tortoise Fountain), a Giacomo della Porta marvel (but the tortoises were added later by Bernini).

The number of iconic works of art in this city that have special meaning for Jewish visitors is staggering, starting with the Arch of Titus on the Colosseum end of the Forum. Other must-sees: Michelangelo’s Moses (and the flanking sculptures of Leah and Rachel) in San Pietro in Vincoli and, in the church of Santi Quattro Coronati, the fresco of Pope Sylvester resuscitating a dead bull and Rabbi Zambri failing to do so, a classic illustration of the eternal tensions between church and synagogue.

When in the Vatican be sure to detour (just before the Sistine Chapel) into the Collezione Arte Religiosa Moderna, where you will find works by Jewish artists including Leonard Baskin, Max Weber, Abraham Ratner, Ben Shahn, Jacob Epstein, Aldo Carpi and Marc Chagall.

The Museo Storico della Liberazione (Via Tasso 145; 39-06-700-3866; www.viatasso.eu) occupies the bland residential building that was the Gestapo prison. You still feel the prisoners’ presence in their hope-filled notes, prayers and poems, and in treasures such as the score of “Ninna Nanna” (lullaby), which Don Giuseppe Morosini, a priest, wrote for the pregnant wife of his cellmate, Epimenio Liberi. Morosini, thought to have inspired the character of the priest in Roberto Rossellini’s film Open City, was shot by a firing squad; Liberi died in the Fosse Ardeatine massacre.

The Fosse Ardeatine Memorial (Via Ardeatina 174) is a tranquil park where you walk through a dark tunnel into a mausoleum with row after row of stark tombs, some marked with Stars of David, some with crosses, of the 335 men and boys randomly arrested by the Gestapo and shot in cold blood here on March 24, 1944, in retaliation for 32 German deaths none of them had anything to do with. A gigantic cross and Magen David stand together overlooking the site like a benediction.

Nearby are the underground burial sites of the ancient Romans. Of the five existing Jewish catacombs, only Vigna Randanini on Via Appia Pignatelli is open to tour groups; for visiting information, go online towww.jewishroma.com, www.romeforjews.com or contact Laura Supino at laurasupino@libero.it (individual tours are possible but pricey).

Scholars gleaned most of what we know of ancient Roman Jewry from inscriptions and frescoes unearthed in these eerie, winding tufa corridors where, in the trembling light cast by your guide’s lantern, you, too, will discover their trades (a shohet’s stone is adorned with a cow; “Grammateus” indicates the community scribe); their names and the origins of ours (as in “Asteri,” or Esther); their languages (Greek, Latin, sometimes Latinized Greek); their taste in interior design (the more elaborate chambers were meant to echo their occupants’ homes); and their culinary and other traditions. These latter are expressed in charming, well-preserved drawings of fruits, peacocks, hens, ducks, fish, roses, palms, menoras—and also figures of Fortune and Victory and of cherubs; clearly, the proscription against depicting human figures was not always followed.

We have also learned from the catacombs that there were at least 12 synagogues in ancient Rome. But today, only the ruins of one remain (including its kitchen); it was unearthed in 1961 among the excavations at Ostia Antica, which is closer to Leonardo da Vinci airport than to Rome. Stop here on your way to the city from the airport. After your long flight you will welcome the stroll under umbrella pines, passed the museum, which displays pieces of the synagogue, to the synagogue itself.

Books

Lazio Jewish Itineraries: Places, History and Art by Bice Migliau and Micaela Procaccia (Marsilio) leaves no stone in Rome unturned. Nor does Gardens and Ghettos: The Art of Jewish Life in Italy (University of California Press), edited by Vivian B. Mann for the Jewish Museum exhibition.

Other interesting reads: Elsa Morante’s History: A Novel (Zoland Books); Susan Zuccotti’s Beneath His Very Windows(Yale University Press); The Sistine Secrets: Michelangelo’s Forbidden Messages in the Heart of the Vatican

by Benjamin Blech and Roy Doliner (HarperOne); and Alexander Stille’s Benevolence and Betrayal: Five Italian Jewish Families Under Fascism

(Picador).

Recommendations

The kosher bed-and-breakfast closest to the Ghetto is Migdal Palace (Corso Vittorio Emanuele II 173; 39-06-6889-0091; www.migdalpalace.com). Pantheon View (Via del Seminario 87; 39-06-699-0294; www.pantheonview.it) is also near the Ghetto and mere minutes from the monument Lord Byron managed to depict in only five words: “simple, erect, severe, austere, sublime.”

Micaela Pavoncello (www.jewishroma.com) and Roy Doliner (www.romeforjews.com) both offer terrific tours.

And you will want to cram in as much authentic cucina ebraica as possible, starting in the morning with a simple ciambello (sugared doughnut) from the legendary Boccione Bakery (Via del Portico d’Ottavia 1; 39-06-687-8637), which, consumed on the run, is the traditional local breakfast. Or try the fruitcake-biscotto hybrid known as pizza ebraica. On Fridays, Boccione has halla.

Innovation hasn’t characterized Roman Jewish cuisine for centuries. Now, however, three kosher restaurants have taken the treif out of iconic trattoria fare like spaghetti alla carbonara. It is made with zucchini at Nonna Betta (Via del Portico d’Ottavia 16; 39-06-6880-6263) and with dried beef at Taverna del Ghetto (Via del Portico d’Ottavia 8; 39-06-6880-9771) and Ba’Ghetto (Via del Portico d’Ottavia 57; 39-06-6889-2868), which also features cucina tripolitana, reflecting the owner’s Libyan heritage.

Many restaurants offering typical Roman Jewish cuisine are not kosher, including Franco & Cristina (Via del Portico d’Ottavia 5; 39-06-687-9262), perfect for a quick, affordable lunch of pizza al taglio (by the slice) or Roman Jewish daily specials like aliciotti con l’indivia (fresh anchovies with endive). Go before noon or after 2:30 or you will run into everyone in the neighborhood.

There is no way to avoid crowds at tiny Sora Margherita (Piazza delle Cinque Scole 2; 39-06-687-4216), but the homemade agnolotti, carciofi (alla Giudia or especially alla Romana) and pears caramelized in red wine are worth the hassle. Reservations advised.

Finally, three great gelato stops are only steps from the Ghetto: Alberto Pica (Via della Seggiola 12; 39-06-6813-4481); Antico Caffe dell’Isola (Via Ponte IV Capi 18, on the island between the ghetto and Trastevere); and Bernasconi (Piazza Benedetto Cairoli 16; 39-06-688-0264), where gelato, available only during the summer, and everything else is kosher.

No Roman holiday, ebraico or otherwise, would be complete without truly world-class gelato!

Elin Schoen Brockman is currently working on a novel. Her Web site is www.elinschoenbrockman.com.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Ferdinand says

Supporting Israel isn’t just the perspective of Ayn Rand but also grneudod in common sense. Since Israel is a an extension of Western civilization we have a moral obligation to support countries that reflect open societies like ours.In Israel proper every citizen (regardless of race, religion or creed) enjoys rights and liberties protected by the country’s constitution while the country is surrounded by despotic Islamist regimes. Despite Israel being predmoniately Jewish, it is still mostly secular. When was the last time you heard of a gay pride parade taking place in Gaza, Mecca, or Tehran? They take place regularly in Israel and prostitution is legal there too.A proper government is one that is geared to protect individual rights in which Israel’s government does just that (albeit not consistently). As far as Zionism is concerned, I know little about it except most who reel against it do so because of its call for a Jewish state.With your support of the Palestinian “right-of-return” (so called) and talking up their defenders (like Miko Peled) it is not only Israel you condemn but also what the country stands for and you claim to support: Western civilization.