Being Jewish

Commentary

When Resisting Anti-Jewish Hate Is Women’s Work

With an alarming rise in anti-Semitism around the world, now is an opportune moment to reflect on Jewish women past and present who responded to threats to our people. The upcoming holidays of Purim and Passover bring to mind the brave biblical women who rescued the Jews when they were targeted for annihilation. At Purim, we recite the story of Queen Esther, who risked her life to unmask Haman’s evil plot to murder Persia’s Jews. Although the Passover Haggadah doesn’t mention Moses or anyone else in his family, we remember how his mother, Jochebed, defied Pharaoh’s order to hand over her infant son to be drowned. When she could no longer hide him, she set Moses in a basket on the bank of the Nile, where Pharaoh’s daughter was bathing. When Miriam, Moses’ sister, spotted the princess rescuing her brother, she brought her mother over to nurse him. Were it not for the courage of Jochebed and Miriam, there would have been no Moses to lead the Israelites out of Egypt.

But such bravery is not limited to our biblical stories. Millennia later, Jewish women in the United States spoke out against baseless hatred. In her poem “The Exodus (August 3, 1492),” Emma Lazarus recalled her Sephardic ancestors as “dusty pilgrims” expelled from Spain. Their exodus enabled their New York-born descendant to celebrate America’s openness to other victims of oppression. When, in 1881, Russian pogroms sparked a new Jewish exodus, Lazarus’s poem “In Exile” welcomed the refugees to this land that granted Jews “Freedom to love the law that Moses brought.” Lazarus extended that welcome in her iconic sonnet “The New Colossus,” which is affixed inside the Statue of Liberty museum: “Give me your tired, your poor, / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

In the early 20th century, two-term Hadassah National President Rose Halprin joined Hadassah’s voice to other Jewish groups appealing to President Franklin D. Roosevelt to denounce Germany’s persecution of its Jews after Hitler came to power. Halprin, who lived for a time in Jerusalem, traveled from there to Berlin in the 1930s to assist with Youth Aliyah, Hadassah’s project to rescue German Jewish children and bring them to Palestine. Likewise, she witnessed the Arab anti-Jewish riots breaking out in prestate Israel.

Halprin had moved back to the United States when, on April 13, 1948, a convoy of Hadassah medical personnel was ambushed by Arabs on its way to the hospital on Mount Scopus, murdering at least 78 people, including doctors and nurses. With the hospital cut off from the new State of Israel, Halprin, then serving her second term as Hadassah president, undertook the construction of a new hospital in Jerusalem at Ein Kerem.

More recently, other American Jewish women have put themselves on the line. When, for example, historian Deborah Lipstadt denounced Holocaust deniers, one of them—David Irving—sued her for libel in Britain. She titled her account of their 1996 court battle History on Trial. (Spoiler alert: She won.) Today, Lipstadt continues to expose hatred and bigotry in her new book, Antisemitism Here and Now.

When I reflect on today’s anti-Semitism, I look back to its first instance on American soil. In 1654, when 23 Jews landed in New Amsterdam, the colony’s governor, Peter Stuyvesant, tried to expel this “deceitful race.” But as an American Jewish historian who writes and teaches on the topic, I take solace—and hope others do, too—in the scholar’s long view of anti-Semitism waxing and waning across American history.

I also know that standing up against anti-Semitism isn’t always as straightforward as it seems. In November 2017, for instance, I testified before the House of Representatives Judiciary Committee about the proposed Anti-Semitism Awareness Act. The bill seeks to define anti-Semitism to help the Department of Education investigate violations of Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. (Title VI prohibits discrimination based on race, color or national origin in programs receiving federal funding.)

Venerable Jewish groups like the Anti-Defamation League and Hadassah support the bill. While I admire its intent—to guarantee an official response when anti-Semitism surfaces on college campuses—I find the bill problematic. Its language potentially violates our freedom of speech, particularly as it relates to criticism of Israel. Moreover, I am reluctant to legislate a definition of a term that can change over time. The word anti-Semitism wasn’t even coined until 1879. Incisive observers today talk about a new anti-Semitism recycling old beliefs about a Jewish race while newly centering enmity of Israel at its core.

Venerable Jewish groups like the Anti-Defamation League and Hadassah support the bill. While I admire its intent—to guarantee an official response when anti-Semitism surfaces on college campuses—I find the bill problematic. Its language potentially violates our freedom of speech, particularly as it relates to criticism of Israel. Moreover, I am reluctant to legislate a definition of a term that can change over time. The word anti-Semitism wasn’t even coined until 1879. Incisive observers today talk about a new anti-Semitism recycling old beliefs about a Jewish race while newly centering enmity of Israel at its core.

In confronting the complexities of contemporary anti-Semitism, I have climbed onto the shoulders of Jochebed, Miriam and Esther as well as Emma Lazarus, Rose Halprin and Deborah Lipstadt. In resisting anti-Semitism, they passed on to us a powerful legacy of standing up to bigotry and evil.

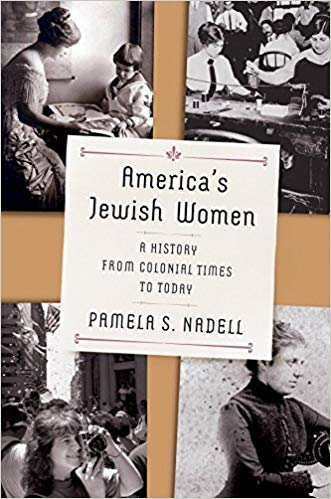

Pamela S. Nadell is a historian and director of the Jewish Studies Program at American University in Washington, D.C. Her new book is America’s Jewish Women: A History from Colonial Times to Today (W.W. Norton).

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Hank Kasven says

I am pleased to have reserved my copy of this book. I look forward to be reading about this very interesting topic.Having lived in two communities, one northern NY and one in northern Me. I can relate to many forms of anti-semitism that people don’t even realize they are participating in.