American View

Feature

The Jewish Response to Modern-Day Slavery

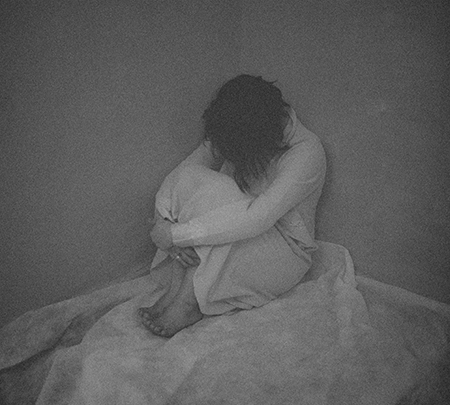

Sandra is anxious as she talks on the phone from her home in California. The retired psychotherapist is a rarity,

one of the few Jewish survivors of human trafficking willing to share her experience. “It’s so very difficult for me,” she admits. “I can’t even sit still. I’m walking around. I’m ironing. I’m making breakfast for the dog. The depth of pain permeates my psyche, and time doesn’t lessen the impact.”

Sandra (not her real name) is also featured in a short YouTube video created by the Jewish Coalition to End Human Trafficking in San Francisco, part of a citywide collaborative. Shadowed in darkness to preserve her privacy, she describes being molested at age 6 by three close relatives, one of whom forced her to have sex with his friends for money.

The exploitation continued for six years until Sandra told a trusted teacher in her public school.

“She said, ‘I’m going to put a stop to this,’ ” Sandra recalls. “ ‘I’m coming home with you.’ ” The teacher confronted Sandra’s mother about what was happening under her roof, and the abuse stopped.

Today, Sandra, 82, is married and has adult children and grandchildren. “There’s still that part of me that is that young girl,” she says. “I’d rather move on, but you don’t. You move around it. You develop coping mechanisms, like eating. Some people use drugs, alcohol. Therapy is helpful.”

Years ago, she hired a private detective to find the teacher who confronted her mother over a decade before educators became required by law to report abuse. “I told her of the tremendous gains I had made in my life and thanked her for her courage.” Sandra says that if the teacher, a Jewish woman, hadn’t shown up at that school that year, she “would have probably gone out on the street, an alcoholic by the time I was 15 or 18 and would have carried my lack of self-worth right into the world of prostitution. People would have said, ‘She came from such a nice family, how could she have done something like this?’ ”

Sandra’s story is different from most current narratives of sex trafficking. Those tend to center around young kidnapping victims from developing countries forced into the sex industry, or on lurid, high-profile cases, such as that of financier Jeffrey Epstein, who committed suicide in a Manhattan jail in August 2019 after being charged with the sex trafficking of girls as young as 14.

The exploitation Sandra experienced as a young child highlights the dangers to vulnerable individuals in the Jewish community. Some Jewish organizations as well as a number of Jewish women working in the larger nonprofit world have prioritized the fight against sex trafficking, part of a broader fight against human trafficking, which also includes trafficking for labor. They have created support structures for sex trafficking victims, pushed for legislation on both the state and national levels and designed educational programs to prevent and publicize the scope of the problem.

“Human trafficking is a key human rights issue because it exploits some of the most vulnerable people on the planet. It’s also a key Jewish issue because so much of our national identity is about moving from slavery to freedom,” says Rabbi Lev Meirowitz Nelson, director of education for T’ruah: the Rabbinic Call for Human Rights. “Every human being must be treated with the dignity befitting an image of God.” T’ruah and the National Council of Jewish Women co-lead the Jewish Coalition Against Trafficking, a group that includes Hadassah.

The United States State Department reports that nearly 25 million people worldwide—an estimated 800,000 in the United States alone—are victims of human trafficking. Worldwide, the industry, also called modern slavery, makes over $150 billion a year, about $99 billion of that from forced sex work. (Estimates from other organizations, including the Global Slavery Index and the United Nations’ International Labour Organization, put the number of those being trafficked as high as 40.3 million. The magnitude of the problem is hotly debated, because no sound methods of data collection exist. Overlaps between sex and labor trafficking and forced marriage and difficulty in distinguishing between prostitution and forced commercial sex work also muddy the waters.)

According to a 2019 Trafficking in Persons Report from the State Department, the United States ranks as one of the top three countries of origin for victims of human trafficking, along with Mexico and the Philippines. The Trafficking Victims Protection Act, enacted in 2000, which made human trafficking a federal crime, defined it as the “recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person” through “force, fraud, or coercion” for any sort of work; and any commercial sex “induced by force, fraud, or coercion” as well any commercial sex in which the individual involved is a minor.

The number of sex trafficking victims and perpetrators—Jewish or otherwise—is unclear. Due to stigma and lack of research, “we simply don’t know the scope of the crisis in the Jewish and larger community,” says Lauren Hersh, a former Brooklyn prosecutor who in 2009 created one of the first sex trafficking units in the United States under the late Brooklyn District Attorney Charles Hynes. She is also co-founder and national director of World Without Exploitation, a national coalition of 160 organizations, many headed by survivors, that works together on anti-trafficking policy, legislation and education. “Victims are often too terrified and traumatized to talk about it, and often are silenced by perpetrators and society.”

“Trafficking exists in the shadows,” says Jody Rabhan, chief policy officer for the National Council of Jewish Women, which has made fighting sex trafficking a priority since its founding 125 years ago. “We often don’t see it and don’t even recognize it.”

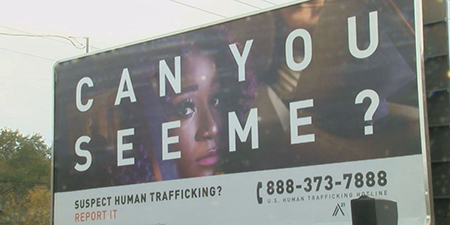

The National Human Trafficking Hotline website, run by Polaris Project, features a map with reports from around the country—not just in urban areas but in rural and suburban areas as well, wherever the demand for sex and cheap labor exists.

“We can extrapolate how widespread it is—on the web, on street corners, in massage parlors and bars,” says Rabhan. From Jewish survivors, she says, it is clear that sex trafficking happens to both boys and girls.

For her part, Sandra knows what it feels like to come up against insensitive responses to her story. “Through the years I’ve heard, ‘It happened a long time ago.’ ‘Get over it.’ ‘Why didn’t you say no?’ ”

Sandra lived with her parents until she was 23 but during that time did not confront her abusers, in order to keep peace in her family. “Men were held in higher esteem in my family than women, and nobody wanted to look at the shame,” she explains.

It was only in her 50s, when she was in therapy, that she finally wrote letters to the perpetrators about what she had experienced at their hands. Her father stopped talking to her and the abusers either denied what had happened or ignored her letter altogether.

Sandra says she feels compelled to share her story “to bring knowledge to the Jewish community that abuse and trafficking exist within our homes and communities.” Indeed, over the course of her career in psychotherapy, Sandra says, she has met many survivors of trafficking—some of whom have been Jewish.

One of the few programs nationwide dedicated to helping Jewish women who are victims of or are at risk for trafficking is The Mishkan Project, established in 2016 by Sanctuary for Families, a leading New York service provider for domestic violence and trafficking survivors. Mishkan (“sanctuary” in Hebrew) advocates for victims who have been arrested, represents them when they apply for immigrant status (a few of the young women are Israeli-born) and offers counseling services, high school equivalency and college preparatory support as well as an intensive job-readiness program. Today, the project is supported by UJA-Federation of New York, the Brooklyn Community Foundation and the Jewish Women’s Foundation of New York. Mishkan has helped 50 Jewish women to date, most of them Orthodox individuals from the New York metro area.

The profiles of these Jewish women are similar to other trafficking victims, notes Lori Cohen, former director of the Anti-Trafficking Initiative at Sanctuary. Girls in the United States usually enter into prostitution between the ages of 12 and 14, according to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. Risk factors include early sexual abuse, learning difficulties and rejection by family or community that leads to homelessness or foster care.

Traffickers have become savvy at recruiting through social media like Instagram and Snapchat, says Cohen, now the executive director of ECPAT-USA, the United States branch of ECPAT-International, formerly known as End Child Prostitution and Trafficking. She outlines a typical scenario: “The trafficker creates a false persona and befriends a 13-year-old girl who has low self-esteem, as some adolescents do. He becomes a virtual boyfriend who says, ‘You’re so pretty. Can you send me more photos? Do you want to meet me somewhere? Your parents don’t understand; your friends don’t understand.’ He promises her all sorts of things. She thinks she is in love with him, meets him and finds herself being pimped out shortly after.”

ECPAT-USA works with schools to teach educators and students about the risks and causes of child trafficking. It’s critical to talk about “the commercialization of sex,” says Cohen. “The purchase of sex is what fuels trafficking.”

Hadassah’s policy statement on combating human trafficking notes that it not only harms the victims involved, it “also undermines the social, political and economic fabric of the nations” where human trafficking occurs by “devaluing individuals, demeaning women, and increasing violence and crime.” Hadassah units have partnered with community advocacy organizations, and programs about trafficking often highlight the work of the Hadassah Medical Organization’s Bat Ami Center for Victims of Sexual Abuse in Jerusalem, a treatment center for Israeli survivors of sexual abuse, including those who have been trafficked. In the United States, Hadassah advocated for reauthorizing the Trafficking Victims Protection Act and the Stop, Observe, Ask and Respond to Health and Wellness Act, which provides health care workers with training on the issue. Both were signed into law in 2018.

trafficking advocates.

In January, to mark the 20th anniversary of the initial passage of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, the State Department declared 2020 the year of Freedom First, focusing attention on the problem of human trafficking. The White House hosted an anti-trafficking summit for advocacy groups and legislators at which President Trump signed an executive order creating a new post on the Domestic Policy Council solely focused on combating human trafficking. The order also expands education programs and housing opportunities for survivors of trafficking and prioritizes the removal of child pornography from the internet. “My administration is putting unprecedented pressure on traffickers at home and abroad,” the president said at the summit. “We enacted bills to fight sex trafficking, increase support for survivors and raise the standards by which we judge whether other countries are meeting their duty to fight human trafficking.”

The summit was organized by Ivanka Trump, the president’s daughter and adviser and a vocal advocate for anti-trafficking legislation.

That the administration is focusing national attention on human trafficking “is a good thing,” says New York Assemblywoman Amy Paulin (D-Scarsdale), who has worked on anti-trafficking legislation at the state level.

At the same time, she noted that a few national anti-trafficking organizations did not attend the summit, in part because of opposition to the administration’s stance on immigration.

“Some of the policies on immigration the administration has adopted have prevented trafficking victims from entering our country and fleeing their abusers,” says Paulin, who was not invited to the summit. The administration has “also attempted to deport trafficking victims instead of giving them a home in the U.S. Perhaps the Freedom First initiative will be eye-opening to those same policymakers and will help them do a better job in helping human trafficking victims.”

Read how the Jewish state became one of the top global reformers in the war against sex trafficking in Turning Around the Record on Sex Trafficking in Israel.

On the state level, California passed a bill in 2017 requiring establishments such as hotels and motels, rest areas, train stations and truck stops to post signs with the National Human Trafficking Hotline.

A similar bill was passed in 2017 in New York State that mandates the placement of hotline information cards in hotel rooms. Paulin is introducing two bills that would mandate training for hotel employees and drivers of commercial vehicles on how to identify cases of trafficking and to alert authorities.

Indeed, a Northeastern University report recently published by the National Institute of Justice found that of all anti-trafficking strategies, the most important to increasing arrests is requiring the national hotline number be posted in public places. Notices have become common across the country, from hotel rooms in Chicago to billboards at rest stops along the New Jersey Turnpike.

Stacey Dorenfeld, the advocacy chair for Hadassah Southern California who lobbied on behalf of the California bill’s initiation and passage, credits Hadassah’s advocacy for educating her about human trafficking. “I have to try to save lives,” says the co-president of the B’Yachad Chapter of Southern California. Dorenfeld herself came across a young woman at a hotel in Florida whom she believes was being trafficked.

She describes how she discovered the woman in January 2019, passed out in an SUV in the parking lot outside the West Palm Beach Marriott. Dorenfeld was there for a Hadassah National Assembly meeting and had gone out early in the morning to meet a friend for breakfast. She noticed a shoe on the ground beside a parked SUV. The oddity of that single shoe made her look inside the vehicle, where she saw a bruised and unconscious young woman.

Dorenfeld opened the car door, which was unlocked. “It was 100 degrees in there,” she recalls. “There were condoms, drugs and drug paraphernalia everywhere.” After calling for help, Dorenfeld tried to revive her. “I began to gently tap her cheek, then a bit harder until she began to come to. I forced her to wake up and was able to get a bit of water in her. I spent over an hour trying to get her up and get water into her, waiting for help to arrive. At each interval of her coming to, I was able to get another number or two from her and finally I had all the digits to her home phone.”

Dorenfeld then called the woman’s parents and told them she believed their daughter was being trafficked. After about an hour, the police and an ambulance arrived and transported the woman to a local hospital. Eventually, she was placed on a train to her parents in North Carolina.

“The issue has captured my heart,” Dorenfeld says, noting the importance of combating trafficking. The young woman in the parking lot “would have died in the car if I hadn’t helped her.”

Rahel Musleah, a frequent contributor to Hadassah Magazine, runs Jewish tours to India and speaks about its communities (explorejewishindia.com).

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply