Books

Israel Through a Range of Prisms

In Israel, a city stroll or a mountain trek connects you to the past. Roads, towns and cities are named for figures from Jewish history. A glance at the ground can reveal pottery shards or other artifacts, even on paths trodden by thousands. Israel may be the only country where archaeology is a regular journalistic beat.

Israel is also where proponents of conflicting narratives cite historical facts to justify their positions on who has the right to be the dominant culture, what are the original names of towns and cities and who is appropriating whose heritage. This abundance of historical information figures into many of the controversies roiling Israel today.

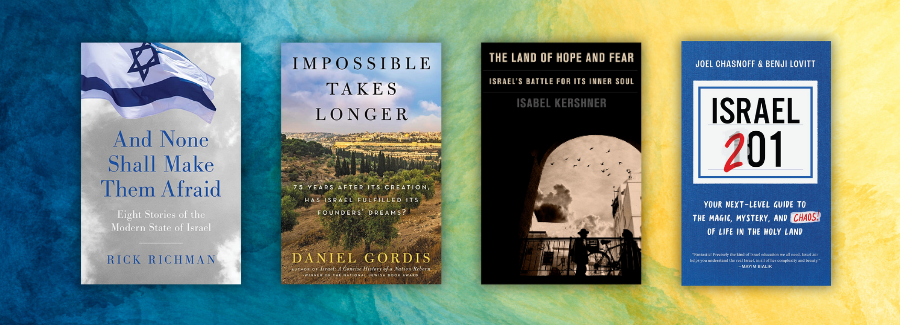

Yet some historical tales still beg to be told, while others require reassessment and shibboleths need to be challenged. These are some of the goals of four books recently published to mark Israel’s 75th anniversary. Through a range of prisms—biographical, comedic, journalistic and persuasive—they seize the opportunity to step back from the onslaught of news out of Israel to develop a clear picture of the country, analyzing how well it is living up to its aspirations and addressing its challenges.

Even as they note some of Israel’s flaws, missed opportunities and mistakes, each book illuminates the successes of the Zionist enterprise. Anti-Zionist detractors make few appearances. Military engagements and terror threats from Iran, Hezbollah and Hamas are conspicuous in their across-the-board absence, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict takes a back seat. Nevertheless, for those who wish to commemorate Israel, they provide an honest and mostly celebratory view of the country.

Missed our webinar? Watch the recording here.

Missed our webinar? Watch the recording here.

Israel and Zionism receive their highest praise from Rick Richman, a resident scholar at American Jewish University in Los Angeles with a slew of books and essays about Israel and Jews on his resume. And None Shall Make Them Afraid: Eight Stories of the Modern State of Israel (Encounter Books)—the title a quote from the prophet Micah—profiles Zionist and Israeli thinkers, activists and politicians in rough chronological order: Theodor Herzl, Louis Brandeis, Chaim Weizmann, Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky, Golda Meir, Ben Hecht, Abba Eban and Ron Dermer. All eight, except for Dermer (Israel’s former ambassador to the United States and newly appointed minister of strategic affairs), have been the subject of numerous biographies both complimentary and critical.

Richman writes that he selected these individuals to “illustrate the central ideological saga of the twentieth century—the struggle between free societies and their totalitarian enemies—and the relevance of that struggle to the emerging story of the twenty-first.” He wants to bring “seminal Jewish and American stories back into common knowledge, so they can do some work in the world.”

Richman exhumes Herzl’s earliest writings to illustrate that the infamous Dreyfus trial was not the starting point of his Zionism. In his coverage of his other subjects’ public careers and speeches, Richman similarly attempts to dismantle widely accepted opinions and stereotypes. He may make you rethink some of these familiar figures. For example, he made me more generous in my opinions of Meir and Eban, who are largely criticized or dismissed in Israel.

Citing their speeches and writings, Richman showed me that both were tougher than I had thought. Their statements and actions would put them nearer to today’s nationalist camp in Israel than to the Labor Party—their actual political home. In 1974, Meir convened a conference of Socialist international heads of state and party leaders, and directly confronted her long-time associates about their lack of support for Israel during the Yom Kippur War. Their absence reinforced something she had learned in the pre-World War II Evian Conference: “Jews neither can nor should ever depend on anyone else for permission to stay alive,” she wrote in her autobiography. Eban was snubbed first by his Labor Party colleagues and then by Yitzhak Rabin, the incoming prime minister in the wake of Meir’s resignation after the Yom Kippur War, despite his career of soaring speeches and diplomacy. In 1948, Eban said at the United Nations: “The sovereignty regained by an ancient people, after its long march through the dark night of exile” will not be “surrendered at pistol point…. If the Arab States want peace with Israel, they can have it. If they want war, they can have that, too. But whether they want peace or war, they can have it only with the State of Israel.”

American Israeli comedians Joel Chasnoff and Benji Lovitt provide timely slices of Israeli life in Israel 201: Your Next-Level Guide to the Magic, Mystery, and Chaos! of Life in the Holy Land (Gefen Publishing House). Divided into eight themed chapters, their assemblage of articles and interviews can be read in any order depending on which subjects appeal to you (the Israeli psyche, the Hebrew language, government, the Israel Defense Forces, etc.) Well researched and laugh-out-loud funny at times, their reports of conversations with Israelis provided me with smiles of recognition:

“Joel called the customer service department of his new Wi-Fi provider. Here’s an actual snippet from that conversation:

JOEL: I’m having trouble connecting the Wi-Fi to my smart TV.

REP: Why would you buy a smart TV if you’re not smart enough to

use it?”

They praise Israeli directness by comparing how Americans and Israelis would respond after a business meeting presentation: “Americans would make indirect and passive aggressive comments such as, ‘Let me think about it.’ ‘There’s a lot of really great stuff in here.’ ‘It was (dramatic pause to choose words carefully)…interesting.’ To each of these responses, here’s what an Israeli would have said: ‘I don’t like it.’ ”

Chasnoff and Lovitt don’t shy away from describing what they see as Israel’s failings, such as the ultra-Orthodox state rabbinate’s restrictive view of Jews and Judaism. But they also wisely steer clear of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, instead focusing on what comedians do best: observing and commenting wryly on the wonders and quirks of Israeli life.

Jerusalem-based New York Times correspondent Isabel Kershner, in contrast, mines both Israel’s past and present to delve into some of the country’s current challenges in The Land of Hope and Fear: Israel’s Battle for Its Inner Soul (Alfred A. Knopf). Divided into 11 chapters, she covers topics such as the Ashkenazi-Sephardi-Mizrahi divide, the complexities of Arab Israeli life and contemporary Israeli culture. Through outstanding writing, she introduces us to a diverse cast of characters, many of whom she had interviewed previously for the Times, and the settings in which she meets them. Her portrait of Negev desert dweller Assaf Shaham, for example, describes the drive to Ein Yahav, where he lives, in ways that help readers better understand the man. “It was still another hour’s drive along Route 90 to Ein Yahav through the moonscape-like Great Rift Valley abutting the Jordanian border,” she writes. “The wind-sculpted cliffs tapered out into a monotonous plain broken only by flat-topped, thorny acacia bushes, providing dappled patches of shade. In this harsh, inhospitable terrain, the Zionist enterprise had been boiled down to its essence.”

The book provides tantalizing historical nuggets, such as letters David Ben-Gurion wrote to national poet Haim Gouri and Menachem Begin, the second of which shows Ben-Gurion’s growing appreciation for the future prime minister.

Kershner notes an important truth when she writes that old grudges run deep in Israel and past slights get “retold like the Passover Haggadah.” Her narrative makes clear that the splits in Israeli society and politics aren’t new, but go back to its earliest days, even to pre-state debates between Jabotinsky’s Revisionists (and later Begin’s Herut) and Ben-Gurion’s Mapai Socialists.

The most ambitious of these four new works is Daniel Gordis’s Impossible Takes Longer: 75 Years After Its Creation, Has Israel Fulfilled Its Founders’ Dreams? (Ecco), the title a reference to a slogan used by the United States Army Corps of Engineers during World War II. Following on the heels of his 2017 National Jewish Book Award-winning Israel: A Concise History of a Nation Reborn, Gordis, Koret Distinguished Fellow at Shalem College in Jerusalem, seeks to understand the degree to which Israel has met the aspirations of its Declaration of Independence.

First, he marshals data, primary sources and anecdotes to examine the Declaration’s goals, such as equality and human rights for all. A keen student of Israeli history, Gordis tells a fascinating story of how the document evolved beyond early drafts that echoed the American Declaration of Independence to reflect the competing agendas of Israel’s founders.

Gordis then assesses how well Israel’s actions over the next 75 years matched those early goals. He counts as successes Israel’s achievements in providing a home where Jews can live freely as Jews; in turning Jews into active participants in the making of their own history; and the flourishing of Israeli culture, particularly the restoration of the Hebrew language. As for Israel’s shortcomings, Gordis is critical of the West Bank settlement enterprise, Israel’s treatment of its Arab citizens as well as the West Bank’s Palestinian residents and the state rabbinate.

One interesting idea Gordis sets forth is that Israel is an “ethnic democracy,” rather than a Western-style, liberal democracy. The former concept has been popularized among political scientists with the pioneering work of Israeli sociologist Sammy Smooha, (whom Gordis does not credit). Smooha says such a democracy is built around the ethos and values of its dominant “tribe”—an ethnic or religious group—while remaining committed to defending minority rights.

Gordis does not sufficiently tease out how the tribalism inherent in an ethnic democracy differs from the individualism of a liberal democracy, as practiced in the United States. Comparing these models could have provided a framework for understanding the growing divide between Israeli and American Jewry as well as among Israelis. It could also be helpful as a guide for identifying ways of reconfiguring Israeli politics to address the strife of the past few months, when hundreds of thousands of Israelis joined rallies to protest the current ultranationalist government, which has advanced legislation to curb the Supreme Court’s independence, among other pushes.

But none of these books makes predictions or offers solutions. Though Kershner claims that Israel “seems to have lost its internal compass,” the portraits she draws don’t offer a path to regaining it. Gordis, like the rabbi he is, asks more questions than he answers. The comedians’ look at Israel gives a street-savvy view of the country, and Richman brings us inspiring words, but both veer away from connecting them with current challenges.

One might wish that these authors had been willing to dig deeper into Israel’s psyche, but these are largely celebratory, after all, and on the 75th anniversary of its founding, Israel deserves them.

Alan D. Abbey is a research fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute with a 40-year career as a journalist, teacher and media professional in both the United States and Israel. Born in Brooklyn, he moved to Jerusalem in 1999.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply