Israeli Scene

Feature

The Female Heroes on the Battlefield and Homefront

On the morning of October 7, Eden Nimri awoke to a cacophony of air raid sirens and mortar fire. The 22-year-old Israel Defense Forces captain grabbed her rifle and dashed off in her pajamas, along with four fellow female soldiers, to the nearby migunit, a freestanding bomb shelter on the Nahal Oz army base in the South of Israel where they were staying that Shabbat.

The last photo Nimri took that day—and the last ever—was from inside the bomb shelter, a place that usually provides safety from rockets and mortar fire. On that day, however, it would become a death trap. The photo shows the four other soldiers in position, one of them kneeling with her gun cocked and aimed toward the entrance of the shelter.

What happened after that is a story of tragedy, bravery and one small miracle.

On that day, women in Israel from all walks of life found themselves cast into situations they could never have imagined—both on and off the battlefield. Against the dark events of October 7, many shone as heroes, among them, Eden Nimri.

It was only by chance that Nimri and her squad were at Nahal Oz, an army outpost located a mere quarter mile from the Gaza Strip and adjacent to Kibbutz Nahal Oz. As an officer in the Artillery Corps’ Rochev Shamayim, or Skyriders unit, Nimri’s job was to provide reconnaissance for elite commandos by setting up small drones to observe and photograph the enemy. She was constantly on the go throughout Israel but was told to stay somewhere in the South that weekend. There happened to be room for her and her squad of four at the Nahal Oz base.

Also in the bomb shelter were around 30 other female soldiers who had been stationed near Gaza in their duties as spotters, known as tatzpitaniyot in Hebrew, a word with a feminine conjugation since all spotters in the IDF are women. As they huddled in the shelter, the mortar fire continued almost unabated. Then, a message came in on Nimri’s communication device: “Infiltration! Infiltration! Infiltration!”

Nimri gestured to her soldiers to load and cock their guns and aim them at the rear entrance of the bomb shelter. She did the same, positioning herself facing the front entrance. The spotters, unarmed, crouched against a wall in terrified silence. That’s when Nimri snapped the photo and sent it via WhatsApp to others in her company to let them know the situation.

Minutes later, a bearded Hamas terrorist wearing a green bandana burst into the shelter—through Nimri’s side—brandishing a Kalashnikov. She and her soldiers fired at him, killing him instantly.

Then, three hand grenades were thrown into the shelter. There were explosions, smoke, chaos. Nimri’s soldiers, along with six of the spotters, dashed out through the back of the shelter while Nimri single-handedly battled the terrorists who stormed through the front. With her firing, the 10 women were able to escape and ran into two nearby rooms on the base, locking the doors. They hid there for hours as terrorists sang, danced and shouted in rapture right outside their rooms. The terrorists tried to pry open the locked doors several times. They could easily have entered through a broken window if they had noticed it.

After six and a half hours in hiding, the 10 soldiers were rescued by paratroopers who had arrived at the base.

Nimri, who had never been in a combat situation before, died fighting. Nearly all the other women on the base, including those who remained in the bomb shelter with her, were either killed or kidnapped. All except for the 10 who snuck out while Nimri alone fired at the terrorists. Many other soldiers who had been stationed at the base were also killed in the attack, as were 14 civilians at nearby Kibbutz Nahal Oz; numerous others were wounded or kidnapped, some of them since released in hostage-prisoner exchanges.

That Saturday morning, Sharon and Michael Nimri, Eden’s parents, had planned to drive from their home in Modi’in to Nahal Oz to share a picnic lunch with their daughter. “We woke up at 8:30,” recalled Michael Nimri. “We didn’t know it at the time, but by then Eden was no longer with us.”

The details of what happened at the base were relayed to Nimri’s mother and father by the soldiers of her squad. Her parents weren’t surprised by her conduct.

“She was always a fighter,” said her father, pointing to Eden’s years as a competitive swimmer and her determination to make it into the air force’s pilot training course, which she did—one of just 24 women in the group of 300 trainees. As an accomplished swimmer, she could have opted for the army’s Outstanding Athlete Track, which includes lighter service requirements, but instead chose combat service, he noted.

“She was never one to cut corners just to try to save herself; she took her responsibility for others seriously,” said Sharon Nimri, who also recalled another, softer side of her daughter. “She would come home in her dirty, smelly uniform after two weeks in the field, go up to shower and emerge transformed, looking like a princess. And then she would kind of melt—she loved getting hugs and massages at home, cuddling with me on the sofa.”

Nimri was one of at least 37 female combatants killed that day out of the thousands who fought. In no Israeli war have so many women excelled on the battlefield in such an array of positions as on that Black Saturday, as October 7 has become known in Israel, and its aftermath. Among them was an all-female tank crew—apparently the first anywhere in the Western world to engage in combat—whose members killed some 50 terrorists, saving at least one kibbutz in the process. The actions of soldiers like Nimri and the female tank crew have put to rest the long-simmering debate in Israel about the suitability of women serving in combat.

It was not only female soldiers who proved to be brave, determined and resourceful on that grim day. So, too, did civilians—women like Naomi Galeano, a 30-year-old volunteer medic with United Hatzalah. That morning, Galeano, who works as a coordinator of a Sherut Leumi (National Service) program, was preparing her two small boys for Simchat Torah celebrations at their synagogue in Ramat Beit Shemesh, west of Jerusalem. When air raid sirens went off, Galeano, who is observant, turned on her special radio device and heard the plea from the head of the local branch of the United Hatzalah emergency service.

“There is something terrible going on in the South,” she recounted him saying. “We need help. Anyone who is sober, please contact me urgently.” Many had been drinking as part of the Simchat Torah festivities the previous evening, Galeano explained.

After the third call for volunteers and a brief talk with her husband, Galeano packed her medic’s bag and headed off with her neighbor, Avi Bar-Lev, a United Hatzalah ambulance driver. Just blocks from her Ramat Beit Shemesh home, they encountered a rocket stuck into the side of the road, a remnant of that morning’s barrage from Gaza some 30 miles away.

Just before noon, they reached the Heletz Junction, which intersects Road 232, the north-south highway that runs parallel to the Gaza Strip. It would be hours before the IDF would arrive in the area. Other United Hatzalah members advised them to keep a weapon in arm’s reach at all times. Bar-Lev drove with one hand on his gun, the other on the steering wheel, while Galeano held the spare magazine with bullets as they made their way further south. “Through the thick smoke and fires, all we could see were overturned cars and bodies,” she recalled. The pair had received some reports that something extremely out of the ordinary was unfolding in the South but had no idea about the extent of the carnage.

When they finally saw the lights of a border police car, Galeano breathed a sigh of relief—until they noticed that the car was upside down, with seven or eight dead soldiers surrounding it. Maneuvering so as not to run over bodies—they had been instructed by a United Hatzalah area supervisor not to stop anywhere along the way—they eventually arrived at their first destination: an airfield where they treated and loaded injured soldiers onto helicopters, working nonstop through air raid sirens and booms.

Next, they were summoned to Kibbutz Sa’ad, a border community about halfway between Sderot and Kibbutz Be’eri. Upon arriving, guns were pointed at them by members of the kibbutz security squad and someone with a megaphone yelled at them to get out with their hands up and identify as Jews. “With my hands up, and shaking like crazy, I started screaming ‘Shema Yisrael,’ ” Galeano recalled. “They apologized and explained that some terrorists had tried to take police cars and ambulances, so they had to take precautions.”

Bar-Lev and Galeano entered the gates of the kibbutz to find that a gun battle was in progress. “The kibbutz security team yelled at us to lay down on the ground,” she said. “Bullets were whizzing by and there were cries of ‘Allahu Akbar,’ and I was just praying I’d stay alive.”

At any point, Galeano could have turned back and gone home. The United Hatzalah field coordinators repeatedly gave all volunteers that option—but Galeano said she and Bar-Lev never considered it.

“I had seen so many dead people by then,” she recalled of that day, “I felt I had to see for myself that there were still living people among us, people I could help.”

She also felt that she was continuing a family tradition. “My grandfather was a medic in the paratroopers,” she said. “My grandmother was a commander in Nahal,” one of Israel’s main infantry brigades. “I come from a family that fought to be here.”

Galeano and Bar-Lev dashed, often under fire, between kibbutzim, the helicopter base and a makeshift treatment center set up at the Heletz Junction for the next few days. They treated injured soldiers, kibbutz members and concert-goers from the Nova music festival, which had been a prime target of Hamas. One man had a hand that was badly bruised, almost deformed. “He told us he had been holding the handle of the door of the safe room for 11 hours while the terrorists tried to pry it open it,” Galeano recounted.

Later, friends in her religious community would ask her repeatedly how, as a mother, she could have “abandoned her children” that day—a characterization that makes her bristle. “I tell them that they were perfectly safe with my husband, and the reason I went was because that was my way to keep them even safer.”

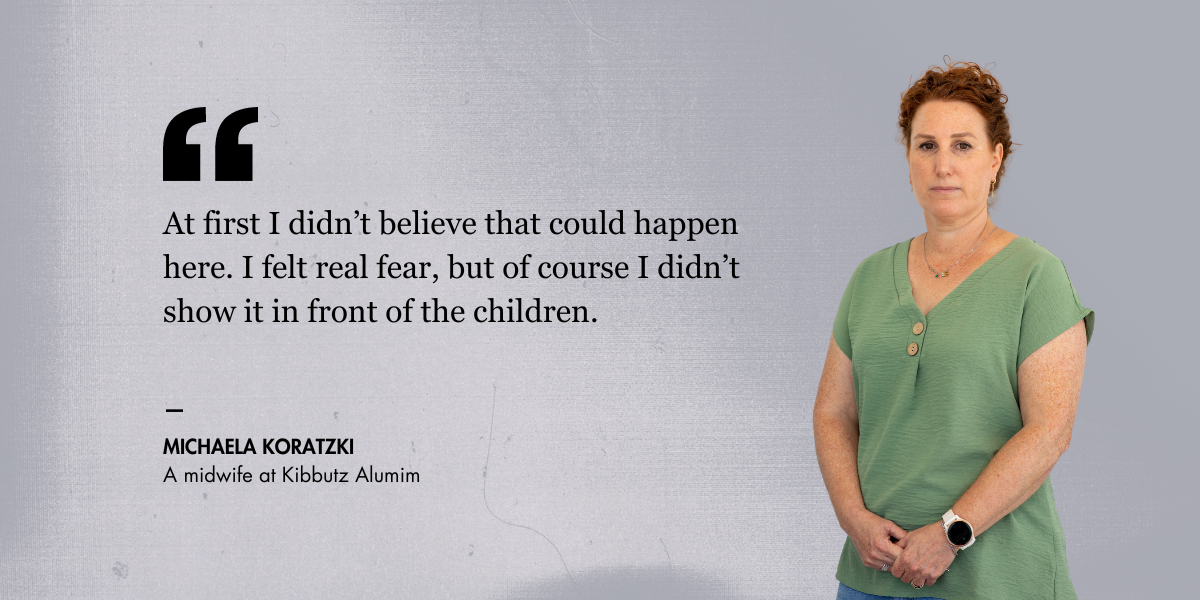

On October 7, the boundaries of the battlefield and homefront in Israel disappeared, bringing war into the kitchens and living rooms of ordinary women like Michaela Koratzki, a midwife at Kibbutz Alumim, another community along the border with Gaza that is home to about 100 families.

Koratzki, who works in Soroka Medical Center’s obstetrics department in Beersheba and as a community nurse at her kibbutz, was in the saferoom of her home that Saturday morning after the first air raid siren sounded. Accompanying the 45-year-old were her husband, four children and in-laws.

Not long after they entered the room, her husband, Zvi, a member of the kibbutz security team, received a radio report from a colleague alerting him that terrorists had infiltrated the grounds. “At first I didn’t believe that could happen here,” she said. “I felt real fear, but of course I didn’t show it in front of the children.”

A battle between the kibbutz’s 12-man security squad and some 20 heavily armed Hamas terrorists was raging right outside their home, near the entrance of the kibbutz. The terrorists had already massacred many of the foreign farm workers housed on the outskirts of the community.

Koratzki, used to handling complications of birth, was now focused on fending off death once the squad began bringing the wounded straight into her kitchen.

She recalls that it took her a few minutes to make the switch from domestic mindset to battle mindset. “When they brought the first injured man, a neighbor of mine, into my home, my first thought was, ‘Oh no, blood is dripping on my clean floor,’ ”she said with an embarrassed smile. That passed as she began treating her neighbor, Amichai Shacham, who had “a hole in his upper arm” and shrapnel in his hand. She tended to him under her kitchen table to keep them both out of range of bullets whizzing past the window. She had only basic first aid equipment at home, but she improvised.

Minutes later, Shacham’s next-door neighbor, Ayal Young, also a member of Alumim’s security squad, was brought in gasping after sustaining three bullet wounds in his upper back. With the help of other kibbutz members, Koratzki was able to get hold of more dressings—she had run out—and oxygen. But she knew that Young, who was spitting blood, would not survive if he didn’t get to a hospital soon.

With a gun battle still underway, no ambulances could enter the kibbutz. Koratzki’s husband used his own car to evacuate Young while terrorists fired RPGs intermittently at vehicles exiting Alumim.

“Ayal arrived at Soroka hospital unconscious and in shock,” Koratzki said. “They stabilized him and took him right into the operating room. If he had arrived just a few minutes later, I was told that he would not have made it.”

Koratzki felt that Young’s wife, Reut, had to be informed about his condition in person. So, when the fighting moved from right outside her house to another corner of the kibbutz, she hurried over to the couple’s home accompanied by an armed neighbor, Eran Schlissel, whom she had just treated for bullet wounds. “I was scared,” she remembered. “I knew there were terrorists on the kibbutz, but I felt it was my duty.”

There were at least three incursions of terrorists on Alumim that day. The security squad fought off the first on their own. Much later, IDF forces arrived and helped retake control of the kibbutz. There were no fatalities among kibbutz members that day, and all the injured security squad members treated by Koratzki are recovering or already back on their feet.

When her family was evacuated the following day, they saw how close they had come to a different fate. Terrorists’ bodies were strewn on the kibbutz lawns and paths, including, ironically, at Hadar Garden, named after soldier Hadar Goldin, who was killed during Operation Protective Edge in 2014 and whose body has since been held in Gaza by Hamas.

It will probably take years to tell the stories of the female heroes of October 7 and the ensuing war. A few are etched in the consciousness of Israelis and many around the world. They include Rachel Edri, who kept the terrorists holding her and her husband hostage in their Ofakim home distracted for 17 hours by plying them with cookies and tea—until a special force was able to kill their captors and rescue the couple.

And Inbal Rabin-Lieberman, the security coordinator of Kibbutz Nir Am who, with quick thinking and good organization, got the security squad armed and ready before the terrorists arrived at the gates, making it one of the few kibbutzim in the South whose residents suffered no deaths or major injuries.

Both women have been honored in multiple ways, including with gigantic murals of their images on walls in Tel Aviv.

Most of the women who answered the call of duty that dark day will never be known. And even those who are—a soldier from Modi’in, a medic from Ramat Beit Shemesh, a midwife from Alumim, to name just a few—will not get a medal or a mural for their courage. But many in Israel owe them their lives.

Leora Eren Frucht is a Canadian-born feature writer and editor living in Israel.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Christine McAdam says

Leora’s tribute to the female heroes in Israel has reinforced for me the truths for the brave female heroes that I may have been taking for granted. I honor their sacrifice to serve and protect and save others lives and will not allow them to be forgotten in my conversations with others here in Canada.

Hope kate says

This will never end. I believe in prayer. However as much as I believe in God I also believe that two side with the same equal willingness to die for a value means they are willing to take the world out before they decide to stop and share equally and peacefully….they will kill one and other til the last man or woman stands and take everything and one with them….so u fortunate….if the land was so important then why would they destroy it and all that was in it …this is about leadership….this is about power. This isn’t about a holy peace of land or u would respect it as something of the Lord’s! Thou shall not kill …. remember? ECT ECT ECT…….

Hope kate says

This will never end. I believe in prayer. However as much as I believe in God I also believe that two side with the same equal willingness to die for a value means they are willing to take the world out before they decide to stop and share equally and peacefully….they will kill one and other til the last man or woman stands and take everything and one with them….so unfortunate….if the land was so important then why would they destroy it and all that was in it …this is about leadership….this is about power. This isn’t about a holy peace of land or u would respect it as something of the Lord’s! Thou shall not kill …. remember? ECT ECT ECT…….