Books

Feature

New Books Examine Our Post-10/7 Landscape

On August 6, 1945, the Enola Gay, an American B-29 bomber, dropped a nearly 10,000-pound atomic bomb on Hiroshima, leveling the Japanese city, killing some 146,000 people and ushering in the nuclear age. A year later, the American public had only a vague sense of the human misery caused by the war-ending mushroom clouds at Hiroshima and, the next day, over Nagasaki. The public had only seen images that had passed through United States military censors.

Enter Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist John Hersey. In spare prose devoid of commentary, he described the lives of six individuals before, during and after the “terrible flash.” The resulting New Yorker article and landmark book, Hiroshima, both published in 1946, completely changed the American conversation about the use of atomic weapons.

Beyond unfathomable destruction and loss of life, there are few similarities between the American bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—many still debate the justness of the bombings—and the sadistic, unprovoked murders and kidnappings launched on October 7, 2023, by Hamas and allied terror groups. And the first batch of books to reflect on October 7 have arrived in a vastly different world from 1946. Today, we have an abundance of sounds and images: The perpetrators filmed and broadcasted their barbarous acts. The film Screams Before Silence, documenting Hamas’s unspeakable acts of sexual violence as acts of war, can be seen on YouTube.

We can’t expect even the most powerful book to impact the conversation on the Israel-Hamas war to the degree that Hersey’s did—or to engender any sympathy for Israel among those who oppose its very existence. So, what kind of impact can books possibly have on our wrecked landscape?

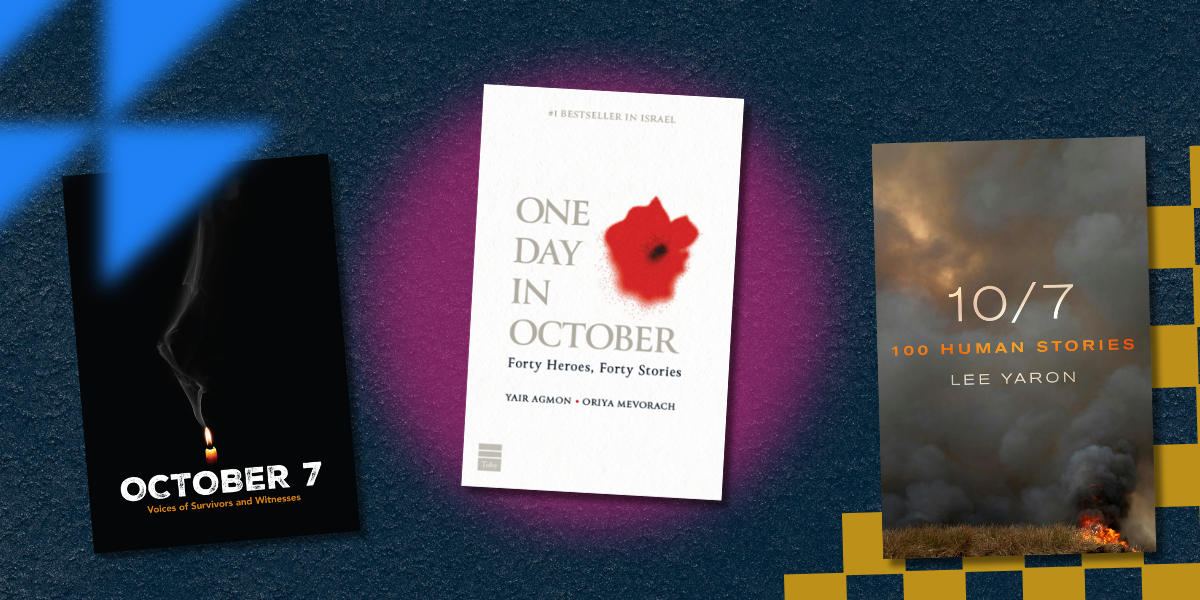

Quite a lot, it turns out. A trio of new volumes—10/7 by Lee Yaron, One Day in October by Yair Agmon and Oriya Mevorach and October 7 compiled by Tal Chaika—manage, like Hiroshima, to rescue individual stories from the anonymity of statistics. They also do something else. Very much like Donna Rosenthal’s underrated 2003 gem, The Israelis: Ordinary People in an Extraordinary Land, these three books paint a portrait of Israelis in all their diversity: ravers, idealistic kibbutzniks, Netanyahu supporters, Religious Zionists, Bedouins, Druze, foreign workers, police and soldiers, parents and kids.

Yaron’s 10/7: 100 Human Stories (St. Martin’s Press) draws most directly from the bottom-up reporting techniques employed by Hersey. It also is the only one originally published in English. In the afterword, Yaron’s husband, Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Joshua Cohen, likens the work to the Yizkor books that memorialized whole towns eradicated in the Shoah. Yaron, a correspondent for Ha’aretz, describes herself in the book as “the daughter and granddaughter of refugees and survivors of the Holocaust. I am a Jew; I am an Israeli; I am also a woman, a feminist, a journalist, and a proud adherent of the camp that supports the rights of all peoples between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea.”

Through scores of interviews, Yaron immerses the reader in the utter confusion of the assault and the terror of not knowing. Different chapters offer snapshots of how this awful day was experienced in towns such as Sderot and Ofakim, in kibbutzim like Be’eri and Kfar Aza and at the Nova music festival.

At its best, the book powerfully relays human stories, often ones that haven’t received wide attention. Like the account of Amar Abu Sabila, a Bedouin who died in Sderot saving two young girls who had seen their mother gunned down only to have his own body remain unidentified for weeks because he was mistakenly buried with terrorists.

Until now, I hadn’t heard much about how at least 1,000 Ukrainians, refugees from the 2022 Russian invasion of their home country, were forced to flee the southern city of Ashkelon on October 7. One of the most memorable tales in 10/7 involves Eitan, one of those refugees, a Jewish boy raised in an Odessa orphanage and now living in Ashkelon. We learn of his harrowing flight, first to Moldova with members of his extended family and ultimately to Israel and his heartbreaking reaction once the rockets started on that Shabbat morning.

“Eitan was sure he was going to die, he just didn’t know whether by a missile strike or a terrorist’s bullet,” Yaron writes. By chance, he lived.

This important work has a few flaws. Yaron attempts to link so many stories that the reader has to strain to keep the names straight. Further, the two sections that provide historical and political context, while thoughtful and balanced, carry a rushed quality and take the reader away from the human accounts that are the book’s essence.

By highlighting victims and survivors, One Day in October: Forty Heroes, Forty Stories (Toby Press) accomplishes many of the same things as 10/7, though it approaches the telling from another perspective. Both Agmon and Mevorach wish to celebrate heroism, those who “emerged from the shelter of their homes, charged into the inferno and fought like lions to save lives.” They seek to change the October 7 narrative from victimization to heroism.

I found myself uncomfortable with the attempt to draw redemption from the carnage. Or with defining heroism or separating heroes from the rest of those directly affected by the attacks. How can anyone judge the behavior of someone frightened for their life?

Still, the power of these 40 monologues made me reconsider. Perhaps miraculous things did happen. Again and again, we read accounts of men, women and those not much older than children sacrificing themselves to save family members, of police and soldiers choosing again and again to go into harm’s way to try and save others.

One example is the story of Amit Mann, a paramedic from Kibbutz Be’eri, told by her sister, Miri. On that day, amid the booming of missiles and the sirens, a friend invited her to leave for Netivot. She “insisted on staying in the kibbutz to treat the wounded,” which she did for hours with little equipment and little help until she herself was killed by terrorists. “From her perspective, if she could save just one or two or three people, then she did what she had to do in this world. That was Amit.”

October 7: Voices of Survivors and Witnesses (Prospecta Press) was compiled by Tal Chaika, an Israeli product manager at a high-tech firm, with an introduction by Israeli President Isaac Herzog. The book represents an effort by the Israeli public itself to capture the feelings and emotions of traumatized people in the days, weeks and months after October 7.

“The turmoil, both personal and national,” Herzog writes, “will continue to haunt us for years to come.”

On that level, the book succeeds. I have not traveled to Israel since October 7, yet I suspect this book gives some semblance of what it must feel like to be there, to encounter such raw trauma.

Nevertheless, the gathered blog posts, poems, journal entries and eulogies lack the immediacy of the other works. Though not without moments of inspiration and heartbreak, the reader feels weeks removed from the events and sometimes is not provided basic information or context.

After reading these three heartbreaking books, I was reminded of the remarkable nature of all Israelis and Israel itself. Whether or not the government can project any sense of vision or competence, after reading hundreds of pages about the worst moments in the country’s history, I was left with the feeling that the people who managed to create such full lives and vibrant communities will endure this and whatever is to come. These works made me think that, just maybe, Israelis can rekindle the hope for peace. That thought flickered for just a moment.

Bryan Schwartzman, a writer living outside Philadelphia, hosts the podcast Evolve: Groundbreaking Jewish Conversations.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Bud Polatsch says

Terrifying and wonderful. I read about 10/7 and lived through the atomic bombing and the subsequent nightmare. Your narative was sensational and gripping! Thanks for sending it!

Bruce Fox says

Powerful book review about that nightmare day. Reading these books must have been so heavy. I am glad they also provided a flicker of hope. In the words of Sarah Blondin, may only love make sense.