Health + Medicine

These Medical Clowns Are Healing Israel

On October 7, 2023, a 23-year-old paratrooper with bullets in his arm and lung dragged a fellow soldier to safety through gunfire—only to discover he had rescued a corpse. The bullet wounds inflicted by terrorists at Kfar Kisufim near the Gaza border healed faster than the soldier’s psyche. While the hole in his lung eventually closed and vascular surgeons at the Hadassah Medical Organization in Jerusalem repaired his torn arm with an artery from his leg, the trauma stayed with him, month after month.

Today, that soldier, whose name is withheld for his privacy, is on his way to being sound in both mind and body. Improbably, men and women with painted faces and red noses were among those who aided him, and he is now training to join their ranks as Israel’s first wounded soldier to become a medical clown.

For over two decades, Israel’s medical clowns have helped hospital patients throughout the country cope primarily with short-term stress, from managing postoperative pain to fear around medical procedures. Now, they have adapted their techniques of improvisation, theatrics, physical comedy and therapeutic care to play a key role in helping thousands navigate the horrors they experienced on and since October 7. This clowning subdiscipline, developed in Israel by clowns working with Israel Defense Forces soldiers since 2016, is known as rehabilitative clowning.

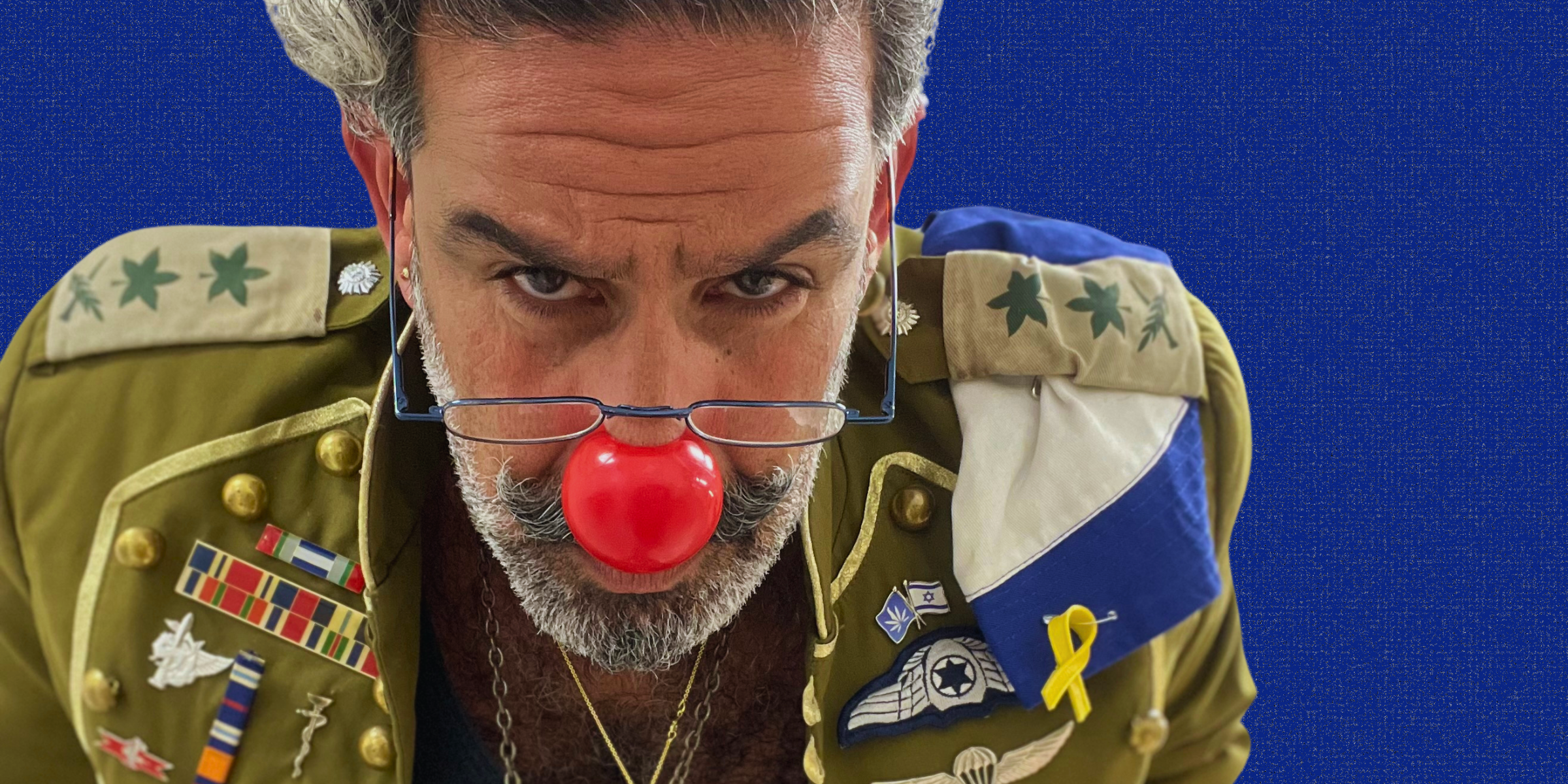

“Because we’re skilled in perceiving how others feel, we can break down barriers and reach those broken by fear, pain and grief,” said David Barashi, 48, head of the Rehabilitation Clown Project at HMO, whose clown name is Dush. “By bringing them close, we can help them through a slow spiral of healing.”

Created as a paramedical field in the 1990s, medical clowning in Israel began at Hadassah Hospital Ein Kerem in 2002, initiated by Barashi with the help of Dream Doctors, a nonprofit that trains and integrates professional medical clowns into Israeli hospitals. Over the past two decades, medical clowns have overcome many raised eyebrows to win recognition as accomplished, multidisciplinary, research-backed health care professionals.

Israel today is “a global leader in the field,” according to Dream Doctors CEO Tsour Shriqui. The country boasts 105 trained medical clowns who contribute to the well-being of an annual 200,000 patients, young and old, in 34 hospitals countrywide.

The clowns’ success in alleviating fear and pain in patients recovering from surgery and undergoing treatment convinced Barashi that their techniques would also be effective in treating psychological trauma—emotional, mental or psychological injury triggered by overwhelming or life-threatening events.

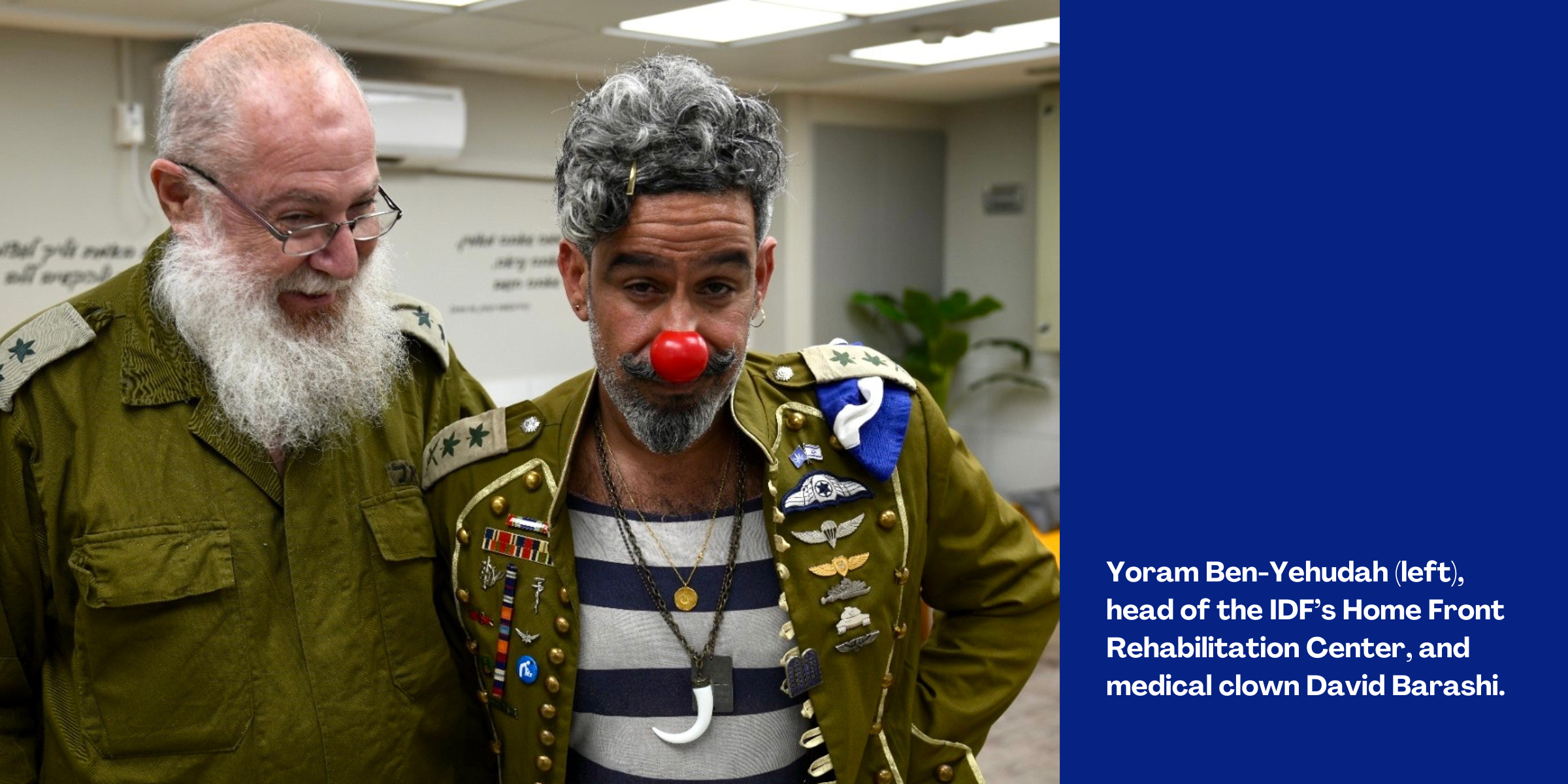

Nine years ago, he brought this idea to clinical psychologist and PTSD expert Yoram Ben-Yehuda, formerly of HMO, who heads the IDF Home Front Rehabilitation Center in Rehovot, one of several centers that treat soldiers for PTSD and other complex reactions to battle. Ben-Yehuda was receptive, and Barashi volunteered weekly to integrate clown therapy into the work of the IDF rehab center’s team of psychiatrists, psychologists and therapists.

Then came October 7. In hospitals nationwide, medical clowns worked around the clock with traumatized soldiers, civilians and their families. Barashi and five medical clown colleagues at HMO covered its two Jerusalem hospitals and visited evacuees and families of hostages.

Ben-Yehuda, meanwhile, was sitting shiva for his son, Itamar, a 21-year-old army medic who was killed battling terrorists on October 7. As soon as Ben-Yehuda returned to the IDF rehab center, he established an emergency trauma unit and recruited Barashi onto its team, while the medical clown continued to work at HMO. “Early intervention can prevent trauma becoming chronic,” Ben-Yehuda said. “It’s a very significant part of rehabilitation.”

Rehabilitative clowning at the IDF rehab center combines therapeutic sessions and resilience training with group acting and improvisation. It is conducted by Barashi and two clown colleagues. One is Amichai Azar—his clown name is Shpachtel—who also works at Hadassah.

“For clowns, there’s no ‘fourth wall’ separating us from these distressed soldiers of all ages and all ranks,” the 50-year-old Azar said. “We can cross barriers and connect, create empathy, allow pain to be shared, give our patients reason to lift their heads. Our approach is designed to help them address and process their trauma in a safe, non-threatening way.”

With many female soldiers impacted by the war, Barashi’s colleague and Dream Doctors female clown Keren Asor-Kliger, 46, (clown name Jonam) was an essential recruit to the team. “It’s a privilege to be part of something so necessary,” she said. “I’ve worked with over 1,000 traumatized soldiers this past year. I’ve been with them at their lowest point, helped bring light back into their lives and accompanied them on their return to life, family and friends.”

Hadassah on Call

Decode today’s developments in health and medicine, from new treatments to tips on staying healthy, with the Hadassah On Call: New Frontiers in Medicine podcast. In each episode, journalist Maayan Hoffman, a third-generation Hadassah member, interviews one of the Hadassah Medical Organization’s top doctors, nurses or medical innovators. Catch up on recent episodes, including a conversation with nurse and sexual health specialist Anna Woloski-Wruble about maintaining sexuality and intimacy as we age. Subscribe and share your comments on the show’s website or wherever you listen to podcasts.

The son of a disabled veteran, Barashi learned early not to look away from those who are injured. In his work with soldiers, Barashi adds Ramat-Clown to his name—a play on ramat kal, the Hebrew for chief of staff—and adapts his own clown costume, adding an army vest and beret over a distinctly nonregulation blue-and-white striped T-shirt, along with his standard red clown nose. He also sports three unbestowed stars of a full general on his shoulder along with a half-dozen fake medals across his chest.

The protocol that Barashi and his colleagues have developed for rehabilitation clowning begins as one-on-one therapy, building nonjudgmental trust and rapport. “We have profound conversations about life, the horror, fallen comrades,” he explained.

It took weeks for a 20-year-old infantrywoman, trapped in images of blood, burning and death from her eight hours in hell at Kibbutz Be’eri on October 7, to open up to a medical clown and other therapists at the IDF rehab center, for example. Slowly, they coaxed her to confront her trauma, and today, she is back with her unit.

This individualized interaction increases as the clown-therapist works on emotional support, social interaction and problem-solving, helping patients confront their fear, grief and anger. The soldiers then move to group sessions in which participants relate their trauma and hear that of others, as resilience and confidence are rebuilt.

“Slowly, they retrieve joy,” Barashi said. “Slowly, they tell stories and they play, visibly repairing themselves.”

The IDF rehab center program includes a weekly visit to the Gandel Rehabilitation Center at Hadassah Hospital Mount Scopus. Its purpose is to give recovering soldiers a sense of helping those like themselves, but it has had another outcome, too. Several soldiers at the IDF rehab center now want to train as medical clowns, and Barashi hopes to inaugurate a program in April to integrate them into the ranks of rehabilitative clowns.

“I want to be a caregiving figure like Dush has been to me,” the wounded paratrooper said. “I want my eyes to tell soldiers in pain, ‘I see you, your difficulty, your fear,’ as his told me.”

Barashi himself is no stranger to trauma. He worked with Covid patients at HMO during the pandemic, and he has volunteered as far afield as Nepal and Haiti following earthquakes.

However, working with soldiers has been a longtime dream. “I’ve always believed I have something to give them,” he said. “No matter their age, background, rank, religious or political outlook, every last one of them is heroic. They’ve defended this precious country with their blood. They’ve been to hell, come back, and many have then returned to the field to fight. It’s my privilege to work with them.”

Wendy Elliman is a British-born science writer who has lived in Israel for more than five decades.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply