Israeli Scene

October 7 Survivors, Then and Now

Two weeks after October 7, 2023, while Israel was still counting its dead, I began writing what would become 10/7:100 Human Stories. This is not a book about tragedy, but about life. As a journalist, I’ve learned that history belongs to the people who live it, not the politicians who spin it. I conducted hundreds of interviews with survivors across generations, and rather than reducing them to victims, I delved into their complete stories—their beliefs, communities and family histories—weaving the deeply personal with the broader political narrative to offer readers a ground-level view. Over the summer, nearly two years later, I returned to see how war changes a society—one family at a time. Here are some of their stories.

‘When I sink into grief, she drifts away’

The Torpiashvili family has about 45 seconds from the start of a siren to get to shelter. The missiles come in that quickly. Their apartment in Ashdod has its own safe room, a privilege many Israelis lack.

Yet to this day, and even during most of the June war with Iran, Avi Torpiashvili often has stayed planted on the couch or hunched over his dinner. “I’d rather take my chances with the rockets than confront the questions that torment me in that room,” he says.

In contrast, Manana, his wife, runs. She pushes Itzik, 13, and Eden, 21, the couple’s two living children, behind the reinforced door, then sits with her ghosts. The guilt always finds her in the safe room—guilt for leaving the television news on for days after October 7, for not taking their 9-year-old daughter, Tamar, to see a psychologist, for letting Avi tell Tamar she was “exaggerating” her fears.

She doesn’t force her husband to join them in the safe room. His refusal has become an expression of his grief.

On October 7, as the Hamas rockets flew into Israel, the Torpiashvili family ran to their safe room 17 times. It doubles as the bedroom of Manana’s mother, who left the former Soviet Republic of Georgia after the Abkhazia war in 1993.

Manana spent the day after the attack crying in front of the television, explaining to Tamar that a war had started. Tamar asked Manana if the children and mothers in Gaza were as afraid as they were.

When the news reported possible terror activity in Ashdod, Tamar went to the kitchen and took out two knives and placed them in the safe room. She told her mother, who was still sitting in front of the television, that she would defend the family if terrorists came.

Through the following days, as the sirens continued, Tamar checked in repeatedly through WhatsApp with her friend Adele, who lives in Ashkelon, as part of her escalating anxiety. While Manana called Tamar’s teacher for advice, her father tried to calm his daughter, telling her she was being “too dramatic” and that she was secure with her family in the safe room.

When a siren sounded at 12:02 p.m. on October 20, following a nearly daily barrage of alerts, Manana called Avi at his work at a supermarket to check that he’d managed to find shelter. She cut off the call when she saw Tamar writhing on the floor. Her daughter soon became unconscious. A neighbor performed CPR before Tamar was rushed to the hospital.

Eight days later, on October 28, Tamar was declared dead from cardiac arrest—a heart attack she had suffered during a warning siren. The State of Israel officially categorized her death as having been caused by “hostile action.”

After her death, Tamar’s room became a shrine. Her bed, covered with a pastel floral quilt, has been buried beneath an outpouring of tributes from around the world. Portraits of Tamar, painted by artists from the United States and Georgia who read about her death and sent their work to the family, lean against the walls. Her school bag sits among red teddy bears given to her in the hospital and drawings that classmates created during the shiva.

Earlier this year, in April, Avi suffered a stroke, paralyzing the right side of his face temporarily. “Your body is expressing your grief instead of your mouth,” Manana says she told him, demanding he see a therapist. His health is improving; he can speak again and has taken a break from work, Manana reports.

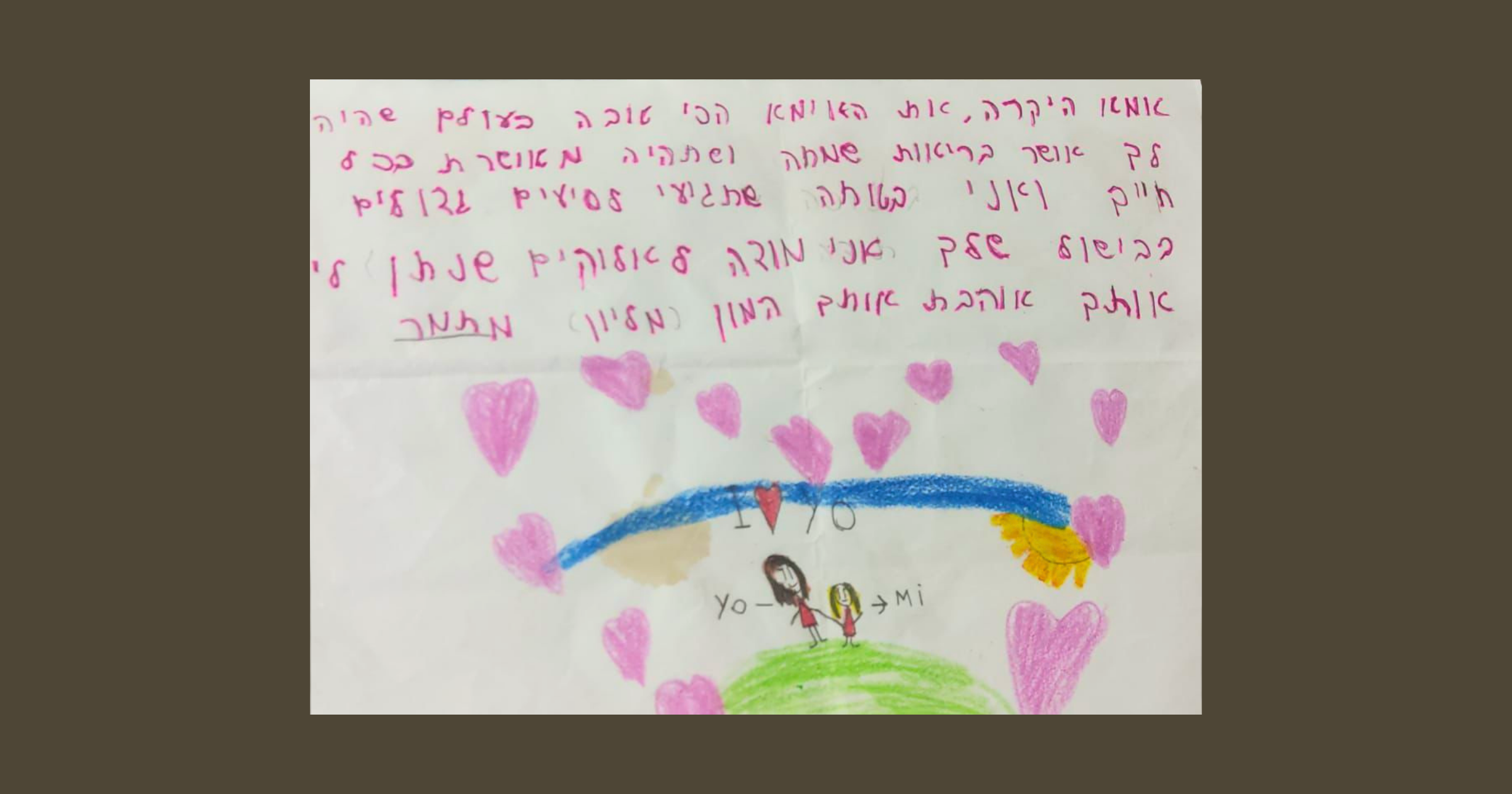

In May, Manana found a card Tamar had written for her at school, a colorful design with big pink letters: “You are the best mom in the world. I want you to be happy all your life and I’m sure you will reach heights you don’t imagine in your cooking.” A few weeks after Manana found the card, she enrolled in pastry school.

“When I feel happy, I feel closer to Tamar,” she says. “When I sink into grief, she drifts away.” Manana has been developing a heart-shaped dessert to name after her daughter.

When Iran unleashed over 500 ballistic missiles at Israeli cities during 12 days of war in June, dozens of buildings crumbled, thousands were evacuated from their homes and civilians were killed in Tel Aviv, Haifa, Beersheva and elsewhere. Some of those missiles struck near Ashdod.

During one of those attacks, Itzik turned to his mother when Avi didn’t move to the safe room. “I don’t want to lose my father, too,” he sobbed into Manana’s arms.

When the next siren wailed, Avi finally entered the safe room with his family and closed the door.

Choosing to ‘live for the living’

A young lemon tree stands sentinel at the entrance of the Epstein family’s new home in Matan in central Israel, its slender branches reaching toward a hand-painted ceramic sign above the doorway that bears the family name in cheerful Hebrew letters. Both the tree and the sign are refugees of sorts.

For two decades, that ceramic nameplate welcomed visitors to the Epstein home in Kibbutz Kfar Aza, where it was mounted beside a towering lemon tree that had grown alongside the family’s children. The house was cramped in those early days, one bathroom for a growing household, so when their firstborn, Netta, couldn’t wait his turn, he’d slip outside to relieve himself against the lemon tree’s trunk.

As Netta matured, he planted basil in the tree’s shade, feeding the herbs with coffee grounds and harvesting leaves for homemade pesto. When the family was evacuated after the October 7 massacre, they could rescue the sign but not uproot the tree. They started over with this tender sapling.

Ayelet Shachar Epstein stands in the doorway beneath the rescued nameplate, her face brightening with a gentle smile as she discusses the future—both her family’s and that of the devastated Gaza envelope communities. “My husband and I made a choice on October 7—to remember what we still have, to live for the living,” she says. “We do our best to keep that promise.”

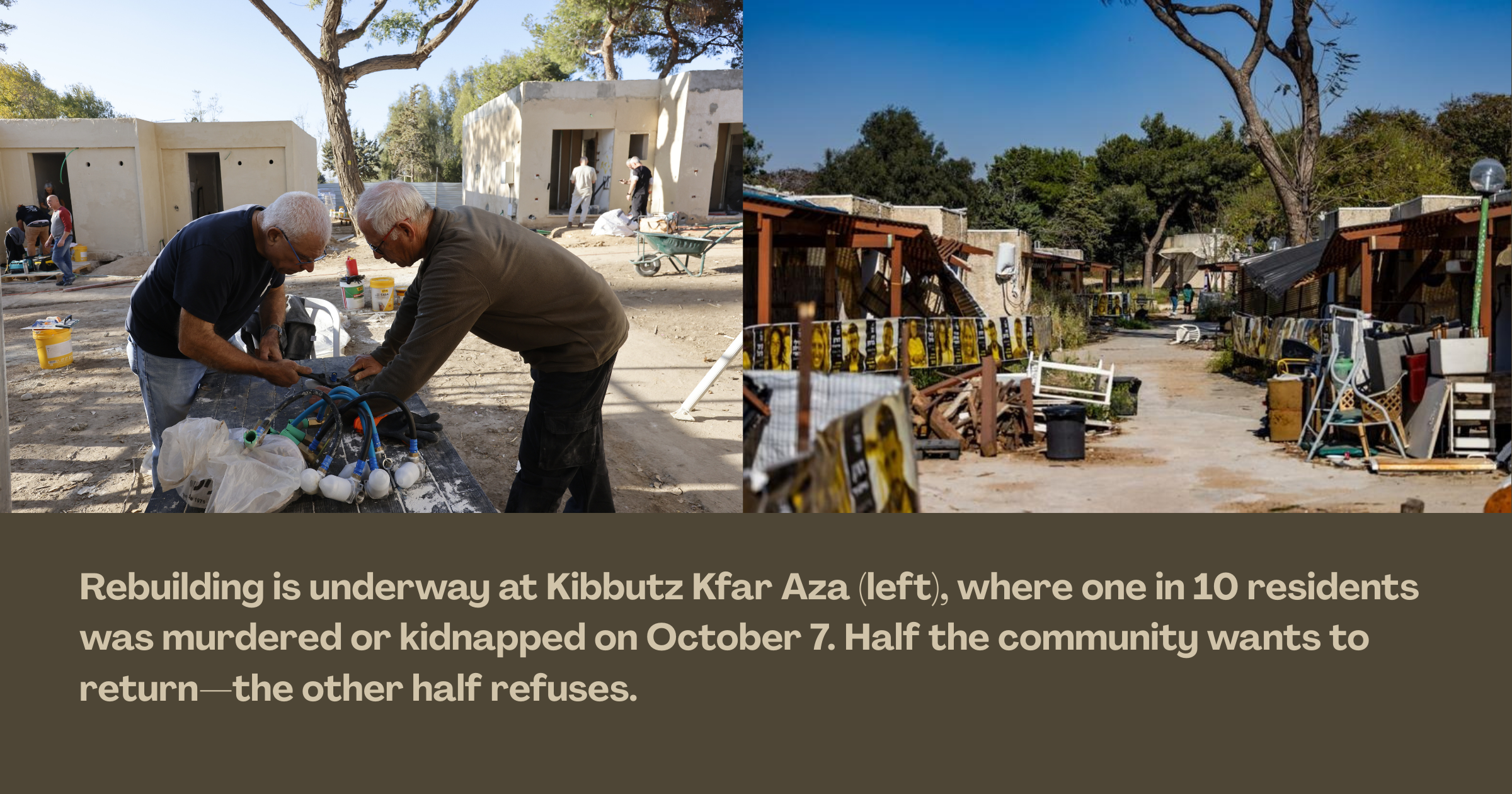

The Hamas assault on Kibbutz Kfar Aza claimed five members of Ayelet’s extended family, including Netta, who was 21 years old. In the kibbutz Ayelet’s parents helped establish, one in every 10 residents was murdered or kidnapped that day. Many of their houses were destroyed and burned.

Ayelet moved to Matan immediately after the attack with her surviving family members, settling near her sister, Dafna Russo, who lost her husband, Uri. Also making the move was her sister-in-law, Vered Liebstein, who lost both her husband, Ofir, the head of Sha’ar HaNegev Regional Council, and their 19-year-old son, Nitzan. “We founded our little village of mourners,” Ayelet says, “adjusting to our new life with five empty chairs at our Shabbat table, supporting each other.”

Hadassah Magazine Presents: Two Years On With Yossi Klein Halevi and Lee Yaron

Join us on Wednesday, October 29 at 12:30 PM ET when Hadassah Magazine Executive Editor Lisa Hostein hosts renowned Israeli writers Yossi Klein Halevi and Lee Yaron for a discussion about what it means to be a Jew today, in a post-October 7 world; how Israeli survivors are coping; and what almost two years of war and rising global antisemitism mean for the future of the Jewish people.

The family had planned to spend that Saturday, October 7, which was also Simchat Torah, gathering at the grandparents’ house and making kites for the Afifoniada—the annual kibbutz kite festival, where residents flew kites over the border with Gaza as a sign that they wished to live in peace.

Instead, at 6:35 a.m., the first rockets shattered the morning calm. Ayelet discovered her mother-in-law, Bilha, one of Kibbutz Kfar Aza’s pioneers, shot dead on her balcony. Within hours, her two brothers-in-law were dead. Uri Russo was found shot dead with six dead terrorists lying around him and six bullets missing from the magazine of his gun.

Ofir Liebstein was no longer an official member of the emergency response squad, but it was clear to him that morning that it was his responsibility to protect his people. He, like many of the region’s residents, was a true believer in the coexistence of Israelis and Palestinians. The months before his murder, he had worked tirelessly to found a new industrial complex designed to create jobs for thousands of Palestinians from Gaza as well as Israelis.

Netta had returned to the kibbutz on October 6 to join the kite festival. Three Hamas terrorists stormed the safe room where he was hiding with his girlfriend, Irene Shavit, and detonated multiple grenades. Netta threw himself on an explosive, sacrificing his life to save hers. “He was the kindest and bravest young man, from childhood to his very last moment,” his mother says.

Today, Ayelet channels her grief into preserving her son’s memory by establishing a training center for young adults who volunteer with children with disabilities, continuing Netta’s own volunteer work with special needs youth.

Like many Gaza envelope survivors, Ayelet voices sharp criticism of the government for failing to prevent the Hamas attack, protect her family and secure the release of the remaining hostages. “We were betrayed, there is no other way to put it,” she states. “If the IDF had arrived on time, Netta and Nitzan could have been saved,” she adds, referring to the Israel Defense Forces. “But the neglect continues, as we still have our people in Gaza.”

Her voice rises as she mentions Gali and Ziv Berman, 27-year-old twins and kibbutz members still held hostage and presumed to be alive. “The government prefers war to bringing them back. What is their plan for our communities’ future?”

The Epstein-Liebstein family refuses to wait for government answers. Less than a year after the massacre, Ayelet’s husband, Ori, ran for the regional council seat left vacant by his murdered brother-in-law. “For our children to play on green lawns again, for young families to return home, we must restore the region,” Ori declared during his campaign. “No one else will do this for us.” He won.

The Kfar Aza community remains fractured. Roughly half the survivors relocated together to Kibbutz Ruhama, about 10 miles from Kfar Aza, hoping to rebuild their kibbutz. The other half refuses to return. “There is real pain and real questions people are asking themselves about the future,” explains Ayelet, whose own family has been splitting their time between the kibbutz and Matan.

The official return date is set for summer 2026, leaving another year of debate about the future of Kfar Aza. Ayelet hopes that by then the war will have ended and Gali and Ziv will have returned home. Meanwhile, she plans to plant new basil in the shade of the young lemon tree.

Her unborn child had acted as a shield

Sujood Abu Karinat was expecting her first child, a baby girl. Her family belongs to a Bedouin clan so large and well-established in the Negev that it has its own village named for them, a formerly unrecognized one that gained official status in 1999, a year before Sujood was born.

Her childhood was spent waiting for the government to set up links to the water and electricity supply. When she was 18, an access road was finally paved and the first permanent buildings were constructed. When she was 19, the district committee approved the development of new neighborhoods with concrete buildings. But for her family, like many others in Abu Karinat, she still lived in a dilapidated tin shack.

At 20, she married 30-year-old Triffy Abu Rashid, a member of the second-largest family in the village, becoming his second wife. Triffy was already a father of six and is himself one of 35 siblings born to his father by three women.

A little after 5:30 a.m. on October 7, Sujood woke up screaming that she was in labor. The couple set off for the hospital. It was early on a Saturday; the roads were empty and the day seemed promising, at least until the sirens started. Despite the warnings, they continued toward Soroka Hospital in Beersheva, usually a 40-minute drive.

As they neared the Re’im intersection, close to the Nova music festival site, two white vans boxed them in. Triffy squinted to confirm what he was seeing: A man armed with a submachine gun was standing on one of the vans. He opened fire.

Triffy swerved sharply to the right, narrowly escaping the ambush. As he glanced over, he saw Sujood bleeding from her abdomen—a bullet had penetrated the car and struck her pregnant belly.

Three passing cars pulled over, as Bedouin residents from the area stopped to help, but another white van soon appeared. Hamas militants began firing indiscriminately at the group, who pleaded in Arabic for mercy. A second bullet struck Sujood in the stomach.

At Soroka Hospital, Dr. Eyal Sheiner, head of the obstetrics and gynecology division, received an urgent message about a new case arriving: “Advanced pregnancy, abdomen penetrated by shrapnel.”

A fetal ultrasound revealed a normal heartbeat, despite the bullet having passed through the uterus and striking the unborn baby in the lower abdomen and leg. Sujood’s internal organs were unharmed; her child had acted as a shield.

Two hours after beginning an operation, Dr. Sheiner reassured Triffy that Sujood was no longer in danger, and he could meet his baby daughter. Triffy gazed at his small, stitched-up daughter, who bore a striking resemblance to his wife. He wasn’t allowed to hold her.

When Sujood woke from surgery in the afternoon, her husband informed her that their baby was alive and in intensive care. But later that night, at 10:24 p.m., their daughter passed away. Sujood never got the chance to see her. The next morning, she asked Triffy to bury their daughter in the village without her presence; she couldn’t bear to see the dead face of her firstborn.

One year later, Sujood and Triffy returned to Soroka Hospital. Sujood gave birth to a healthy daughter they named Malak—angel in Arabic—so she would know she has a sister watching over her. “This baby saved my wife as much as the baby who shielded her did,” Triffy says. “Without Malak, we had life, but full grief. She brought joy and laughter to our lives once again.”

When Iranian missiles struck Israel months later, Sujood and Triffy huddled in their tin shack with Malak, defenseless, as are many Bedouins during wartime. Most nearby Negev villages lack warning sirens or bomb shelters. The Iron Dome, which protects most Israeli cities, does not extend to their communities.

During the war with Iran, Triffy says he called anyone who would listen, begging government offices and the IDF for shelter access: “My wife already lost one child to war. She is traumatized. We need protection immediately.” No help came their way.

Triffy holds onto the hope that before the next war, they’ll find a shelter. “We are Israeli citizens just like anyone else,” he says. “We suffer the same pain and deserve the same protection.”

‘These wars have forced me to grow up’

Eitan Kusenov considers himself blessed. Others might call it optimism. But then again, few 19-year-olds have survived four wars, two direct rocket strikes on their home and won a lottery.

“These wars have forced me to grow up. I’m not the troublemaker I was back in Ukraine before all this began,” Eitan says from his modest home in Migdal HaEmek, a northern city in the Jezreel Valley. “Last week, I welcomed a friend from the orphanage who had recently fled war-torn Ukraine. We’re hosting him, showing him around Israel. I hope his journey will be easier than mine was.”

Eitan was born in Kharkiv, Ukraine, in 2006. His mother, Marina, is Jewish; his father, an alcoholic who abandoned them, Christian. They lived in Odrada, an impoverished and dangerous neighborhood. As hunger gnawed, Marina learned of Tikva (hope), an orphanage in Odessa that offered Jewish children free room and board, education and medical care. Marina had her son circumcised and changed his name: Eduard became Eitan, a Hebrew name meaning “firm” or “stalwart.”

Eitan was 6 when Marina took him on the 12-hour night train to the orphanage. She told him that in Odessa, he’d have a better life than any she could provide. He visited his mother twice a year but they spoke by phone on a daily basis.

By his bar mitzvah, he was fluent in Hebrew, a promising student and an excellent soccer player. Odessa had become his playground. He knew every street and every bar that served alcohol to minors.

He was almost 16 in February 2022, when the Russian airstrikes began. The orphanage’s children were woken by the sound of exploding artillery rounds and shouting in the halls: “Russia’s attacking! Gather your things—we’re leaving.”

By the next morning, the entire orphanage was emptied and 15 buses were on their way to a Romanian seaside summer resort town called Neptun. An empty hotel became a new home for Jewish Odessa. The rest of the Kusenov family—mother Marina, stepfather Anton and older brother Natan—eventually joined Eitan there. They lived together in a small room overlooking the Black Sea.

By 2023, the Kusenovs faced a difficult decision. Returning to Ukraine was unsafe, but in Romania, they lacked permanent status. The solution, it seemed, was Israel. They arrived in February of that year, and their new life in Ashkelon took on a semblance of normalcy. They joined a large community of Ukrainians and Russians who had found refuge in the southern beachfront city. (Some 45,000 Ukrainians have moved to Israel since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war, though many left after October 7.)

On the morning of October 7, they had planned a family trip to the Dead Sea. When the Hamas rocket barrage began, the Kusenovs grabbed their bathing suits and jumped in the car, still hoping to enjoy a swim. As they sped along highway 34, they noticed corpses littering the shoulders and abandoned cars, some with bullet holes in the windows. Eitan was sure he was going to die. At least, he remembers thinking, he would die with his family, not as an orphan.

Eitan returned to Ashkelon to collect the family’s belongings two weeks later, only to discover their apartment building had taken a direct rocket hit. They decided not to return to Ashkelon.

The Kusenovs resettled in Migdal HaEmek, a cluster of dull housing projects as far from Gaza as they could manage. Marina and Anton found factory jobs while Eitan enrolled in engineering classes at the local school, made new friends and fell in love for the first time. “Compared to Odessa, Migdal HaEmek is more like a village than a city, but it’s home,” he says. “I just want to have a regular, boring life.”

But their third home in a little over a year offered no relief. Hezbollah’s rockets followed them, and their seventh-floor apartment meant racing downstairs to the bomb shelter during every air raid.

They learned to live in the pauses between attacks. The family saved enough money to fly to Romania to visit Natan, who had remained with the Odessa Jewish community and had welcomed his first son. They flew back to Israel in June, just in time for another war, their fourth, this time with Iran. Huddled in their bomb shelter, they learned that an Iranian missile had killed a Ukrainian family of five in Bat Yam.

The Kusenovs recently won a government lottery for a subsidized apartment in Migdal HaEmek—their only path to homeownership. After years of constant displacement, the prospect of putting down roots seems almost surreal.

“We’ve lived like moving targets for too long,” says Eitan, who is enrolled in a special engineering program that will delay his army service by about two years. “My only dream is that the wars in both my homes finally end, and never to flee again.”

Their lottery apartment should be ready in three years, assuming no wars delay construction.

Lee Yaron is an award-winning Israeli journalist and author. At 30, she became the youngest-ever winner of the National Jewish Book Award’s Book of the Year for 10/7: 100 Human Stories, which also won the 2025 Natan Notable Books award and landed her on the 2025 Forbes 30 Under 30 list. The paperback version is scheduled to be published in September.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply