Being Jewish

Feature

Angela Buchdahl, ‘An Unlikely Rabbi’

Two lines start forming about an hour before synagogue services, one leading up to the front doors at the top of the steps of the majestic structure, the other leading down to a side door around the corner. The early birds are a mix of ages, talking quietly among themselves amid an air of anticipation. Alice, a friendly older woman next to me in line, says she has been a regular since 1982. She loves the music and the singing and comes early to avoid the rush when many hundreds of others arrive.

What draws the crowd to this corner in midtown Manhattan on a hot Friday evening in July is not a major museum exhibit or Broadway show but a religious experience—a 90-minute weekly Shabbat service that combines music and prayer in a joyful, welcoming way that touches the soul, congregants say.

They are far from alone in their praise. In addition to those who fill much of the 1,400-seat sanctuary, an estimated 50,000 people across the country and around the world livestream the service every Friday evening. On the High Holidays, the numbers approach a million and reach audiences in more than 100 countries.

Welcome to Central Synagogue, a Reform congregation whose roots go back almost two centuries. Over the last two decades, it has undergone a transformation in ritual and engagement, highlighted by innovation and inspired congregational singing. In the process, it has become the largest synagogue in the world, doubling its number of member households to approximately 3,400—with a thousand more on its waiting list. At a time when sociologists note the steep decline in religious affiliation and worship among American Jewry’s liberal denominations, Central, as it’s known, is thriving.

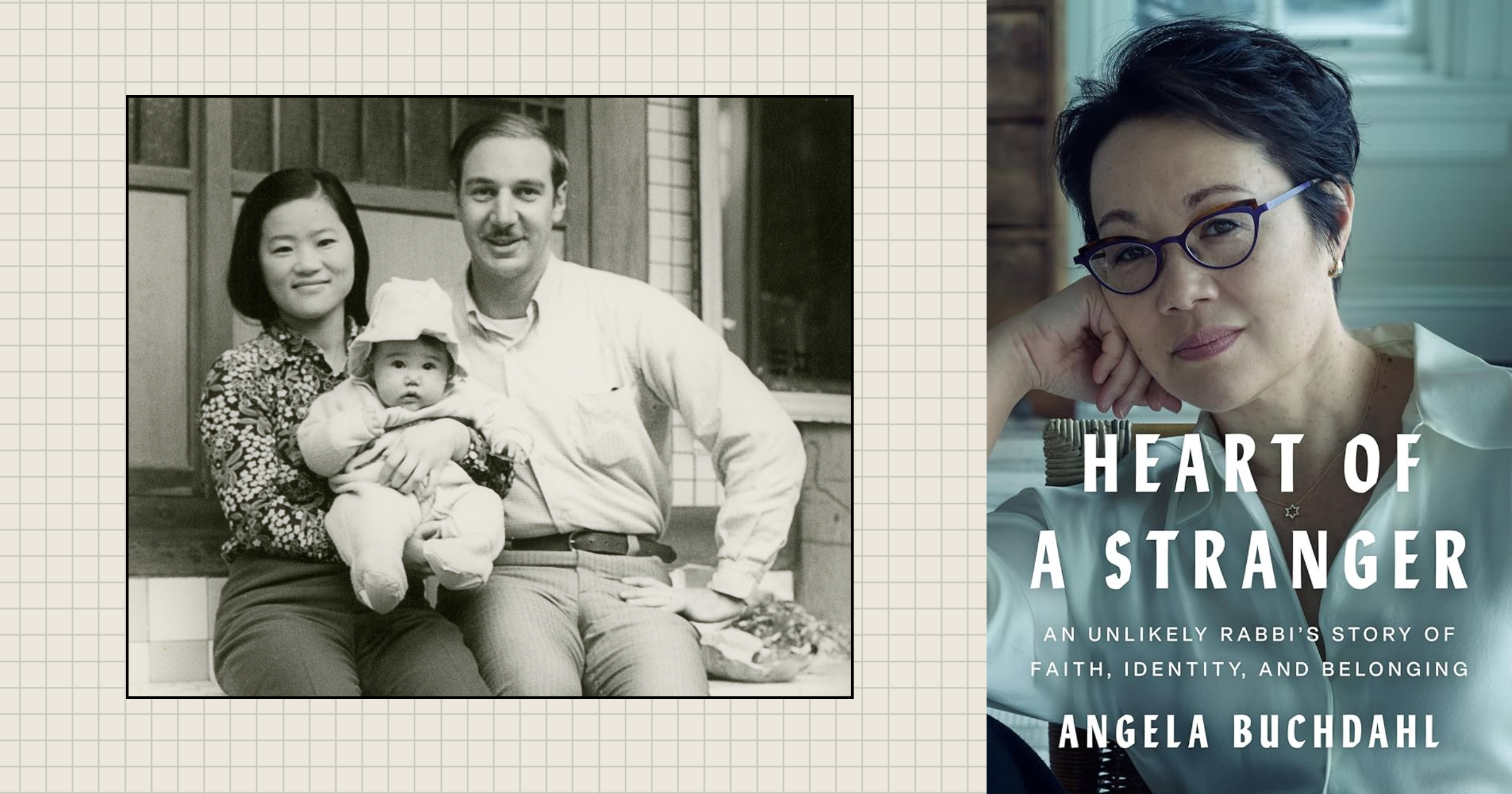

A key reason for the synagogue’s remarkable success is its spiritual leader and former cantor, Rabbi Angela Buchdahl, 53, who describes herself as “an unlikely rabbi,” given that she is the daughter of a Buddhist Korean mother and Jewish American father. Born in Seoul, she was raised from the age of 5 in her father’s hometown of Tacoma, Wash., where few Jews lived.

Young Angela was blessed with a beautiful alto singing voice, and at the age of 10, was drawn to religion through Jewish music and prayer. She says that when she sang, “I came alive and felt like God heard me.” Fully accepted in her community’s small Reform congregation, she grew up unaware that her religious identity—as the child of a non-Jewish mother—was not recognized by a significant segment of the Jewish world.

Even Reform Jews have taken “one look at my face and questioned how I could possibly be a real Jew,” Buchdahl notes, adding that “the only response I’ve ever found is to continue to do what I do.”

What she does is share—from her synagogue pulpit and now, in a moving memoir—her belief that Judaism has deep spiritual teachings that can be accessible and relevant to all in today’s fractured world through prayer, writings, music and interpreting sacred traditions for modern times.

Beautifully written and steeped in Jewish values, Heart of a Stranger: An Unlikely Rabbi’s Story of Faith, Identity, and Belonging, describes the stumbling blocks she experienced as a mixed-race Jewish girl from a small Pacific Northwestern outpost. It explains how the love of family, deep spiritual faith and determination in “breaking a stained- glass ceiling” of male rabbinic gatekeepers has made Buchdahl one of the best-known and most admired rabbis in America.

She has spoken at White House Hanukkah candlelighting ceremonies held by Presidents Barack Obama in 2014 and Joe Biden in 2023. In 2022, she made national headlines when an armed man seeking the release of a female terrorist in a Texas prison took four hostages at a small synagogue in nearby Colleyville and called Buchdahl as “an influential rabbi” he’d heard of “who had connections,” she writes in the book, to negotiate their release.

In a lighter vein, she was, as she notes in the introduction to her memoir, featured as a clue on Jeopardy! in 2021. The category was “I Am Woman,” and a photo of Buchdahl in a prayer shawl was shown, accompanied by the clue: “Korean-born Angela Buchdahl is the first Asian American to be ordained cantor as well as this leader of a Jewish congregation.”

The question, of course: “What is rabbi?”

Rick Jacobs, president of the Union for Reform Judaism, the movement’s congregational arm, and a former senior rabbi of Westchester Reform Temple in Scarsdale, N.Y., where Buchdahl served as cantor and assistant rabbi for 12 years, observes that she is “the face, literally and figuratively, of 21st-century Jewish life” in a changing American Jewish world.

Across the denominational spectrum, she is aligned with Modern Orthodox Rabbi Adam Mintz in championing conversion work in the Jewish community, often referring potential converts to each other out of a shared belief in strengthening the Jewish future. “Angela is the perfect rabbi” for today, Mintz says, noting that she possesses a commitment to Jewish peoplehood as well as an appeal to a more diverse generation of American Jews.

Jonathan Sarna, a leading scholar of American Jewish history, says Buchdahl “will be seen as an historical figure,” adding: “We’re lucky to have her as a rabbi at this key moment.”

Hadassah Magazine Presents: Heart to Heart With Rabbi Angela Buchdahl

Join us Monday, December 8, 2025, at 8 PM ET for a conversation with Rabbi Angela Buchdahl. She’ll talk with Hadassah Magazine Executive Editor Lisa Hostein about her remarkable journey from South Korea, where she was born, to the rabbinate; finding light and joy in Judaism today amid the many challenges; and her new memoir, Heart of a Stranger: An Unlikely Rabbi’s Story of Faith, Identity, and Belonging.

At a time when Israel has, until recently, been embroiled in its longest and possibly most challenging war following the Hamas attacks of October 7, 2023, when antisemitism is a daily threat to Jews around the world and American society may be more deeply divided than ever, Buchdahl says she is fervently committed to “building up a community of Jewishly educated, joyful and confident” men and women rather than bemoan the very real threats at hand.

Buchdahl has had first-hand knowledge of those threats, based on her January 2022 encounter with the Texas gunman. In one of a series of interviews, she described it to me as “a confrontation with evil” that shook her fundamental belief in humanity and heaven. She said that hearing the man tell her repeatedly on the phone, “ ‘I love death more than you love life’ was “so nihilistic,” she added. She was left “looking down an abyss of darkness” and sought therapy for a time afterward.

“I get angry with God” at times, she says, “and I cry out to God,” wondering how the world could be as chaotic as it is. She says the incident made her realize that “people, including Jews, don’t understand” the power and dangers of antisemitic tropes like “all Jews have influence,” which the gunman said to her. She told her congregants in a sermon the Shabbat after speaking with the gunman that “if you are a Jew in America today and you are not feeling unsettled, you are not paying enough attention.”

Still, “I won’t spend my rabbinate fighting antisemitism,” she told me. “In the end, I don’t think we can get rid of it. It’s been with us for centuries. And I don’t want to use our best talent and resources to fight haters, but to build the strongest Jewish community.”

Close up, it’s clear that the pressures of her public position as well as the praise from congregants and peers have not gone to Buchdahl’s head. Sitting across from me over tea in a midtown Manhattan diner one afternoon, she speaks in soft, even tones about the great satisfaction she has in feeling “divine spark energy” in her work, whether it’s leading a service or having a one-on-one conversation with a congregant in need. “I feel that God is in this,” she says.

Buchdahl is accustomed to being approached by strangers who recognize her, chiefly from Central’s streaming Friday night services. Artfully produced and buoyed by an ensemble of professional musicians, the services became hugely popular during Covid, when in-person events were shut down everywhere.

On the Friday evening in July when I was at Central, I sat next to a middle-aged couple visiting from Los Angeles. The wife said she had been livestreaming the Friday evening services almost every week for five years. “The whole experience is very spiritual for me,” she said, noting with a smile that, given the time difference, Shabbat starts for her at 3 p.m. on Fridays.

The young couple sitting in front of me said they had moved to Manhattan a few months earlier from North Carolina and were attending services in the city for the first time. They, too, had been taken with the virtual Friday evening services and were “looking to connect with our faith,” explained the young man, a Birthright Israel alum.

Within moments, the service starts and Buchdahl and her rabbinic, cantorial and musical colleagues—the synagogue currently employs 13 rabbis and cantors—have everyone wishing each other a Shabbat shalom. Soon, the hundreds of men and women are singing the prayers in Hebrew as they welcome the Sabbath with full voice.

Buchdahl’s path to the rabbinate was far from simple. There were even times when she was ready to give up on Judaism. In her book, she writes how her doubts began at 16, when she had a life-changing experience in Israel that both strengthened and challenged her Jewish identity.

Bright and highly engaged in local Jewish activities in Tacoma, Buchdahl was chosen as one of 25 high school students in the country by the Bronfman Youth Fellowship, a selective summer program in Israel focusing on Jewish learning and Israeli history. (Her aunt had seen an ad for the program in Hadassah Magazine.) During her finalist interview, she learned that traditional Jewish law defines one’s identity through matrilineage. This came as a shock to Buchdahl, given her previous experience of acceptance in her home community. While reaffirming that the Reform movement accepted patrilineal Jews as well, the rabbi who broke the news to her cautioned Buchdahl that “there may be Jews on this trip who do not consider you a Jew.”

Sure enough, it was Buchdahl’s Orthodox roommate on the program who made it clear to her early on that, according to halacha, Buchdahl was not Jewish because her mother is not Jewish. Decades later, she recalls that the encounter—and similar incidents that summer in Israel when she was made aware that others questioned her Jewish status—was “extremely painful and destabilizing.” It was particularly painful because it was during that trip that she fell in love with Jewish learning and text study in a country, she writes, that “felt like a home that had been waiting for me to return.”

She writes poignantly of her ongoing inner struggle as a teenager over her identity, wavering between a deep desire to be a rabbi and the “soul crushing” awareness of being “an outsider” to others. It came to a head several summers later, when Buchdahl was back in Jerusalem on a fellowship to do research for her senior thesis at Yale University on women in the cantorate. Feeling “marginalized and invisible,” she called her mother in tears, ready to stop being a Jew. Her mother’s simple response—“Is it possible?”— stopped her cold. It was only then that she realized that “I couldn’t stop being Jewish any more than I could stop being Korean or stop being a woman. It is wholly who I am.”

Soon after, she made the decision to immerse in the ritual waters of a mikveh, calling it a “reaffirmation ceremony” rather than a conversion, since the Reform movement already identified her as a patrilineal Jew. “It was a way of ritualizing the internal journey I’d been on,” she writes in the memoir.

As a rabbi, Buchdahl sees her primary role to be “a moral and spiritual teacher, not a political pundit, and my inclination is to talk from a spiritual space.” She notes that Central’s clergy “could give a political sermon every week,” but those who attend synagogue “can’t get Shabbat” elsewhere. A common theme in her sermons and in how she conducts herself, she says, particularly important in these binary times, is to seek common ground, to hear two opinions and strive to find a third way.

Given the size and diversity of her congregation and international audience online, Buchdahl knows that she can’t—nor does she want to— please everyone with her views. Her goal, she says, “is to hold a community with strong political and ideological differences and find ways to transcend those differences through song and prayer together.”

Buchdahl has traveled to Israel five times since the October 7 massacre, and she notes that the mood feels different each trip, from the initial shock to ongoing trauma, and from national unity to a fraying over the length and ultimate goals of the war.

She acknowledges that before the ceasefire and hostage release deal in October that saw the return of all the living hostages, she had been “quieter” on the topic of the Israel-Gaza war in the last year, in part because she felt Israelis were still in trauma and she didn’t want criticism, however well-intentioned on her part, to be aligned with Jerusalem’s enemies.

This tension was evident in her Rosh Hashanah sermon this year when she acknowledged at the outset that in the 25 years of her rabbinate, “I’ve never been so afraid to talk about Israel.” She said that if she spoke of her unconditional love of Israel, “some of you will stop listening and decide I’m no longer your rabbi.” And the same would apply among other congregants if she addressed the suffering of Gazans and settler violence in the West Bank.

The war in Gaza is “tearing this community apart” and has been “the most painful experience of my rabbinic life,” Buchdahl said in her sermon. This is a time of deep political divide when “any expression of empathy for the other side is considered threatening or disloyal.” But her message was clear: Citing the holiday’s Torah reading of an angel saving Ishmael, Abraham’s first-born son, from starving in the desert, she asserted that Judaism calls on us to expand our hearts, not harden them. That is “our superpower,” she continued, to “show empathy for all God’s children.”

On October 13, the day when all the living hostages were reunited with their families, she and her fellow clergy sent a message of joy to Central’s community, thanking the Trump administration for keeping the release of the hostages as “an unwavering priority and for reaching this historic ceasefire.” May this “be the beginning of a new story for our beloved Israel, for the Palestinian people and for the region,” the message ended.

Buchdahl will also at times speak out on controversial issues like immigration and racism, sometimes using her personal story to underscore her belief that Jewish peoplehood is a family, not a race. She encourages greater empathy for and engagement with Jews of Color, like her, who make up about 15 percent of American Jewry.

Her memoir, Heart of a Stranger, follows Buchdahl’s clerical career, which began with her 1991 investiture as a cantor and 2001 rabbinic ordination, both from the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in New York. In 2006, she decided to leave the comfort of the suburban congregation of Westchester Reform Temple to become senior cantor at Central. She became senior rabbi in 2014, following the retirement of the much-admired Rabbi Peter Rubinstein, who brought more Jewish ritual and tradition to Central during the nearly three decades he served.

Though Buchdahl has made it to the top of her field, she notes that five decades after the first female rabbi in America was ordained, women are still underrepresented in senior rabbinic positions. She cites a pay gap, a job structure that makes it difficult for working mothers and a subtle double standard that questions whether women have the gravitas to lead a large congregation. “One thing about me,” she says, “is when you tell me I can’t do something, it triggers the survivor/fighter in me to say, ‘Yes I can.’

Buchdahl finds trust and warmth in the deep friendships she has with a small circle of highly accomplished fellow Upper West Side women she describes in a chapter of her book titled “Female Posse.” They, along with their families, serve as “a lifeboat” for her, and have provided a safe space and respite on Shabbat afternoons for more than 15 years. She takes pride in the fact that the friendships include their husbands as well as their children, who have grown up together.

Each of the women in the group I spoke to said Buchdahl brought spirituality into their lives. Ariela Dubler, head of school at the Abraham Joshua Heschel School, calls Buchdahl “a believer who lives and expresses that belief in ways that draw people in.” Ilana Ruskay-Kidd, founder and head of Shefa, a Jewish school for children with language-based disabilities, says Buchdahl is “the hardest working person I know, but she does it quietly, no kvetching,” attributing that quality to “the Buddhist, non-complaining part of her.”

Buchdahl, in her memoir, describes her close friend, author Abigail Pogrebin, as her “book doula, master editor and lifelong chavruta” (study partner). Pogrebin says that when she first heard Buchdahl sing at a bat mitzvah at Central in 2006, “I felt in her presence that God had entered the room.” Almost immediately, she convinced her husband that they should become members of Central.

“I saw that Angela was building a worship experience for what people need,” says Pogrebin, who served as president of Central for three years, starting in 2015.

A notable element of Buchdahl’s memoir is that it manages to offer a universal message through the lens of Jewish wisdom. Each chapter of the book describes a piece of Buchdahl’s life and is followed by a brief d’var Torah whose theme connects the two. For example, a chapter dealing with Buchdahl’s dilemma in balancing her manifold obligations as senior rabbi of Central with allotting quality time for her husband, Jacob, an attorney, and their three children, Gabriel, 25, Eli, 23, and Rose, 20, is followed by her observations on tisomet lev, Hebrew for “attention.”

Buchdahl writes that a range of new technologies have “made our flexibility a priority over our focus… We have lost our ability—maybe even our will—to give anything everything.” She notes that “attention is perhaps our highest form of care, excellence and love. Our most precious commodity. The Hebrew word for attention, tisomet lev, literally means to ‘place your heart.’ When you give something your full regard, you direct not just your eyes, ears or mind but also your heart…. Ultimately, our lives will be the sum of what we’ve given our attention.”

Buchdahl says she wrote her memoir with a wide audience in mind. A meditation enthusiast, she suggests that “maybe having a Buddhist mother, I am translating Judaism through multiple lenses to make it accessible.”

She also notes in the book that the core values of her rabbinate are grounded in her, and her mother’s, experience as immigrants, and their struggle for wider acceptance while clinging to a steadfast belief in each person’s unique place in the world—and the responsibility to improve it.

During her late teen years, Buchdahl writes, she never felt “fully Jewish,” always the outsider. But over time, she began to embrace her multiracial heritage and identified with the biblical “mixed multitudes” who traveled from Egypt with Moses and the Israelites in the desert in search of freedom and a spiritual path.

She came to recognize that everyone feels like an outsider in some way, as she notes in her book: “Feeling like a stranger might be the most Jewish thing about me.”

Gary Rosenblatt, a Pulitzer Prize finalist, was editor and publisher of The Jewish Week of New York from 1993 to 2019. Prior to that, he was editor of the Baltimore Jewish Times. He writes a column, “Between The Lines,” on Substack.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Rochelle Miller says

I am deeply moved by this beautiful voice who is able to speak so beautifully about her past, with challenges that she overcame with time. She has motivated me to believe and practice Judaism wherever I am! I felt Rabbi’s history and past and future to be one that many share, and her positivity is felt with love and appreciation. Thank you Rabbi Buchtol for your inspiration.

Jacob A Saltzman says

This “Rabbi” should stick to religion, enlightening, inspiring, motivating Jews to prayer and traditional practices. She should keep her politics to herself and off the lecturn..She is not Jewish and cannot ever know the real challenge Israel has with its 9 million population against the family of Ishmael with its 2 billion population that only wants to see the destruction of Issacs family.

Barbara Shapiro says

Mr Saltzman-

I find your remark like Wendy Reiner stated despicable. Rabbi without the quotes IS a fully fledged Rabbi and she does keep her politics to herself. Rabbi Buchdahl had a formal conversion to Judaism when she was 21; maybe in part because of people like you who believe she isn’t Jewish. I heard her speak the other night and she stated this. Perhaps you feel that Orthodox Jews that convert are not “real” Jews? She is as Jewish as you are and surely more compassionate with a congregation that adores her. She stated in her lecture the other night that she feels Rabbi’s and all Clergy should not endorse candidates or get involved in Politics. Where were you when all these people before the NY election were complaining she didn’t sign the 1000 Rabbi letter about Mamdani? She didn’t sign it because she wanted to stay out of the arena of politics. What good does it do to write something like you did? I was born to two Jewish parents and Rabbi Buchdahl is much more “Jewish” than I am and no one not even you can take her Jewishness away.

Wendy Reiner says

After reading your thoughts/dictate I can feel your hatred toward those who do not fulfill your high and mighty mold of who is Jewish and who is not. It makes me sad that in these times you have not seen the beauty of the Jewish peoples mosaic who truly seek a peaceful existence and close relationship with God. I guess for you being a Jew is under your terms. I do not know you. You must have known Rabbi Benjamin Brilliant at Pelham Parkway Jewish Center in the Bronx. In the 50s and 60s A conservative temple with an orthodox Rabbi

At the age of 5, I came to the realization that he was a bigoted, hateful nasty person.Never entertaining any discussion unless his voice led the way. You sound a lot like him. Judaism is a beautiful religion and many cultures have found a spiritual home. I had to live with his cruel and unhealthy thoughts for 11 years.

Everyone has their challenges, we learn, we grow, we try to be the best we can. Your attack on Rabbi Buchdahl is meanspirited and certainly not constructive. If that’s what you think it is your first amendment right to say such. Her sermons are well thought out and quite constructive. Each creating a y backdrop to continue conversations and create opportunities for discourse. The comments/opinions are mine. And mine alone. I was compelled to write because your verbage is the antithesis of who she is, from my respective.

Wendy says

Please not I was replying to Mr. Saltzman’s comments

Nina Sabghir says

Wendy, thank you for your thoughtful response to Jacob Saltzman. I too am perturbed by his rigid and insensitive comments. You are far more civilized and articulate than I could have been. I have a son in law whose own grandmother was from Seoul S. Korea. She underwent an Orthodox conversion. Her children and grandchildren have integrated Korean culture with Torah observant Judaism.

I have daughter who married a Puerto Rican. My granddaughter inherited her father’s looks and her mother’s Jewish identity. There’s room at the table for all of us. As a tiny nation, we need to maintain achdus, togetherness, even when we don’t always see eye to ete.