Arts

The Mom Who Co-Designed Israel’s Supreme Court Building

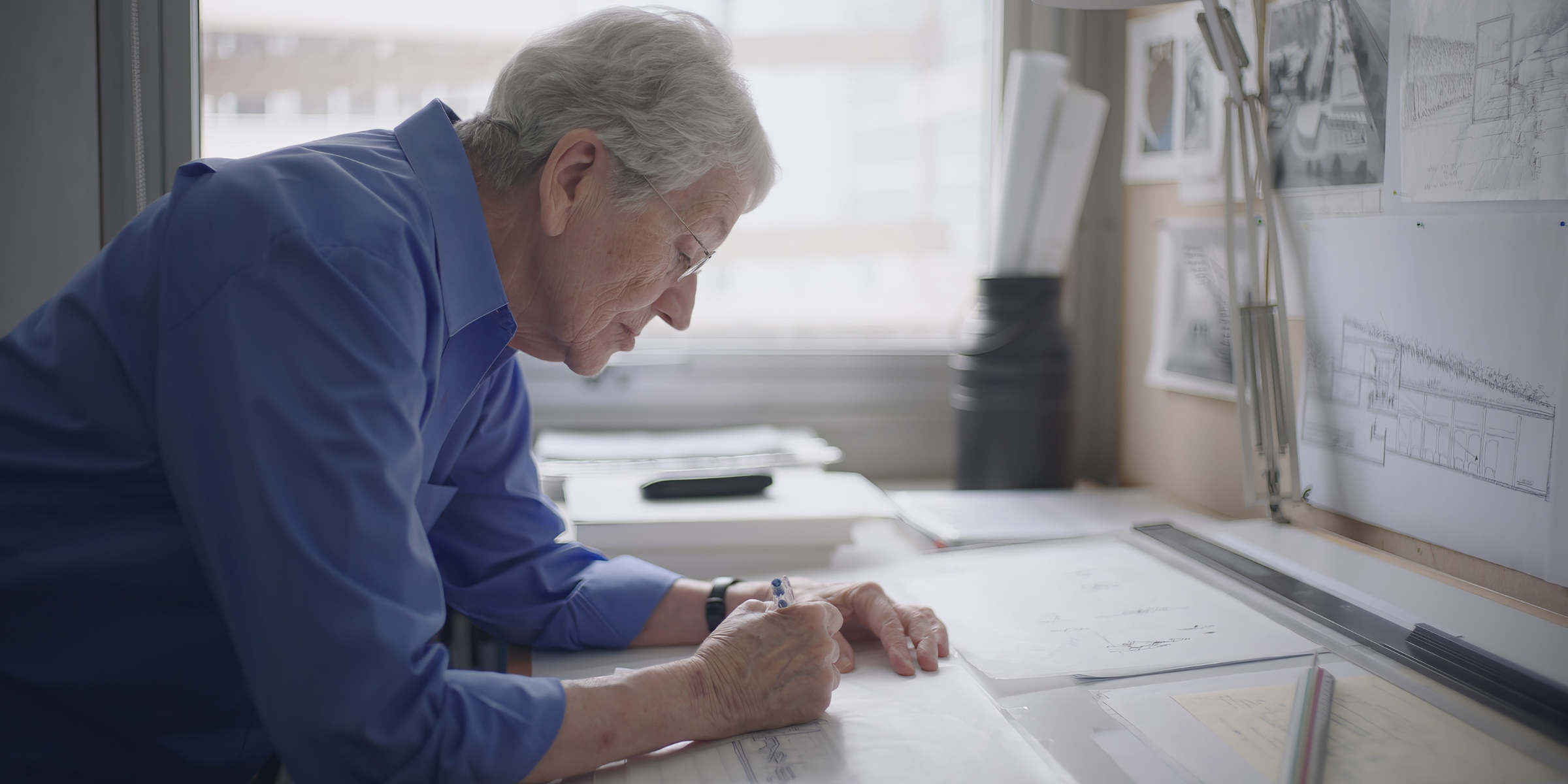

Ada Karmi-Melamede is considered one of Israel’s most celebrated architects. Over the past four decades, the 88-year-old Israel Prize recipient has designed some of the nation’s most iconic public buildings, perhaps none more so than the Supreme Court building in Jerusalem, which she conceived of with her late brother, Ram Karmi. She is also responsible for designing the Open University of Israel campus in Ra’anana and the Ramat Hanadiv Visiting Center in Zikhron Ya’akov as well as many commercial and residential buildings.

Ada: My Mother the Architect is a loving, informative and revelatory documentary from her daughter, Yael Melamede, a filmmaker, who shares insights in both Hebrew and English sourced from her incredible life and prolific career. Along the way, Karmi-Melamede offers a mini-course on architecture and the creative process that may change the way viewers see buildings. The documentary is being shown at Jewish film festival throughout the country, including at the Jewish Women in Film Festival on November 1 to 4 at the Tribeca Synagogue in New York City.

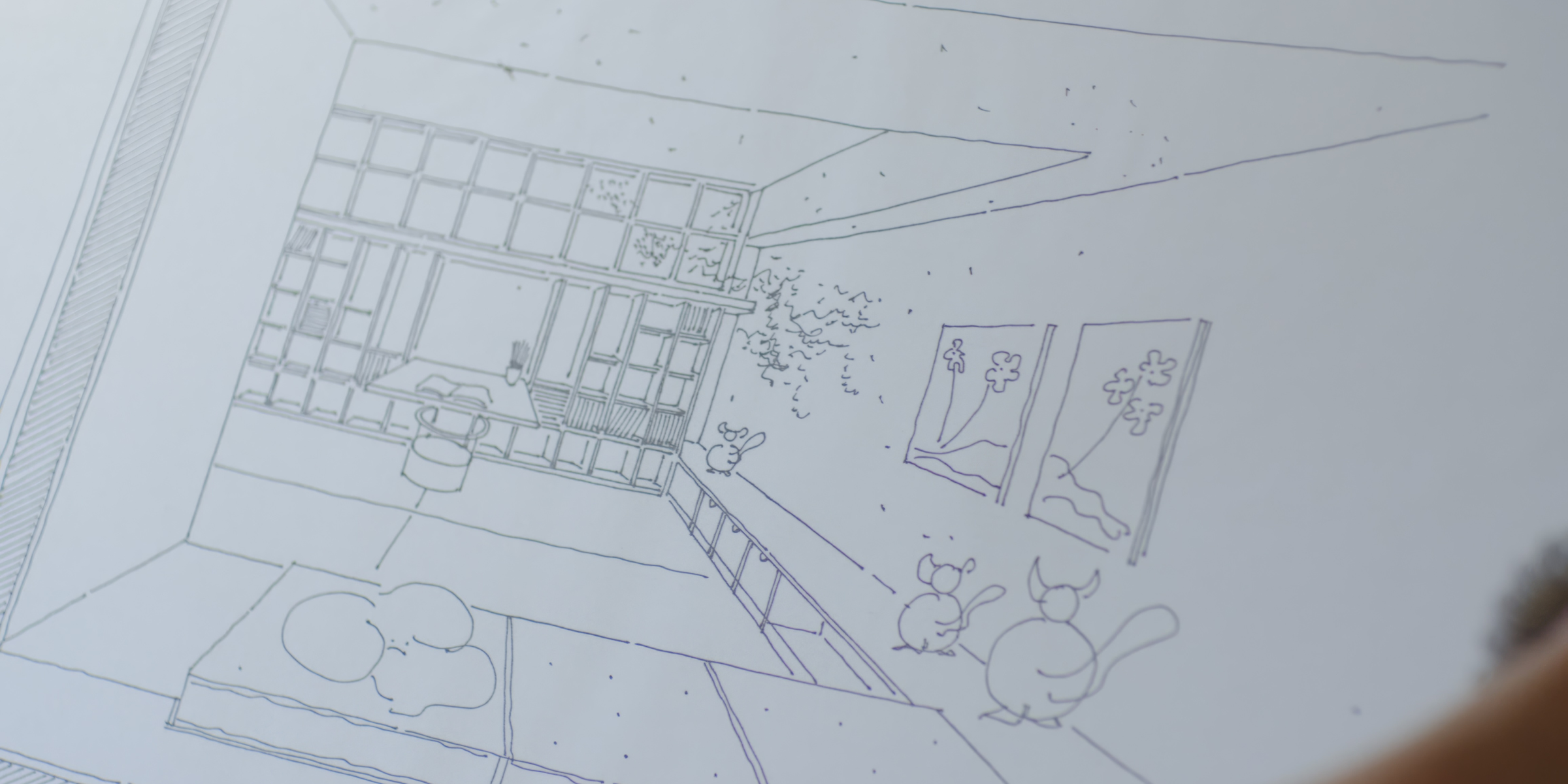

At the heart of her philosophy is that buildings need roots—a connection to the ground on which they stand. That may sound strange until you consider that in Israel almost every plot of land has a story. Indeed, her buildings and public projects curve and work around the landscapes into which they are set.

Another facet of Karmi-Melamede’s aesthetic involves the placement of windows and sky lights to manipulate light. It’s often subtle, best noticed when you stand in place for a while and watch beams of light move as the sun shifts overhead.

But it can also be powerful. Walking up the stairs of the Supreme Court building you reach a landing that features a glass wall through which all Jerusalem is unfurled. It is breathtaking, even when shown on film.

“Every single time I go to the Supreme Court, and I look at Jerusalem at the top of the stairs, I get emotional. I even get tears in my eyes sometimes,” Aharon Barak, former chief justice of the Supreme Court, says in the documentary.

The film also explores Karmi-Melamede’s background. She was born in Mandatory Palestine a decade before the declaration of the state. In addition to her brother, her father, Dov, was also an architect. She studied architecture in London and married businessman Amos Melamede. The couple moved to New York, where their three children were born. She worked in the field and taught at Columbia University between 1969 and 1982, but ultimately was denied tenure, most likely, her daughter implies, because she was a woman.

That rejection, Yael Melamede, herself trained as an architect before she went into film, said in an interview with Hadassah Magazine was “a catalyst for what she did, for doing something different and taking a risk, because she was angry. Because she was offended. Because she wanted to practice.”

To practice her craft was the reason Karmi-Melamede moved back to Israel in 1986. She needed to be in the country to work with her brother on an international competition to design the Supreme Court—a competition that they won. Her husband and their three children, however, remained in the United States, though she would periodically visit. Melamede, the youngest of the three, was 14 when her mother moved.

That move is an undercurrent that runs throughout the film, surfacing first in the opening minutes when Ada asks her daughter, “What do you want?”

Melamede replies, “I want everyone to know you love me.”

In a lengthy telephone interview, Melamede spoke to Hadassah Magazine about architecture, filmmaking and her relationship with her mother. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Was creating the film therapeutic?

I would say it was. It was interesting for me. I think I learned things about my mother that I didn’t expect. But really it was more an exploration of how to tell others about her work in a way that would be interesting to people who didn’t know her.

Did the project provide you a new perspective or understanding?

I think a lot of people assume I have a complicated relationship with my mother, but I really don’t. I think we have a beautiful relationship, a very warm and loving one. I have absolutely no resentment about my mother’s choices. I think in every case she made the right one, and I agree with the choices she made. I just think that they came at a great cost, but I think the cost to her and me was worth it.

Can you describe that cost?

Ada was so focused on her work and living so far away from her nuclear family that she missed out on a lot—from spontaneous gatherings like brunches and dinners, to events like birthdays and graduations, to bigger things like being able to spend meaningful time with her grandchildren.

You’re very understanding.

I think if my mother’s story was that of a father, people would think he was the most amazing parent. They wouldn’t question his choices, even though he’d also be very far away. With women, we are more judgmental. Growing up, I really believe she made the right choices. But I also think along the way we didn’t understand the cost. And looking back I think there were many things that she missed out on that were hard for her and for us.

You were a teenager when she left. Can you tell us about it?

It’s weird. She didn’t leave all at once. It wasn’t like she packed her bags and went. It was a gradual thing. She just started spending more time in Israel. Ada and Ram were invited to the competition [to design the Supreme Court building], so she stayed a little longer. When they won the competition, she was there full-time. That’s why it never felt sudden. It felt like, “Oh, she’s just spending more time there. Oh, she has work. Oh, she’s got to be there for this building,” and then her career took off and that was kind of that.

You clearly had the architecture gene. Why did you give it up?

I never found my way in the profession. I didn’t find my language of expression or my way of feeling at ease.

Have you found similarities between your work as an architect and your vision as a filmmaker?

They’re so related. Filmmaking is telling a story, too, and making a building is telling a story in three dimensions. I think the skills needed to navigate both are similar. You’re so reliant on so many people. You know you can design the most amazing building in the world, but other people have to build it. You’re reliant on them and reliant on the materials being just right. It’s the same with film, where you work with a cinematographer and hope they’re channeling what’s important to you. And with graphic designers and musicians. Architecture and film are both team sports.

In the wake of October 7, there have been suggestions that there is a soft boycott of Jewish and Israeli documentaries, including this one. How has that impacted Ada?

It’s a very tough market for independent film in general and much harder for films having anything to do with Israel. I believe this comes from a general desire to avoid controversy as well as any anti-Israel sentiment. Along with that, independent documentaries are not selling regardless of whether they’re Israeli or Jewish films…. The larger issue is the fact that the bottom has fallen out of the documentary marketplace, creating a perfect storm for films with Israeli subject matter that face an even greater challenge in the marketplace.

What was your mother’s reaction to watching the film?

The first time my mother saw the film, which was basically when it was finished, she paused for a moment and then looked at me in disbelief and said, “I can’t believe it’s not boring.”

Curt Schleier, a freelance writer, teaches business writing to corporate executives.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply