Arts

‘Mere Things’ Bears the Weight of Jewish Memory

In the opening section of his 1926 epic poem “Paterson,” William Carlos Williams lays down a marker, a revolutionary credo, for his generation of American poets: “Say it, no ideas but in things.”

It’s a mantra that seems to animate the work of Israeli photographer and collage artist Ilit Azoulay, whose just-opened show at The Jewish Museum in New York City—her first solo exhibition in the United States—bears the unassuming but sly name, “Mere Things.” The works on display, of course, are not “mere things”; they bear the weight of Jewish memory.

As a creator of photo montages, Azoulay, who is a graduate of the prestigious Bezalel Academy of Design in Jerusalem and whose works have appeared at the Venice Biennale and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, is a collector and re-assembler of “things.” To create her works, she rummages around for months in the often-dusty archives and back rooms of the repositories of Jewish history—venues like The Jewish Museum and the Israel Museum in Jerusalem—in search of objects she will photograph and then replant, so to speak, in modern times, giving them new life.

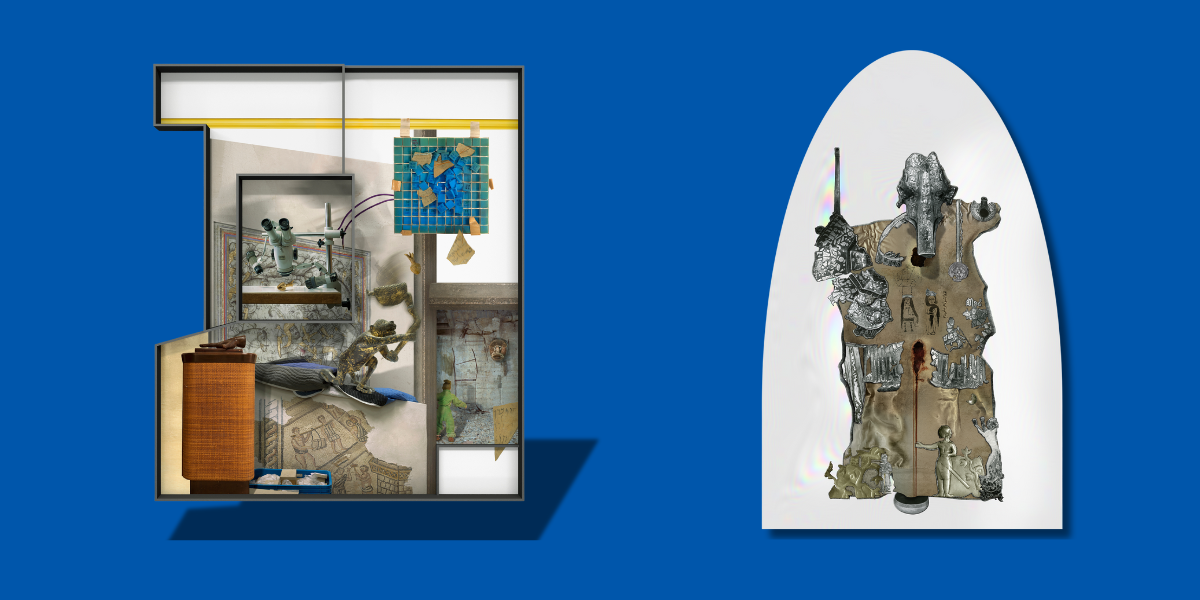

In “Mere Things,” which features large-scale work from previous exhibits as well as a new piece created for The Jewish Museum, the past and present are on a collision course. Azoulay digitally stitches together separate photos of objects into one image, sometimes in jarring ways that unmoor them from their original context, and places them in what look like enclosed frames, creating images that are akin to Persian miniatures.

“It’s like Ilit is digging back into history,” said James S. Snyder, The Jewish Museum’s director, who previously led the Israel Museum when it commissioned Azoulay to create an earlier series that included some of the works seen in “Mere Things.”

Take the cultural mashup of objects in Vitrine No. 9: The return of things that are no more, from 2017, which uses images of some of the artifacts she found in the Israel Museum. On the top half of the work, there is a collection of colorful images that includes a yellowing map, an ornate copper chandelier, fragments of pottery, what looks like a Torah crown and an Indonesian puppet holding a squiggly walking stick. The bottom half of the image centers on a metal sculpture of a hulking prehistoric animal atop what could be a maroon ceremonial shawl set against a gold-leaf background. The whole piece is enclosed in a frame, focusing attention on the juxtaposition of the various elements.

“She spent three years at the museum,” Snyder said, “exploring the physical foundation but also the storage rooms, the basement, the underground pathways. And she also interviewed a lot of staff members. The work was about the objects, but also about the memories and reflections of staff members.… It was about the ideological archeology of the museum, and then…the objects and artifacts, many of which have been overlooked for decades.”

“It’s the notion,” Snyder continued, noting the guiding principle behind Azoulay’s body of work, “of all things connecting across time and cultures”—even to the present moment.

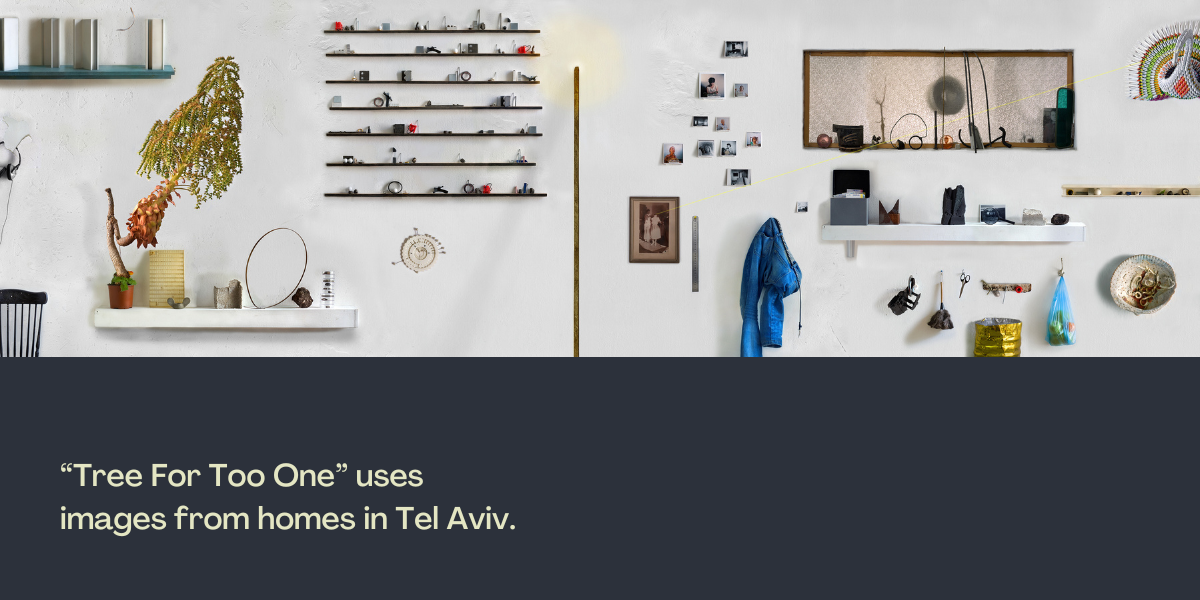

The show at The Jewish Museum spans 15 years of Azoulay’s career, much of it revealing an artist and archivist at the intersection of urban preservation and photography. In 2010’s Tree for Too One, she uses discarded items found in soon-to-be demolished homes in south Tel Aviv—a rusted bolt, a pair of jeans, a bright red toy—and in 2014’s Shifting Degrees of Uncertainty, over 85 individually framed prints with items photographed from cities around Germany. (She currently lives in Berlin.)

And in Queendom, originally part of the Israel Pavilion at the 2022 Venice Biennale, Azoulay creates another kind of reconstruction. For the work, which reuses the photo archives of David Storm Rice, a largely forgotten Austrian British and Jewish scholar of Islamic metal vessels, she challenges the male-dominated mythological stories he found in Islamic medieval art. She digitally manipulated his photographs of the inlaid metalworks, creating a photomontage with new feminine forms and shapes that imagine a matriarchal society.

Azoulay, whose parents moved to Israel from Marrakesh, Morocco, in the 1940s and ’50s, appears to have the artistic urge to archive and document in her DNA. Her family owns a music store in the Israeli port city of Jaffa, and she grew up listening to a wide range of Middle Eastern music. The shop, she told ArtReview magazine in 2022, holds “an archive of vocal artists from all over the region. I saw my father and his brothers through the years recording and archiving more and more voices from the Middle East, creating a net of connected cultural histories, based on the natural understanding of being part of the region.”

The new work in the exhibition, Unity Totem, drawn from objects in The Jewish Museum’s collection, seems inspired by her upbringing in Jaffa as a child of Moroccan immigrants. While there are some items from European Jewry, most of the objects in the fanciful photo collage can be traced to the Arab world, including images of Torah finials from 19th-century Tunisia and Yemen, a Torah pointer and Hanukkah lamp from Morocco and a green velvet pointed woman’s hat from Algeria.

The 19 pieces of Judaica appear suspended in Unity Totem, as if they were floating free or, perhaps, had just blown in from what could be an open window pictured at the right of the piece, near the frame. Look closely, though, and the objects are tethered to thin strings that emanate from the green felt hat, atop which rests a Tunisian Torah finial and an unrolled Scroll of Esther from the Ottoman Empire. The overall image brings to mind a circus carousel, with the green hat as the point of the big top. A puff of smoke (ritual incense?) appears to waft out from under the hat toward the direction of the window, covering a number of the objects with a cloud-like haze, a sacred spirit moving over them.

In Unity Totem, Azoulay is creating her own net of connected cultural histories, binding an 18th-century shofar from Europe to an amulet necklace from late 19th or early 20th-century Kurdistan to a Torah crown in the shape of Venetian headgear from Italy.

In a way, there is a touch of magic, an aesthetic sleight of hand, in what Azoulay pulls off in Unity Totem. The 19 objects are, of course, separate and discrete—mere things, if you like. But in the collage, they are braided together under the big top of Jewish history, dancing free but held in a tender embrace by the spidery web to which they cling.

“Ilit Azoulay: Mere Things” runs through January 5, 2025, at The Jewish Museum, 92nd Street and Fifth Avenue in New York City.

Robert Goldblum is a writer living in New York City.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply